Temporary wastelands: a visit to the Fukushima evacuation zone

In 2011, a series of infrastructural failings following the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami triggered a radiation leak today known as the Fukushima nuclear accident, leading to the evacuation of around 200,000 people. By the time photographer Philipp Zechner visited the area 8 years later, restrictions were limited to parts of the town of Namie. With the media debate now cooled, Zechner explores what has remained and what has been lost in this place, capturing the physical as well as the emotional landscape to provide a nuanced perspective on the enduring impact of the catastrophe.

I first came to Japan in the year 2000, and subsequently lived there for almost 5 years, starting in 2004. Having made many friendships and learned the language, I have been coming back ever since, visiting many parts of this country – it never ceases to fascinate me. One thing that I learned during one of my first visits is that nature in Japan, beautiful as it is, has a more destructive power than that we are used to in Northern Europe. Earthquakes strike frequently and during the rainy season, rivers swell up to the borders of their dams, while the southern regions, in particular, get struck by typhoons. Those are the known risks that people (have to) accept and prepare for with admirable stoicism. And most of the time, their preparations are effective, preventing damage.

By definition, an accident is something that happens unexpectedly. In Japan, almost every other year, some region of the country is hit by a calamity. Yet in most cases, the effects are mild, due to a high level of preparedness and various preventive measures. So when disaster struck on 11th March 2011, it was not the occurrence of a major earthquake and tsunami that terrorised and paralysed the country, since both had been expected to arrive at some point, rather, the failure of all preventive measures in the face of the enormous scale of the events. The backup electricity generators were flooded and the seawalls at the shore overrun – the technology and infrastructure to protect the population were in place, but it failed.

A landfill for contaminated soil.

Top image: The devastated coastline near Namie.

I visited the Fukushima evacuation zone in late 2019, just some months before the pandemic put a halt to international travel. While the topic had been hot and widely discussed in Japan immediately after the disaster, with citizens’ movements forming and demonstrations against nuclear power attracting masses on a scale that was unthinkable before, the discussion had somewhat calmed down by that time, although in Europe there were still many articles, mostly dealing with topics like resettlements, discrimination of the inhabitants, and the release of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean, often with an accusatory undertone. In this somewhat ambiguous information space, I wanted to go and see for myself what it was all about some years after the catastrophe of 11th March 2011. There are small tour operators that are now permitted to enter the zone, so it can be reached legally and without too much of a problem.

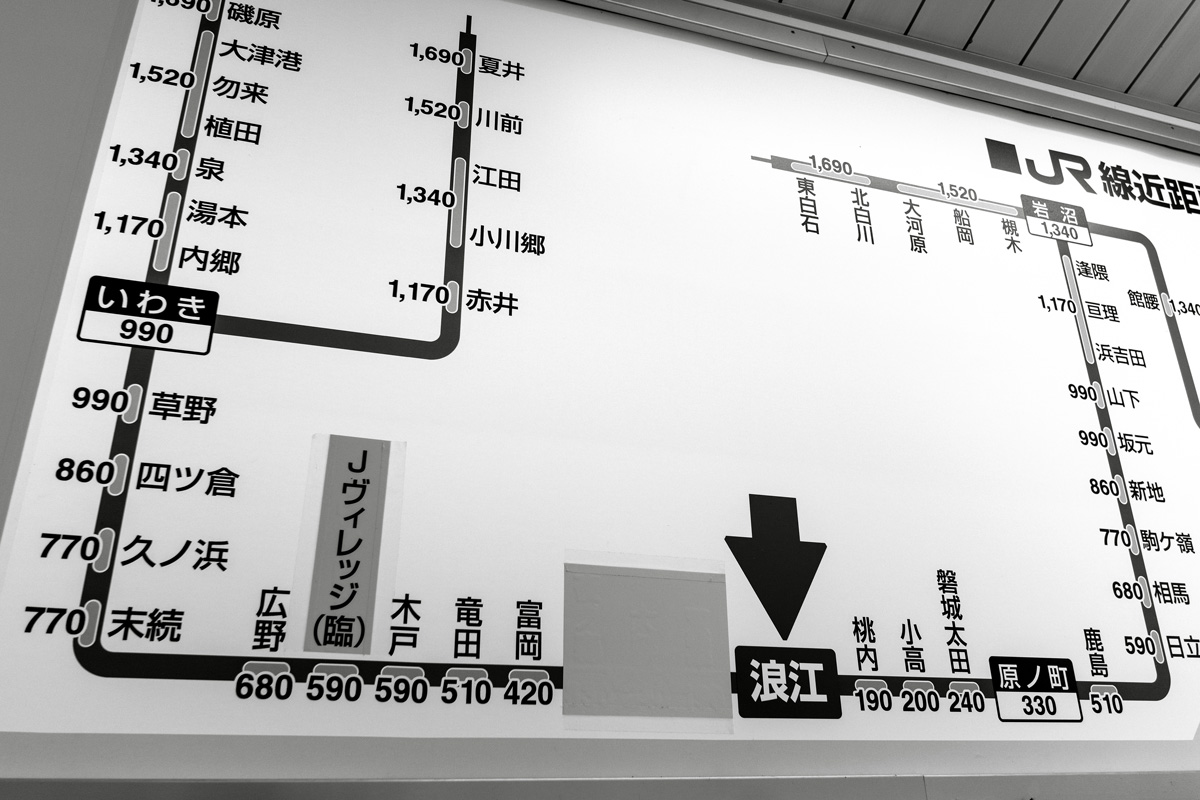

A railway plan in the region of Namie, 2019. The stations that are not served because of being in the evacuation zone have been greyed out, while the train keeps running.

An overgrown building in central Namie.

In some parts of the coastal area, the devastation was almost total, while in other parts, a bit further inland, the cityscape remains almost intact after several years, as if the buildings had just been left some days ago. Only a closer look reveals the state of abandonment. By 2019, the evacuation order had been lifted for many of the affected cities, although parts of Namie remain restricted still today. It is a fact, however, that many of the former inhabitants have not returned to their old homes, leaving them as they were on the day of their sudden departure.

Abandoned houses in the town of Namie.

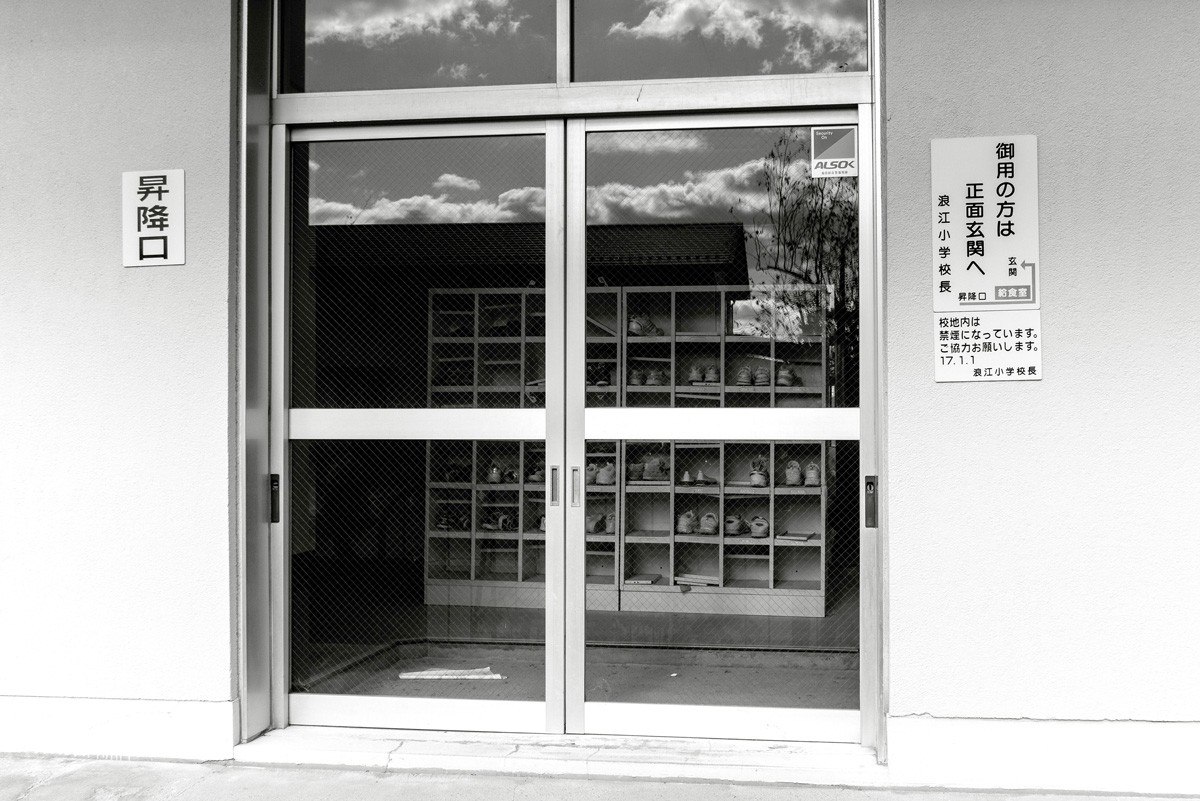

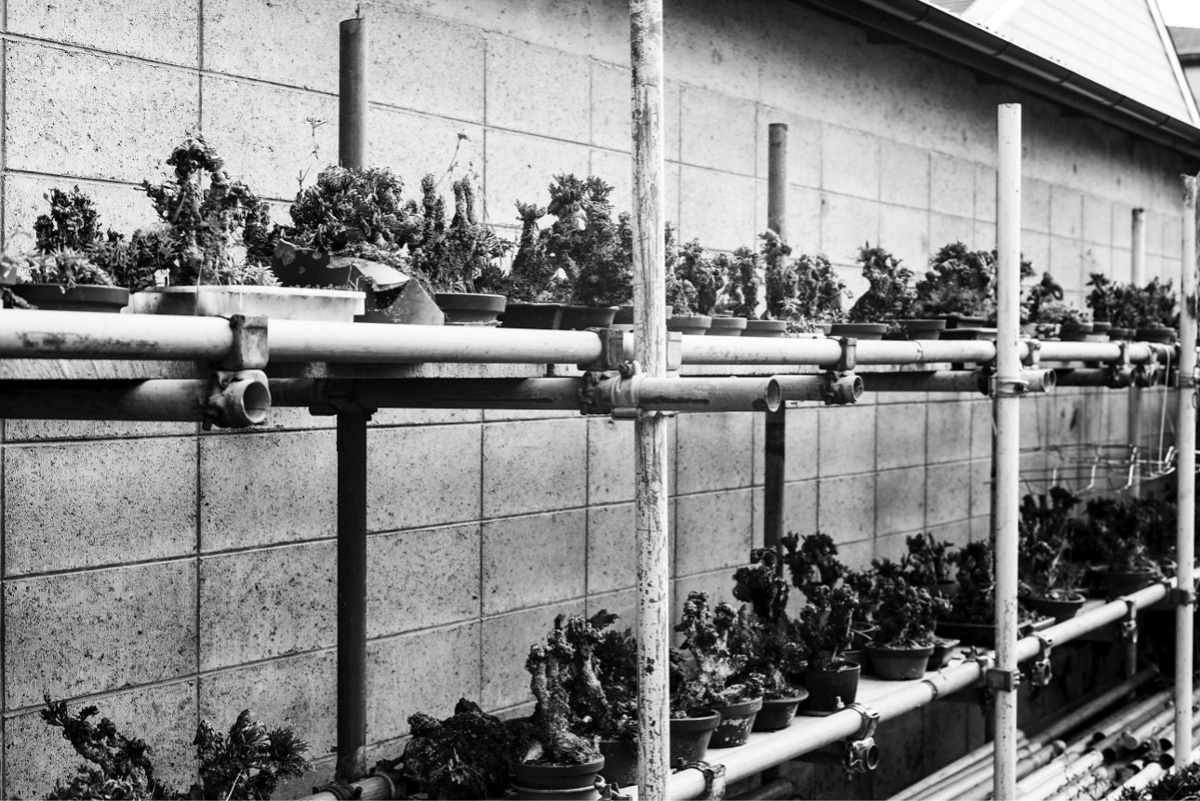

Modern buildings in Japan are built to withstand even strong earthquakes, so what has worked on the city is essentially time and, in some cases, vandalism. Some windows are broken, some places overgrown, and in a courtyard, I came across dozens of bonsai trees, neatly arranged on a shelf but all dried up since nobody takes care of them anymore. Radiation is tricky since it cannot be seen, so the uninformed visitor could easily marvel at what invisible force made the inhabitants rush off in such a hurry, leaving things behind as they were – shirts on the clothesline, slippers at the doorstep…

Abandoned slippers at the entrance of Namie Primary School.

Withered bonsai trees in a private courtyard.

I had the chance to talk to some of the inhabitants during lunch at a restaurant in the open part of the city, one of the few places where people would gather at that time. There were voices deploring the lack of governmental help, but what seemed to prevail was a feeling of overall sadness. An elderly woman told me that she was happy to be back, but that her city had changed so much, with many of her neighbours and families with children gone.

On the other hand, nobody I talked to felt offended by a tourist coming to visit their hometown, quite the contrary. Since there is still some taboo around the region, they were actually happy to see visitors come back – a sign of normalisation in a place that still has so many restrictions.

Trucks removing debris and contaminated soil in the evacuation zone.

Bags with contaminated soil piled up at the roadside.

It may be unfair to compare the Fukushima area with the Chernobyl exclusion zone, which has remained in a kind of sleeping beauty slumber for many years, circumstances being very different, including the economic ones. What can be said, however, is that right from the start, the authorities refused to abandon the contaminated region, with considerable efforts being made to clean the area and enable the population to return – sooner or later. There are large landfills where countless plastic bags, filled with contaminated soil, are dumped with lines of trucks rolling through the zone day and night. The supermarkets in the area are populated by middle-aged men, workers who have been lured here by the promise of attractive pay. There are reports of unskilled workers being deployed to areas with high radiation, of health risks and insufficient protection, some of which are discussed in the mainstream media. What seems clear, however, is the political will to reconquer the affected areas and make them available to future generations. This is an endeavour without precedents – how long this will technically take, as well as how much time is needed before people feel emotionally ready to resettle in the region, remains to be seen. Yet despite the intricate problems related to human and nonhuman life in the area, one thing seems certain: technology will once again be used to patch up open wounds and alleviate potentially damaging consequences. Here, as elsewhere, a continuous cycle of human struggle to control natural forces endures.

A solar-powered Geiger counter at Namie station.

The coastline at Tomioka, with reinforced flood walls and the silhouette of the Fukushima Daini Power Plant in the background.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »