Ursine wars: alpine imaginaries and animal genealogies in the Trentino region

In the depth of the Trentino mountains, there is a high-security prison. Amongst the captives is M49, a brown bear classified as dangerous for his reoccurring attacks on livestock and human property. The animal has been the subject of much media attention, both in his homeland and abroad. What are the cultural values that lie behind the contestation of this figure? Where does the image of the malicious bear come from and how has it evolved? In this article, Amedeo Policante explores the different paths of this genealogy, showing how they still feed into contemporary culture today.

On the 18th October 2020, hundreds of people marched through the city of Trento in protest against the living conditions of inmates held at the Forestry Nursery Centre “Casteller”: a complex consisting of a two-by-six-metre cage surrounded by three seven-thousand-volt electric fences, a four-metre-high barrier, dozens of CCTV cameras and an operations centre manned by armed guards in green uniforms. From the outside, it looks like a maximum-security prison. The inmates do not have ordinary names, but unique identification codes that encapsulate a variety of genealogical information about the subject: codes such as M57, DJ3, and M49.

‘We’ll dismantle the Cage. On the side of the rebellious bears’, this is the slogan that accompanies the activist movement instigated by the Bruno Social Centre and Anti-speciesism Assembly on October 18, 2020. Photo credit: Bruno Stivicevic.

M57 is a young male, identified as the probable assailant of a policeman near Lake Andalo. Today, according to a recent police report presented to the Minister of the Environment, “he constantly repeats movements in a rhythmic manner” and self-inflicts “skin lesions in his left forearm”. DJ3 is a seventeen-year-old female who was responsible for “numerous incursions into built-up areas” and “predations on sheep”, before her final capture over nine years ago. Now, “she is in hiding and avoids all contact.” M49 is an internationally renown character and, at least according to an official statement from the province of Trento, is a “highly harmful” individual. He is considered guilty of “preying on cattle, horses, sheep, goats, pigs and poultry”, and charged for multiple “attempts to break into dairies and alpine stables”. He has already escaped twice from the Casteller structure, tearing down the iron bars and then seeking shelter in the Lagorai woods. Today: “He has stopped feeding and expends all his energy against the shutter of the enclosure”.1

The Casteller Centre for the rescue of alpine fauna: “a true place of peace for injured animals”2 and “a Dante-esque circle of hell, where the imprisoned animals are daily bombarded with psychoactives, locked in cages of a few square meters in conditions of intense psycho-physical stress”.3

The three inmates have been judged by the authorities as “problematic subjects”, a technical term used to indicate individuals considered dangerous, or simply an excessive burden on the local economy. All three are bears, born in Trentino, the sons and daughters of bears imported from Slovenia between 1999 and 2001 in order to replenish a local population on the verge of extinction.4

The protesters, demanding freedom for the bears, parade through the streets of Trento, accompanied by protest banners and ursine iconography. They reach the urban outskirts, where the iron and reinforced concrete cages are located. They knock down over seventy meters of the outer fence. They come into conflict with police officers in riot gear. The absurdity of the situation attracts swarms of photographers to the scene of the clashes. Hundreds of images of bears and men are produced in those hours and, the following day, they fill the pages of local and national newspapers. The event provokes haunting questions that find hasty answers in village cafés, town bars and family dinners. How did we get here? Where does this political conflict come from? Who fights on the fringes of a forest centre, and why do armed police guards defend its perimeter? Also, who are these plantigrades? What do they represent to the women and men who fight in their name and tear down their cages? And to all the others who put them in those cages, and who now protect the steel bars?

The name of the Centro Sociale Bruno in Trento commemorates a bear cub born in Trentino in 2003. Three years later it was shot and stuffed in Germany following an illegal trespass.5

This article starts from the premise that, if we really want to better understand the images produced by the Casteller revolt, it is necessary to take several steps back. Alpine mountains and valleys have, for centuries, been the scene of frequent encounters (and clashes) between homo sapiens and ursus arctos – encounters which, as we shall see, have shaped the various forms of Alpine culture and society over the centuries. Tracing the history of this difficult interspecies coexistence cannot, therefore, be understood as a purely museological and archaeological exercise. Taking a step back is always a strategic manoeuvre – a political act that determines the angle and perspective from which we view our present.

A small example, paradigmatic in its everyday banality may be a sufficient starting point. In the days immediately preceding the Casteller uprising, one of the main British newspapers published a long article entitled “Papillon the bear: how the ‘escape genius’ sparked a national debate in Italy”. The article includes an interview with Mauro Varesco, an entrepreneur from Val di Fiemme, who advocates the reinstatement of bear hunting. “In these parts,” explains Varesco, “until a few decades ago, people were incentivised with large bounties to hunt bears. Our ancestors got it right”.6 In this scarcely sketched, but extremely popular, narrative (since it has been endlessly repeated by the Northern League Presidency of the Autonomous Province of Trento), the current zoological-political clash involves two distinct and radically opposed fronts. On the one hand, a population forged by centuries of struggle against bears, devoted to liberating the mountains from the uncomfortable presence of the plantigrade; on the other, a modern, urban environmentalism, tied to a sensibility that is totally foreign to these valleys.

But is it really all that simple?

“To rid ourselves of this animal infestation”: A preliminary Genealogy of Human-Bear Relations in the Trentino Region

Three volumes, published relatively recently, allow us to better reconstruct the historical-semiotic process through which the image of the alpine bear changed over time, particularly, from the early Middle Ages to the present day.

Men and bears in the hagiographic sources of the early Middle Ages (1988) by Massimo Montanari convincingly shows a definite correlation between changing material socio-economic conditions and shifting cultural representations of the wilderness. In particular, the book traces the gradual process of anthropomorphisation that characterises the Alpine mountain environment between the early and late Middle Ages, and the way in which this progressive colonisation of mountain space contributed to a transformation of human-animal relations. The progression of the agricultural economy corresponds, on a psychological level, with a new image of the mountain: once an inaccessible space of anti-civilization, the mountain becomes an attractive empty space that may be transformed, cultivated and potentially valorised.

“In an economic and cultural context that is shifting towards agriculture and the domestication of animals,” Montanari writes, “the figure and narrative role of the bear, the image of the wildness, are changing. The encounter between bear and man no longer takes place inside the forest, but outside it, generally at its margins. The man (in our sources, the saint) does not seek, but is rather subjected to that encounter, he lives it as a menace emanating from the outside.”7

In other words, precisely because the mountain leaves the wilderness to enter history, the bear progressively appears as an uncomfortable animal, a symbol of everything within nature that resists and rejects the civilising action of man, and that must, therefore, be continually reduced to reason. The relationship with the bear, according to Montanari, ceases to be “somehow equal, based on mutual recognition and possible coexistence – to become a Tierkampf, a battle with the beast”.8

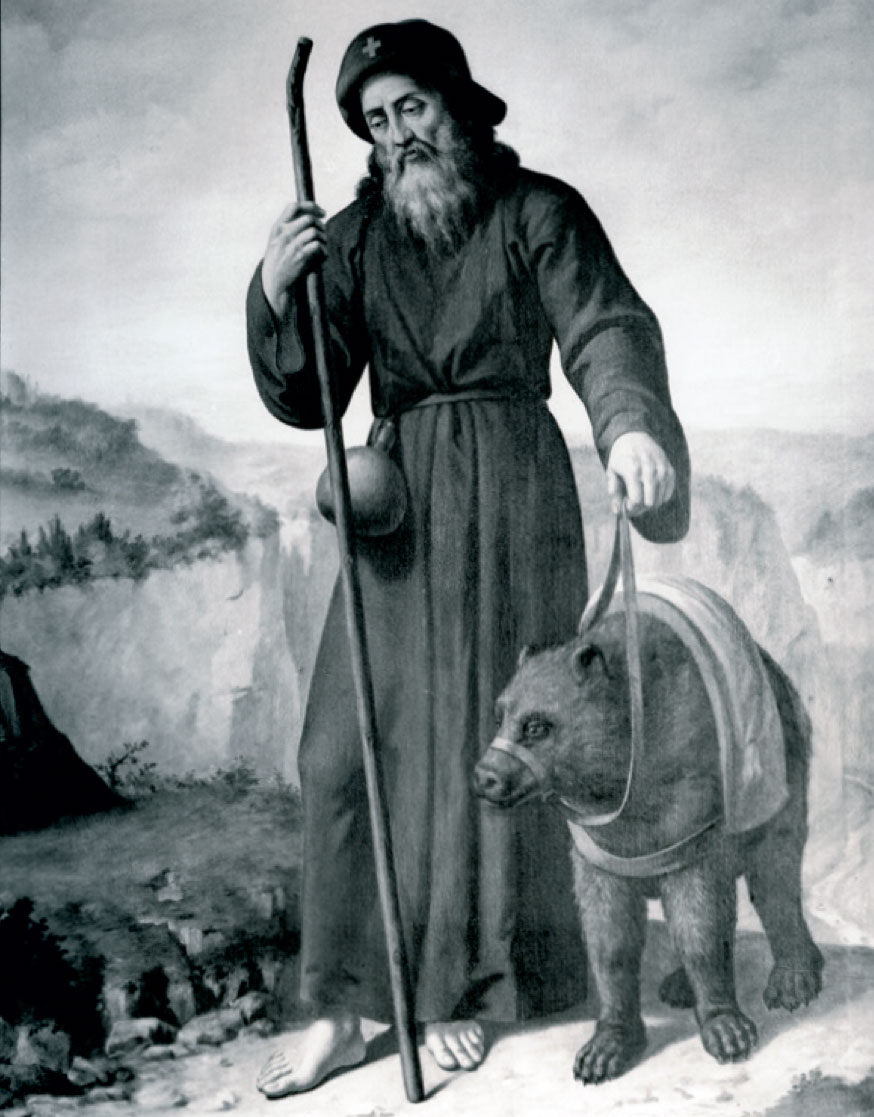

“An amazing fact, or strange thing! The bear, the beast, becomes human. Amazement greater than when man turns into beast ”. This inscription, written by an unknown author on the entrance portal to the sanctuary of San Romedio in Val di Non, recalls the most famous miracle attributed to the Hermit Saint: having ridden to the city of Trento on the back of a bear tamed for the occasion.

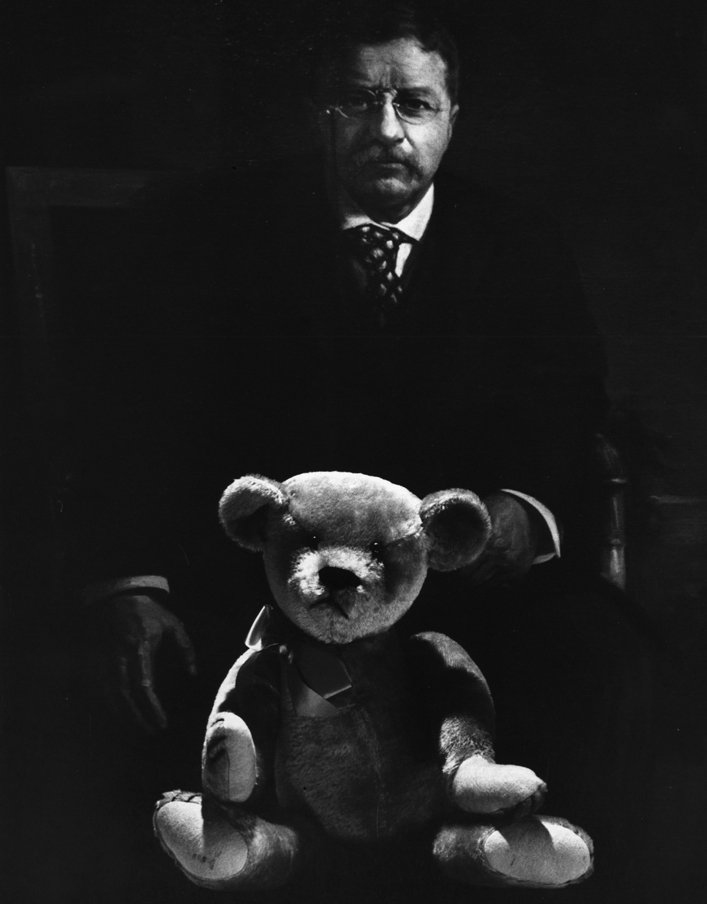

In 1902 Teddy Roosevelt, then President of the United States, refused to shoot a cornered bear cub during a hunting trip. The event was widely reported and inspired the ‘Ideal Novelty and Toy Corporation’ to produce the first Teddy Bear: a symbol of a tamed and fragile nature.9 Paradoxically, in the very moment in which the bear (as a living species) recedes in the background and disappears from lived experience, the bear (as stuffed cultural icon) becomes ubiquitous. Photo credit: Nina Leen.

The number of records pertaining to the bear’s subjugation to the dominion of man is vast, and is echoed in new, varied and surprising iconographic examples. According to Anna Benvenuti, who develops and broadens the foundational studies of Franco Cardini (1986), Giorgio Massola (2013) and Michel Pastoureau (2008), “in most of the cases represented by the hagiographers, the animal – after having attacked and killed the beasts of burden used by the saint in his travels – is forced to replace them until, after the punishment, he is allowed to return to the feral disorder of the wasteland. These images of shepherd bears – hitched to wagons or transformed into mounts, devitalised from any ferocity or belligerent mimesis, devoid of the alien allure of the deep, uninhabited forest – are iconic of a new cultural attitude toward the environment”.10

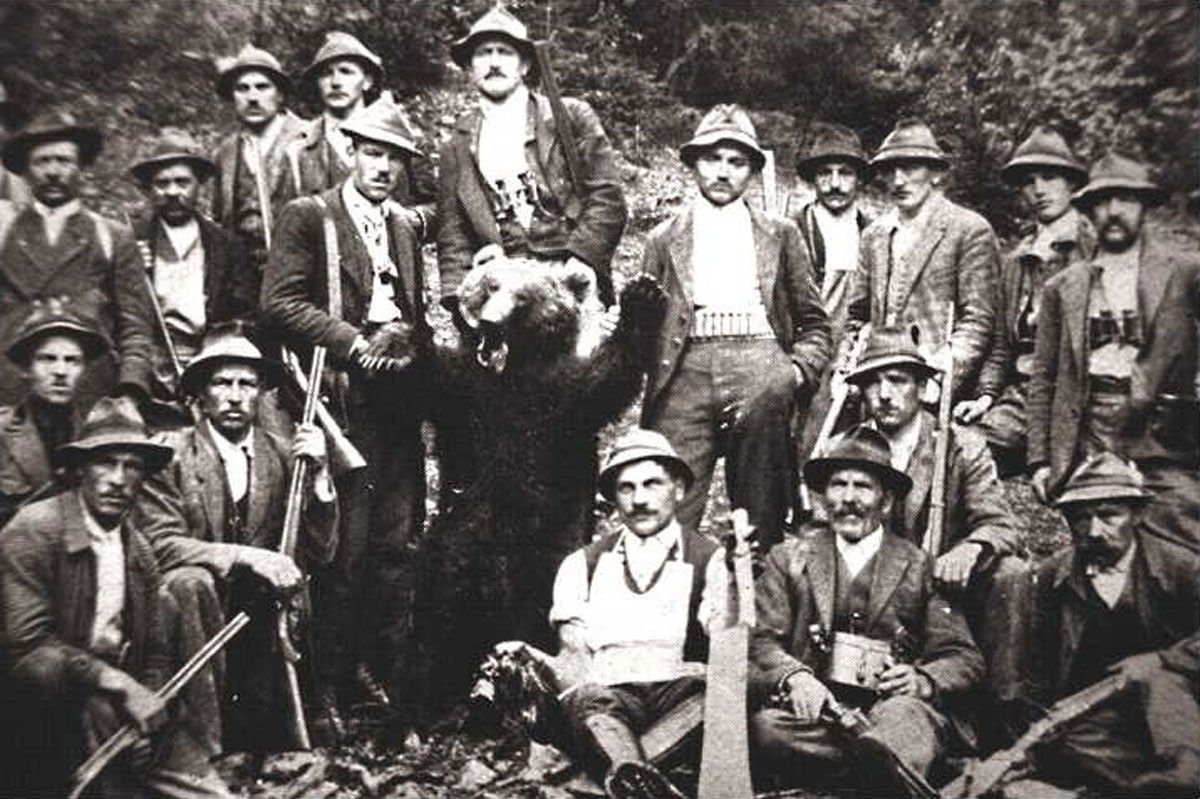

This cultural devaluation of the bear continued throughout the following centuries, reaching its peak in the systematic and state-approved hunting that, between the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, led to an irreversible decline of the population of alpine bears. This bloody history is the focus of Sulla Pelle dell’Orso: la caccia nei documenti del passato e nelle memorie ottocentesche di Luigi Fantoma (On the Skin of the Bear: Hunting in the Documents of the Past and in Luigi Fantoma’s Memoirs of the Nineteenth Century), an important study by Trentino historians Anna Finocchi and Danilo Mussi. The volume revisits – through valuable archival work – the documentary record of an extermination that was announced, planned and scientifically pursued.

The pivotal date of this story is October 18, 1818, the day in which the Austro-Hungarian government – which until 1918 governed the entire Eastern Alps – declared a “war on bears”. Bounties, incentives and awards were introduced – to which sometimes were added further prizes instituted by various local administrations – in order to encourage all mountain villages to engage in a systematic extermination of the bears still present in the Alps. For the institutions, bears were now considered primarily an obstacle to the economic growth of Alpine regions. Their extinction became an explicit political goal: not an unpleasant historical accident, but an integral part of the ongoing modernisation process.11

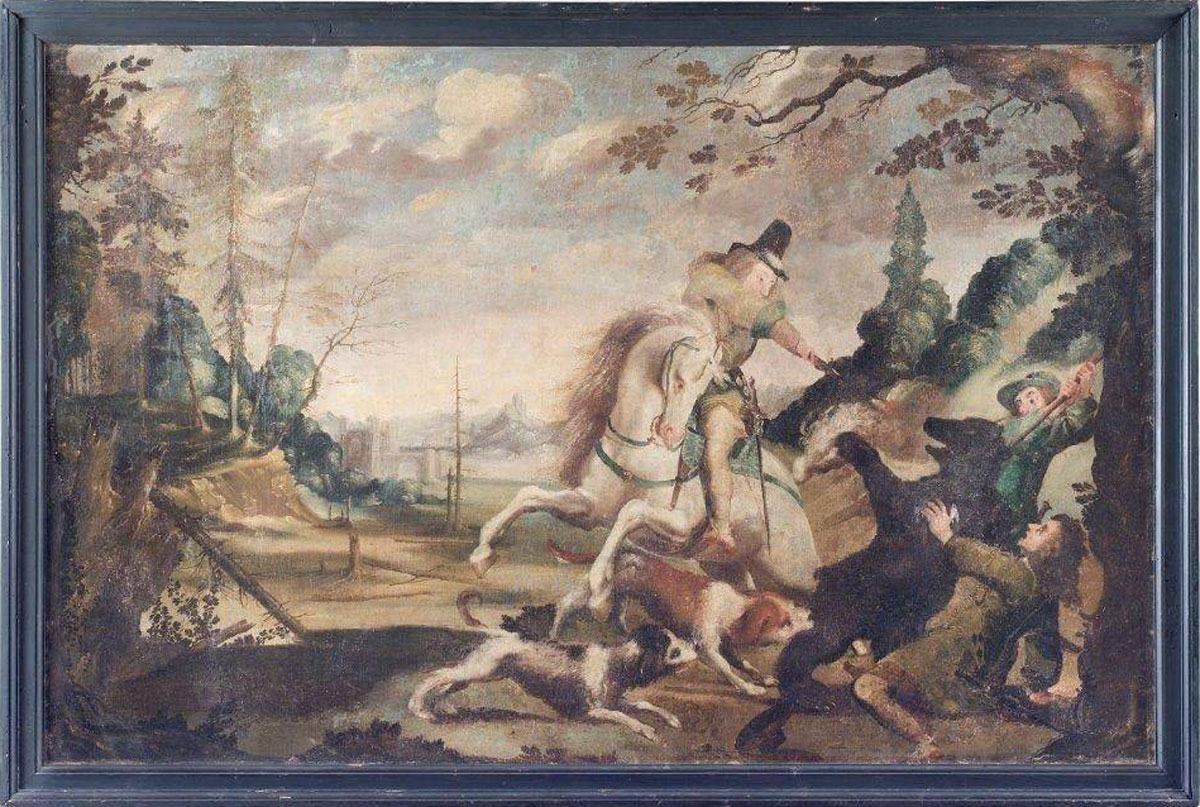

Bear hunting – which throughout the Middle Ages and the early modern period was still an epic, dangerous and expensive business – was progressively democratised and simplified by the diffusion of efficient and cheap firearms. The first professionals ‘bear hunters’ made their way into the scene: people of modest background, such as Domenico Ramponi and Luigi Fantoma, who built their economic fortunes on the serial collection of bounties.

“Bear Hunt” by Stephan Kessler (1678), long-time resident in Bressanone. Until the early 1800s, bear hunting remained an epic and aristocratic undertaking, a small war, fraught with considerable risks and frightening costs. In this oil on canvas, an elegantly dressed man uses a musket, a white horse, two chariots, and two pages with spears attempting to bring down a bear.

The war, however, was not only fought in the valleys and in the woods, but also in university classrooms and urban cafès, leaving conspicuous traces in institutional documents and local memorabilia. Prominent examples of this modernist sensibility may found in the writings of classic scholars such as Giovanni Battista Sicheri, for whom the bear represents a “cowardly wound”, an “infesting animal” and an “evil beast”;12 as well as in the reports of a naturalist such as Agostino Bonomi. Born in Madice di Bleggio in 1850, member of the Accademia degli Agiati of Rovereto and several times consultant of the Provincial Council of Trento, Bonomi wrote about a valley in Trentino in 1889: “Among so many beautiful things there is also its black spot. In the Tovel valley the bear has a stable dwelling. In spite of the continuous war inflicted by man, the feared carnivore, protected by inaccessible cliffs and thick woods, remains there endagering the few visitors of the valley”. And he notes: “In order to put a stop to the thieveries of the beast, collecting the complaints of the poor mountain people affected in their vital interests, the noble Council of the Province of Trento, presented to the Ministry of Agriculture, a report calling for measures to rid us from this animal infestation”. Today celebrated by the Comunità delle Giudicarie as an “ante litteram environmentalist”, Bonomi considers the extinction of the bear an urgent public work, to be swiftly carried out: “The hunt for this formidable devastator of our herds continues with alacrity, and the day will not be far off when the species will disappear like so many others that preceded it”.13

For the cultural heirs of Sicheri and Bonomi, little or nothing has changed. One only need remember that Maurizio Fugatti – today President of the Autonomous Province of Trento – presented the decision to serve bear meat at a recent summer party of the Lega Nord in 2011, with these programmatic words: “To defend and protect the populations in the mountain areas of Trentino from the continuous visits of bears, we prefer to eat them in this way”.14

The extinction of bears in the Eastern Alps occurred at the turn of the 20th century: in 1835, the last bear was shot in Bavaria, in 1904 in Switzerland, and in 1913 in Tyrol. In South Tyrol, the last recorded bear hunt took place in 1930 in Val d’Ultimo (above). In 1939, the Hunting Act 1016 declares the bear a “protected species”.

“Each rustling sound startles us and makes us wonder”: An alternative Genealogy of the Tridentine Bear

And yet, rare hints of another sensibility, equally rooted in the alpine experience, creeps out from all corners of nineteenth-century literature. If the story of the bear in modern times is – as Michel Pastoureau claims – the story of a “fallen king”,15 the texts suggest that a scattered fringe of nostalgics do resist, they organise themselves and sometimes recruit new converts, passing down a sincere fascination for the old monarch of the woods. Even at the end of the nineteenth century, when bear hunting was raison d’état, there were those who saw local bears as something quite different from the infamous “devastators of herds” described by Bonomi.

Today less than a hundred bears continue to populate the mountains of Trentino. Yet, the presence of ‘l’Ors’ [the bear] remains deeply inscribed in the local toponymy. One may think of: Val de l’Ors, Ciasa de l’Ors and Busa de l’Ors in Val di Tovel, Pas de l’Ors on Monte Peller, Mandra de l’Ors near Carisolo, Costa de l’Ors near Stenico, Senter de l’Ors on Vallesinella, Gesol de L’Ors near Indovero, Tof de l’Ors at Molveno, Passo Bregn de l’Ors just above Lago di Valagola… a list that is by no means exhaustive.

One only needs to pay a visit to the Natural Science section of Trento’s University Library. Here we can browse through rows of texts by the celebrated Bonomi, passing by multiple volumes of Avifauna tridentina [Tridentine Avifauna] (1884), Nuove contribuzioni all’avifauna tridentina [New contributions to the Tridentine avifauna] (1889) and L’utilità dei boschi [The utility of forests] (1901), a paradigmatic and decidedly economic approach to “natural resource management” in which there is little place for the bear. A few meters ahead, we can pull out from the shelves L’Orso Trentino: cenni storico-naturali [The Trentino Bear: historical-natural notes] (1886) by the self-taught Francesco Ambrosi, a long-standing director of the Museum of Trento and founding member of the local Alpine Society (Società Alpinistica Trentina).

In the conclusion of his short volume of studies on the Trentino bear, Ambrosi writes, “The hunt for bears continues in Trentino in those parts where the bear has not yet taken a definitive leave. […] The war being waged against the bear is a war to the death; and everyone knows the power of civilised man. He wants what he wants, and if he wants he always wins, although his victories are not always conducted with that wisdom that Nature requires. She has goals that often go beyond human foresight, and woe to those who twarth them! Her vengeances are ready and terrible, and no man, however powerful he may be, can avoid them”.16 In these pages, Ambrosi seems to express a vague belated concern for a future void of mountain bears. And yet, something remains unclear. Why? What is lost?

To address this question, let us leaf through The Italian Alps (1875), by the English explorer and scholar Douglas William Freshfield: a splendid account, summarising about ten years of explorations in the Southern Alps. The book conveys a romantic fascination for the local alpine environments and an image of the bear that will become common place with the flourishing of modern mountaineering.

Every year, during the alpine carnival, l’Orso di Segal [the ‘Rye Bear’] comes back to run through the streets of Valdieri. The Bear frightens children, runs away from tamers, annoys passers-by, avoids the holy water of the exorcist friars: his awakening from hibernation tells people that the dark season is about to end. At the end of the feast the Rye Bear escapes, disappearing into the horizon despite the efforts and calls of the tamer.17 Photo credit: G. Bernardi.

Bears do not appear here as wild, demonic creatures (as in the late medieval period), nor as a negative factor in the political-economic calculation of national governments, local administrators and private entrepreneurs (as in the modern period), but rather as a spectre: an evocative relic of ancient times, whose invisible presence fills the mountain environment with a sense of sublime wonder. Describing the upper Val di Cluozza, Freshfield writes: “This valley has the appeal of being one of the few recesses of the Alps where bears are ‘at home’, even if they will not always show themselves to visitors. […] The dense pine woods, the bold bare peaks around and, above all, the romantic flavour imparted to the whole by the possibilities of bears, gave an unusual zest to our midday meal”.18

In Freshfield’s reflections – who would later become president of the prestigious Royal Geographical Society and of the Alpine Club – we find less attention to the economic value represented by the devastation of the plantigrade, than to the affective, imaginary and spiritual value of the bear’s presence. The presence of the bear – albeit invisible and silent – permeates the territory, stimulates the senses, stirring an awakening, an unusual presence-in-space.

Many people came to share this intuition. Almost a century after Freshfield, the naturalist Graziano Daldoss from Ledro denounced the imminent extinction of the Tridentine bear. He justified his calls for an urgent operation of repopulation with the following words: “When we walk through a forest inhabited by bears”, he wrote, “each rustling sound startles us and makes us wonder, all the shadows make us cautious and watchful. The fear and curiosity of being confronted by the yeti of our mountains makes every sensation more penetrating. A footprint, a scratch, excrements […] become as precious as fossils from a threshold between two eras: the era in which animals dominated and the era of our dried-up forests, where animals are no longer to be encountered”. This is why, Daldoss concludes, “the disappearance of the bear from our mountains is an untold loss”.19

According to the writer, director and Marxist theorist Pierpaolo Pasolini, the “disappearance of the fireflies” in the early 1970s coincided with and contributed to a profound anthropological transformation of the Italian people, now urbanised and consumed by consumerism.20 According to Daldoss, the disappearance of the bear from our mountains indicated the end of something equally profound, not economically quantifiable, nor technically reproducible.

Thus disappears what Reginal Grégoire – in a memorable text dedicated to the descriptions of hermitage in the alpine forests offered by the hagiographies of the 6th and 7th centuries – once called “the forest as religious experience”: a place of constant alertness, in which a sense of hovering danger impels us to maintain our otherwise fleeting attention to the surrounding-present.21

Eliminating the bear is tantamount to eliminating what makes the Alpine forest a space sui generis, i.e. a space that is culturally specific, historically distinctive, experientially different from the city park, or the uncultivated fields of the Po Valley. The anima loci of these mountains risks being lost; and a great Alpine epic and an entire form-of-life, would disappear with it.

M49 captured on camera on the slopes of the Marzola, after his first escape from the Casteller, on the night of Tuesday 16 July 2019. The total number of bears in the Tridentine Alps is now estimated to be between 82 and 94. 34 bears have died since 2003, 15 of which have died as a result of legal and illegal shooting.

Or may it be that the reappearance of the bear in our mountains represents a timid and unexpected sign that another life is still possible for us? Returning the bear to the mountain and the mountain to the bear – could this be a first step towards a conscious practice of collective rewilding, and a way of transforming our own way of living? Allowing space and time for a looming shadow, which forever escapes our control, may offer us the chance of rethinking our being-in-the-world. Could this be a way of renouncing our obsession for security – an obsession that demands the elimination of all sources of risk, the control of all life forms, and the suppression of all that deviates? May the bear teach us once again to wonder at ‘every single rustling sound’ and be present in and for this world?

References

[1] Pianesi, L. (2020) ‘Fugatti denunciato per maltrattamento di animali’, Il Dolomiti, 1 Ottobre. Available at: https://www.ildolomiti.it/politica/2020/m49-non-si-alimenta-e-scarica-le-energie-contro-la-saracinesca-m57-ripete-movimenti-in-maniera-ritmata-dj3-e-nascosta-fugatti-denunciato-per-maltrattamento-di-animali

[2] Trentino (2020) ‘Centro di Recupero della Fauna Alpina di Casteller’. Available at: https://www.trentino.com/it/sport-e-tempo-libero/bambini-e-famiglia/animali-in-trentino/centro-di-recupero-della-fauna-alpina-di-casteller/

[3] Lega Antivivisezione (2020) ‘Ispezione Carabinieri: Psicofarmaci su Orsi Casteller’, Available at: https://www.lav.it/news/cc-forestali-psicofarmaci-orsi-castellerx

[4] PNAB – Parco Nazionale Adamello Brenta (2010) L’impegno del Parco per l’Orso: Il Progetto Life Ursus, Rovereto: Manfrini. Available here: https://www.pnab.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/parco_documenti18_orso.pdf

[5] Corriere della Sera (2006) ‘Germania: L’orso “Bruno” è stato ucciso”, available at: https://www.corriere.it/Primo_Piano/Cronache/2006/06_Giugno/26/bruno.shtml

[6] Tondo, L. (2020) ‘Papillon the bear: how the ‘escape genius’ sparked a national debate in Italy’, Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/05/papillon-the-bear-how-the-escape-genius-sparked-a-national-debate-in-italy-aoeGuardian

[7] Montanari, M. (1988) ‘Uomini e orsi nelle fonti agiografiche dell’alto medioevo’, in Andreolli, B. e Montanari, M. Il bosco nel medioevo, Bologna: Clueb, p. 64

[8] Ibid. p. 66

[9] Varga, D. (2009). ‘Teddy’s Bear and the Sociocultural Transfiguration of Savage Beasts into Innocent Children, 1890-1920’. The Journal of American Culture, 32(2): 98-113.

[10] Benvenuti, A. (2017). ‘Il Santo, il Saltus e l’Prso. La Desacralizzazione Cristiana della Natura’. Storie e Linguaggi, 3(2), p. 295

[11] Finocchi, A. e Mussi, D. (2002). Sulla pelle dell’orso: la caccia nei documenti del passato e nelle memorie ottocentesche di Luigi Fantoma. Arco: Edizioni Sommolago. pp. 6-33

[12] Sicheri G.B. [1853] (1995) La caccia sull’Alpe, Stenico: Edizioni Circolo Sicheri, p. 12

[13] Zeni, M. (2016) In Nome dell’Orso: Il declino e il ritorno dell’Oso bruno sulle Alpi, Gavi: Edizioni Piviere, p. 112

[14] Ansa (2011) ‘Lega Nord, banchetto con carne orso; Pdl, fermate scandalo’. Available at: https://www.ansa.it/web/notizie/rubriche/cronaca/2011/07/01/visualizza_new.html_810143620.html

[15] Pastoureau, M. (2008) L’orso. Storia di un re decaduto, Torino, Einaudi, 2008

[16] Ambrosi, F. (1886) L’Orso Trentino: cenni storico-naturali, Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Edizioni, p. 43

[17] Agus C.A. (2015) ‘Il tempo dell’orso, l’orso nel tempo: L’exemplum dell’arco alpino occidentale’, in E. Combi-D. Ormezzano, Uomini e Orsi: morfologia del selvaggio, Torino: Accademia University Press: 15-40.

[18] Freshfield, D.W. (1875) Italian Alps: Sketches in the Mountains of Ticino, Lombardy, the Trentino, and Venetia, London: Longmans Green, p. 86

[19] Daldoss, G. (1981) Sulle Orme dell’Orso. Uno Studio Sull’orso Bruno del Trentino. Biologia della specie, origine e distribuzione geografica, Trento: Editrice Temi, p. 21

[20] See Pasolini, P. (1975) ‘Il vuoto del Potere’, Corriere della Sera, 1 Febbraio, p. 1.

[21] Grégoire, R. (1990) ‘La Foresta come Esperienza Religiosa’, in L’ambiente vegetale nell’Alto Medioevo, Spoleto: Edizioni del Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, p. 665

Bibliography

Agus C.A. (2015) ‘Il tempo dell’orso, l’orso nel tempo: L’exemplum dell’arco alpino occidentale’, in E. Combi-D. Ormezzano, Uomini e Orsi: morfologia del selvaggio, Torino: Accademia University Press: 15-40.

Ambrosi, F. (1886) L’Orso Trentino: cenni storico-naturali, Trento: Scotoni e Vitti Edizioni.

Ansa (2011) ‘Lega Nord, banchetto con carne orso; Pdl, fermate scandalo’. Available at: https://www.ansa.it/web/notizie/rubriche/cronaca/2011/07/01/visualizza_new.html_810143620.html

Benvenuti, A. (2017). ‘Il Santo, il Saltus e l’Prso. La Desacralizzazione Cristiana della Natura’. Storie e Linguaggi, 3(2), pp.289-302.

Bonomi, A. (1884) Avifauna Tridentina. Catalogo degli uccelli dei nostri parsi con osservazioni relative al loro passaggio ed alla loro midificazione, Rovereto: Tipografia Roveretana

Bonomi, A. (1889) Nuove contribuzioni all’avifauna tridentina, Rovereto: Tipografia Roveretana

Bonomi, A. (1901) L’utilità dei Boschi, Rovereto: Tipografia Roveretana

Cardini, F. (1986) L’orso, Abstracta, Agosto\Settembre, pp. 54-59.

Cardini, F. (2001) ‘L’orso’ in Mostri, belve e animali nell’immaginario medievale, available at: www.mondimedievali.net/Immaginario/Cardini/orso

Castelli, G. (1935) L’orso bruno nella Venezia Tridentina. Trento: Associazione Provinciale Cacciatori.

Cis, C. e Cis, P (2010) Caccia e Bracconaggio : la Caccia nella Val di Ledro dell’Ottocento, Riva del Garda: Tonelli Edizioni

Corriere della Sera (2006) ‘Germania: L’orso “Bruno” è stato ucciso”, available at: https://www.corriere.it/Primo_Piano/Cronache/2006/06_Giugno/26/bruno.shtml

Daldoss, G. (1981) Sulle Orme dell’Orso. Uno Studio Sull’orso Bruno del Trentino. Biologia della specie, origine e distribuzione geografica, Trento: Editrice Temi.

Faulkner, W. (2002) Go Down Moses, Torino: Einaudi.

Finocchi, A. e Mussi, D. (2002). Sulla pelle dell’orso: la caccia nei documenti del passato e nelle memorie ottocentesche di Luigi Fantoma. Arco: Edizioni Sommolago.

Freshfield, D.W. (1875) Italian Alps: Sketches in the Mountains of Ticino, Lombardy, the Trentino, and Venetia, London: Longmans Green.

Grégoire, R. (1990) ‘La Foresta come Esperienza Religiosa’, in L’ambiente vegetale nell’Alto Medioevo, Spoleto: Edizioni del Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, po.663-703.

Lega Antivivisezione (2020) ‘Ispezione Carabinieri: Psicofarmaci su Orsi Casteller’, available at: https://www.lav.it/news/cc-forestali-psicofarmaci-orsi-casteller

Massola, G. (2013) ‘Cavalcare l’orso: il topos dell’orso domato nell’agiografia medievale’, in Stopani, R. e Vanni, F. La via teutonica, Atti del convegno internazionale di studi. Venezia, 29 giugno 2012, a cura di Renato Stopani e Fabrizio Vanni, Firenze, Centro studi Romei, pp. 139-156 (available at: https://giorgiomassola.wordpress.com/2013/12/09/cavalcare-lorso-il-topos-dellorso-domato-nell’agiografia-medievale).

Montanari, M. (1988) ‘Uomini e orsi nelle fonti agiografiche dell’alto medioevo’, in Andreolli, B. e Montanari, M. Il bosco nel medioevo, Bologna: Clueb, pp. 55-72.

Osti, F. (1991) L’Orso Bruno Nel Trentino: Distribuzione, Biologia, Ecologia e Protezione della Specie. Xx: Edizioni Arca.

Pancheri, R. (2019) ‘Più orso che santo. L’immagine di San Romedio nell’Arte del Novecento’, in S. Spada, Ursus. Storie di uomini e di orsi, Trento: Edizioni del Comune di Cles, pp. 161-175

Pianesi, L. (2020) ‘Fugatti denunciato per maltrattamento di animali’, Il Dolomiti, 1 Ottobre. Available at: https://www.ildolomiti.it/politica/2020/m49-non-si-alimenta-e-scarica-le-energie-contro-la-saracinesca-m57-ripete-movimenti-in-maniera-ritmata-dj3-e-nascosta-fugatti-denunciato-per-maltrattamento-di-animali

PNAB – Parco Nazionale Adamello Brenta (2010) L’impegno del Parco per l’Orso: Il Progetto Life Ursus, Rovereto: Manfrini. Available at: https://www.pnab.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/parco_documenti18_orso.pdf

Preston, C. (2020) ‘Why Italians Are Growing Apples for Wild Bears’, The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/04/what-wildlife-really-looks-like/609721/

Spada, S. Ursus. Storie di uomini e di orsi, Trento: , pp. 161-175

Pastoureau, M. (2012) Bestiari del Medioevo, Torino, Einaudi

Sicheri G.B. [1853] (1995) La caccia sull’Alpe, Stenico: Edizioni Circolo Sicheri

Snyder, G. (2010). The practice of the wild, San Francisco: Counterpoint Press.

Tondo, L. (2020) ‘Papillon the bear: how the ‘escape genius’ sparked a national debate in Italy’, Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/05/papillon-the-bear-how-the-escape-genius-sparked-a-national-debate-in-italy-aoeGuardian

Trentino (2020) ‘Centro di Recupero della Fauna Alpina di Casteller’. Available at: https://www.trentino.com/it/sport-e-tempo-libero/bambini-e-famiglia/animali-in-trentino/centro-di-recupero-della-fauna-alpina-di-casteller/

Varga, D. (2009). ‘Teddy’s Bear and the Sociocultural Transfiguration of Savage Beasts into Innocent Children, 1890-1920’. The Journal of American Culture, 32(2): 98-113.

Zeni, M. (2016) In Nome dell’Orso: Il declino e il ritorno dell’Oso bruno sulle Alpi, Gavi: Edizioni Piviere.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »