Heart of stone

What role can public art play in constituting the experience of a place? For fifteen years, Mili Romano has curated Heart of Stone, a series of multidisciplinary interventions in the town of Pianoro, in the province of Bologna. Morphologically transformed by redevelopment processes imposed from above, this small village, already profoundly affected by the events of the Second World War, has found an opportunity for social aggregation and resistance within public art. This is the story of a progressive, personal shift from theoretical research on literature and urban anthropology to creative action within the city, realised through collective and participatory design practices.

For 15 years, since 2005, I have curated a public art project titled Heart of Stone for Pianoro, a small Italian town in just outside of the city of Bologna. Over the years, artists have collaborated with schools, associations, and residents to create a series of temporary and permanent installations scattered throughout the town, creating a relational and participatory trail that stretches from the town centre to its green areas and industrial complexes.

Situated on the State Road 65, which connects Florence to Bologna, Pianoro has had lived several lives. During WW2, the town was a strategic point at the end of the so-called Gothic Line – a fortification system built by the Nazis during the Italian campaign. As the Anglo-Americans pushed north, the area became the backdrop to heavy clashes between the Axis and the Allies, with Pianoro itself being subjected to a number of brutal shelling and air bombings. In a relatively short time between October 1944 and April 1945, this led to the almost complete destruction of the village. It was one of the most devastated in the whole of Italy, so much so that its reconstruction was practically impossible.

This is why, in the immediate post-war period, a new town named Pianoro Nuovo (New Pianoro) was founded just three kilometres north of the rubble. The aim was to provide accommodation for those forced to evacuate their homes due to the bombings, fleeing to Bologna and the nearby countryside. Yet it wasn’t just the new buildings of Pianoro Nuovo that made it a new place. It was also home to a new political struggle that, as in other areas of northern Italy, was here felt with particular intensity: known in Italian as Resistenza (literally ‘the resistance’), the movement was propelled by a loose coalition of anti-fascist groups that took part in the war with both direct clashes as well as acts of disruption and sabotage. This memory of the resistance is still tangible throughout the town’s urban structure, not only in the monuments to the fallen but also in the many roads that were named after the partisans who took part in the fights. But aside from its material signs, the memory of the resistance still functions today as a strong cohesive element for the town’s inhabitants.

However, even this new village, designed by Alberto Legnani in the 1950s, suddenly changed. The year 2005 marked the beginning of a profound urban transformation of the town centre, with a redevelopment plan that involved the demolition of the entire old market square and Pianoro’s postwar edifices. While the intention was to create modern, efficient, commercial buildings, for Pianoro’s residents the redevelopment was felt traumatically.

All those elements of neighbourhood community practices – green areas, collectively-tended to vegetable patches, public paths and outdoor meeting places, including the chairs and the tables where people played cards in the street – were obliterated from the space in a few months.

Heart of Stone manifesto. Photo by Mili Romano

Of course, this is nothing new: it happens regularly, at least outside of those monumental historic centres, in every big and small city marked by the laws of impermanence. Yet here in Pianoro Nuovo the novelty lies in a desire to transform this process of oblivion into a critical awareness, through artistic creations in parallel with a continuous collective narration. This was something quite uncommon for Italy, especially back then.

That which has been excluded will haunt us in the form of symptoms, maintained psychoanalyst Carl Jung. And psychologist James Hillman, who cites Jung in his The Soul of Places, suggests that the experience of ‘repression’ – in this case understood as the physical sense of destruction and erasure of entire areas of cities – is accompanied by creative and prolific questions about the place. In addition to keeping the memory intact, actively participating in a common project may also allow for something else to resurface – something that often fails to have a voice. That which is removed, in this case the inhabitants’ experiential history, may emerge from oblivion and become, with a little therapeutic activity, a force for change.

We had already attempted something similar back in the mid-1990s when I curated a project entitled Accademia in Stazione. It was a series of site-specific works created by the students of the Bologna Academy of Fine Arts to commemorate the railway station massacre that took place in 1980, when a neofascist terrorist bomb detonated in one of the station’s waiting rooms, killing 85 people and wounding over 200. For this project, we challenged the usual approach of producing merely decorative sculptures or monumental works, and instead opted for a series of interventions that were much more connected to the context and specifics, even in anthropological terms, of the place.

The idea of turning a memory – and in this case, the traumatic memory of a massacre – into a vital force, as well as the belief that art can be a powerful device for cultural change and improvement of the quality of life in public spaces, is what made me move from theory and representation to action.

Whether ephemeral or permanent, public art can affect places and their inhabitants, making every sign a source of new meaning and memory. And this is ‘not for profit’, as philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes. As a counterbalance to a society entirely centred around consumption and indifference, public art intrudes into the slow process of public space transformation into affective spaces, whereby relationships, emotions, and collective experience all contribute to the formation of a new soul of the city.

Heart of Stone was born from this spirit with a series of exploratory walks that turned into a poetic-political gesture. I started to affix red posters – a colour that recalls the theme of the Resistance – on the billboards between Pianoro and Bologna, as well as outside the doors of flats that were awaiting demolition but still inhabited. The invitation was for the inhabitants to display the posters on their windows as a sign of their willingness to collaborate on the project.

MP5, Urban Comics. Photo courtesy Claudia Paniewski

There was no nostalgia and no rhetoric in this, only the reactivation and narration of memories through a daily exchange with the artists. One of the fundamental methodological assumptions of Heart of Stone was the idea of a work that would grow and develop with collective commitment and responsibility; a project that would have to be taken care of for a prolonged period of time, from the design envisioned by the artist, to its curatorial aspects and its maintenance and care.

In other words, it is a work in progress, in which those involved must let themselves be shaped and influenced by the space, the context and the unexpected events that occur within it. It is a work of transformation and sedimentation; it is demanding. It is not an artwork fits well with the spectacular nor the rapid patterns of consumption in which the art system moves.

Quite the opposite, this is a work that grows within the folds of the place, gaining deep meaning for those who contributed to its creation.

‘High’ and ‘low’ merge together and dialogue. As I see it, it is the slow weaving of a human, artistic, social, and anthropological plot. After all, when it comes to public art the ‘methodology’ – if we can speak about the existence of a methodology at all – is basically nothing but a walk, a path, at least if we consider what Hillman maintains. A walk open to the unexpected.

My walk and those undertaken by the other artists to explore the public spaces during the design stage were and still are repeated with the inhabitants, with school kids, with the Academy’s young artists, as well as by the public during the openings.

Since its beginning as a response to an urban planning emergency, Heart of Stone has focussed on issues that have continued to surface during the explorations undertaken with the community over the years. During the economic crisis, the project became Heart of Stone/Work. For this iteration of the project we organised an intense exchange with 36 local companies and industries. During the migrant crisis, Golden Waves instead focussed on the reception and integration of migrants within the local area.

Below are a selection of stories behind some of the many works that have been realised.

* * *

Andreco, A hidden ontological resistance (icons from resistant work). Photo courtesy Gabriella Presutto

Andreco. A hidden ontological resistance (icons from resistant work)

A set of icons brings to mind the resistance and the post-war reconstruction work in Pianoro. By collecting the testimonies of the many elders who lived through that time – Gianpiero, Luciano or partisan Morgan, Marisa – artist Andreco and the young students of the Bologna Academy of Fine Art have each drawn signs that refer back to those times.

These include the bicycle of the partisan relay girls; the boots for the hard walks; a caltrop, given to Andreco by Andreina who received it from her father, used for stopping and damaging Nazi trucks; women’s hands handing out bread or food; as well as two ritual signs depicted by Andrew: the partisan, and the tree that sinks its roots into the depths of the earth and rises to the sky. As Andreco remarks:

“The most effective way to keep the spirit of the partisan struggle alive is to practice it everyday, right now. What pushed those women and men to fight oppression and gain freedom are feeling that exist in each human being, so you don’t have to wait for a war to become aware of them.”

* * *

Mili Romano with Studio Ciorra and Sabrina Torelli, Light Path. Photo courtesy Marco Mensa

Mili Romano with Studio Ciorra and Sabrina Torelli, Light Path

Locals expressed a desire to remember their small wooden gazebo, which stood in the old garden, and where they used to gather to play cards during the summer. Hence Light Path, a pavilion made of iron and coloured glass. It’s very fragile, but it’s been there for fourteen years, never vandalised.

Different generations and cultures quickly found a place to meet for renewed sociability, accompanied by the amazing plays of colour that the light filtered through the glass draws day and night, in a sort of spontaneous colour therapy.

On some of the glass panes is the sandblasted sketch of an ancient map of the area, with at its centre the silhouette of a human figure – the bearer of harmony, a character from a fairy tale written and drawn by the local children with artist Sabrina Torelli. A little boy, on the day of the inauguration in 2010, said that this small pavilion is ‘the protective spirit of the town’, the soul of the new Pianoro, and told us that there should be a ‘light path’ in every town.

* * *

Sandrine Nicoletta, How does the planet turn and I with it? Photo by Mili Romano

Sandrine Nicoletta, How does the planet turn and I with it?

This is the phrase the artist carved on a boulder brought from a valley crossed by a river. Starting from that question and that boulder, many young people and school children have developed fantastic narratives, producing poems, musical compositions (with Anna Troisi), or cartoons. Children continue to play on and around it.

Far from being a static and invisible ‘monument’, it is a rock in constant metamorphosis, always in a process of becoming something else. When we presented it to the public in 2007, the garden was still a construction site, it was raining and there was mud. I saw astonishment in those who expected to come and see something beautiful.

I then said that that construction site was akin to contemporary art in cities – it is always open. And that ‘beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all’, as André Breton writes in Nadja. It is living and changing beauty.

* * *

Zimmer Frei, Mine! Photo courtesy Lino Acconcia

Anna Rispoli, Zimmer Frei, Mine!

A lighting piece made from all the chandeliers that the inhabitants of the old homes to be demolished donated before moving into their new places. Each chandelier is linked to a specific story – of Giulia, Lina, Elena, Gianpietro, Arkia and many others.

The piece was installed under the City Hall portico, as well as in two other porticoes along the streets of the new village centre, where they remained for many months. It was supposed to be a permanent installation, an August storm broke a chandelier, luckily without harming anyone. The project had then to be changed, adapting to the unexpected. A work in public space (as well as the artist who made it) must be ready to face the pitfalls of nature or chance.

That is why one day in January 2009, Tuo! (‘Yours’) took place in the public piazza. It was an auction that distributed those unique installation pieces to the highest bidders: no money was exchanged though, only payments in kind (home-made pasta, acupuncture sessions, a photo shoot or other), as well as one’s time and services for Heart of Stone. It was as though the old anthropological ritual of the Kula found a space and a time in the streets of this northern Italian village.

* * *

MP5, City look at City. Photo by Mili Romano

MP5, City look at city

In two 20 square meter platforms, reconstructing the plan of the old square, are the miniature buildings on whose exterior walls are reproduced in giant comic strips objects, furniture, domestic rituals of the inhabitants of the old houses. This collection of comic strips, drawn by the artist together with school pupils and after many visits and interviews with the inhabitants, was originally envisaged to be displayed as a temporary installation on the fencing of the construction sites, but later became a permanent installation. It is interesting to note how a project can acquire a temporal dimension of transformation and evolution.

* * *

Valeria Talamonti. Remember me. Performance documentation

Valeria Talamonti, Remember me

An unusual use of a mirror that for the artist assumes another identity and a country in transformation. A performance that, during the opening, accompanied the walk by asking the public and passersby to look at themselves in the mirror.

* * *

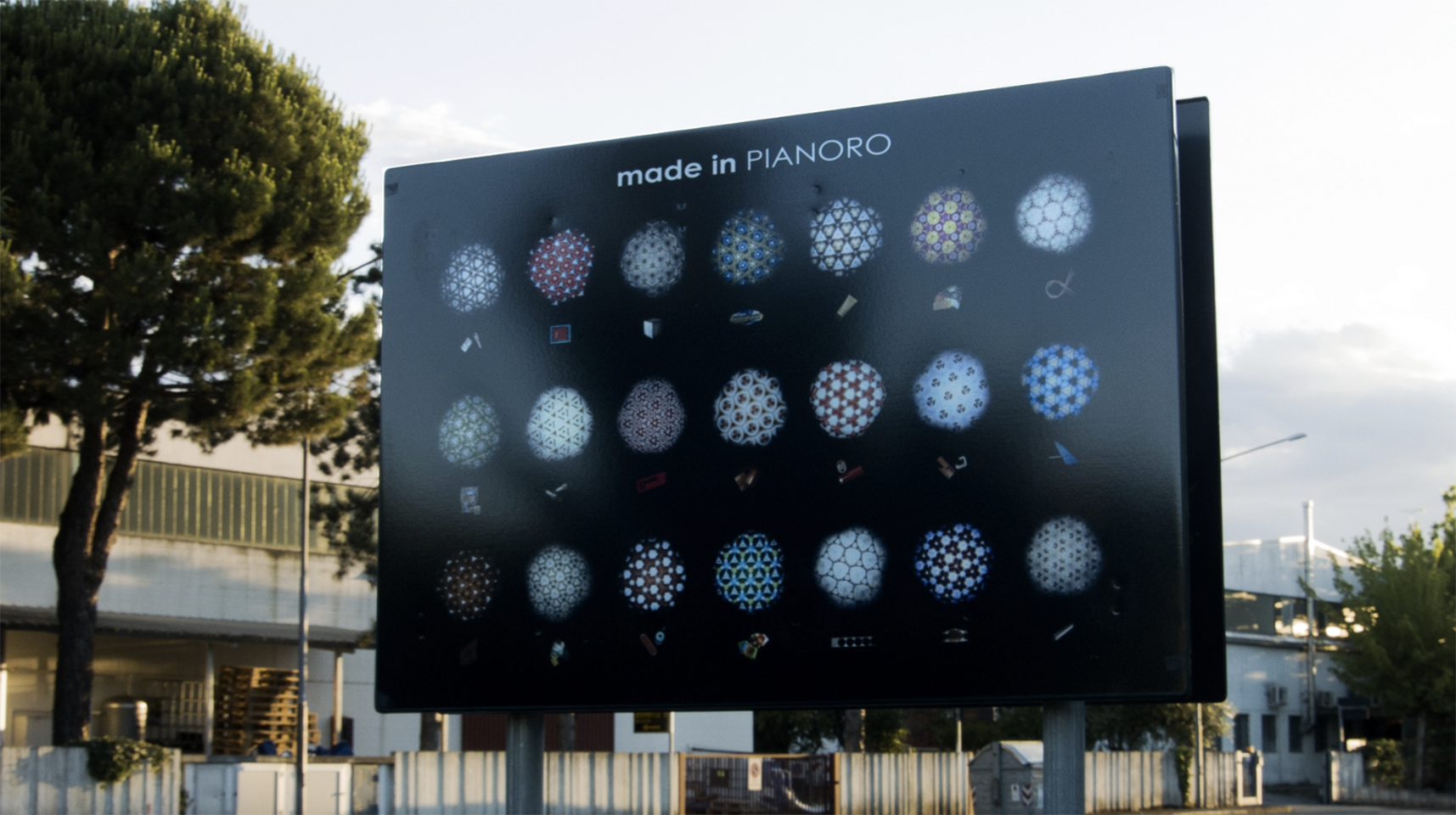

Anna Rossi. Made in Pianoro. Photo courtesy Marco Mensa

Anna Rossi. Made in Pianoro

Objects and production waste, photographed through a thaumatrope repropose, on road signs, which unite the center of the town with the industrial areas, the real object and its transfiguration into a fantastic microcosm.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »