Future memory and the thief of time: traumatic urbanism between the imaginary and the real

In Gaza, the experience of perpetual conflict translates into an architecture that rises directly as ruin. The buildings of the territory are the expression of a structural temporariness that paradoxically embeds the weight of an eternal present. Palestinian architect, Hania Halabi, reflects on how architecture may offer the foundations for psychological recovery, through its intricate relation to the temporality and emotion of inhabiting.

Gazans have been living in and amongst ruins since at least the early twentieth century. Their continuous conflicts with Israel have piled layers of ruins on top of each other that are difficult to tell apart. Following the Palestinian democratic scene of the 2006 Legislative Council elections, and the victory of Hamas over Fatah, a series of destructive wars have taken place accumulating three new layers in less than a decade. During these years, Gazans have also been suffering from severe trauma, without sufficient time between the subsequent wars to heal. Today, Gaza is a stratified urban space of both material and immaterial ruins. By the latter, I am referring to the psychological condition that results from conflict, and which is often coupled with a lack of resilience, along with a drifting socio-ecological system.

The material and immaterial ruins of Gaza, as overlapping layers, form a laboratory for exploring concepts that lie at the intersection between architecture, conflict and emotions. Whereas many efforts are either put into developing sustainable reconstruction methods or enquiring into post-war psychological conditions, less attention is paid to the intricate interlocking relationship between the two.

This article aims to disclose this entangled relationship by using time as an unfolding element. Time is thus no longer addressed as a dimension of space in which different events take place, but rather as a navigational tool by which the intimate link between architecture, conflict and emotions is revealed. Moreover, time becomes a medium through which reconstructing buildings and reconstructing emotions are reconsidered as a single process.

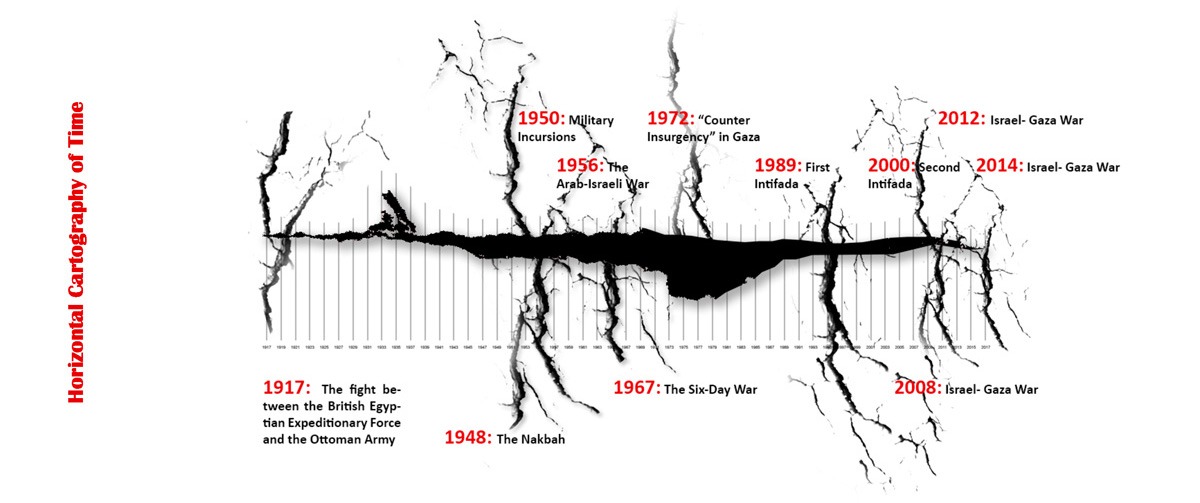

Mapping Gaza’s History: A Cartography of Horizontal & Vertical Times

The fact is that spatial form is the perceptual basis of our notion of time, that we literally cannot ‘tell time’ without the mediation of space. W. J. T. Mitchell 1

The Palestinian – Israeli conflict has been ongoing for at least a century now. Thus, an enquiry into any particular event throughout this long journey of struggle cannot be made in isolation from its historical context. However, as historian Hayden White has argued, historiography should employ a chronological timeline in which events are not addressed as a mere sequence, but are rather revealed as entities possessing structure – an ‘order of meaning’.2 This inevitably leads to the question of visual representation. How do we draw time in this way? What does the history of Gaza look like?

Theories of time have been greatly debated; whereas some theorists assert the objectivity of the passage of time and its linearity, others argue that it is purely subjective or socially constructed. Time may be described as a dimension of space where the past, present and future coexist. But no matter which description may convince us more, we all experience time in relation to the space we inhabit, and even though our experiences differ, we all decay.

Gaza’s horizontal timeline begins with the fight between the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force and the Ottoman army in March 1917, followed by the Nakbah in 1948, the military incursions of the 1950s, the 1956 war, the 1972 ‘counter-insurgency’ in Gaza’s refugee camps, and the first Intifada of 1987-1989. The year 1993 witnessed the start of the Oslo peace process but it wasn’t long before the second intifada commenced in 2000. Each of these conflicts has piled new layers of rubble on top of those produced by their predecessors. Today, three layers of ruins have been added in less than a decade as a result of the destructive 2008-2009 war, the 2012 conflict and the 2014 war.

A different perception of these historical events in a vertical timeline, read in relation to the ground, gives another dimension to understanding the context. After the Nakbah in 1948, Palestinian refugees who make up to 70% of Gaza’s population built many of their houses without foundations. This has materialised the perception of their life in refugee camps as a temporary solution until they acquire their right of return. Following that, Gazans have continued to build and are still building fragile temporary structures, always considering the constant possibility of destruction in a coming war. Temporariness, in this case, holds a political statement that would be lost otherwise.

Gaza as a Space of Pre-emption: The Architecture of Ruins in Reverse

It is of no doubt, that Gaza, with its permanent temporariness, inhabits a liminal condition. It is continuously positioned at a threshold between a traumatic past, which it can never entirely overcome and a blurry future that it hopes to be brighter. The liminality and fragility of this condition make it almost impossible to plan. As Brian Massumi explains in his interview ‘The Space-Time of Pre-emption’, this is because living with threat entails a posture of pre-emption. Whilst danger lurks in the present from a past chain of events; threat lurks from the future as a surprise – it is always there but never clear.3 Those who live with threat are therefore constrained to a pragmatic posture of preparation for what is yet to happen.

With such an understanding of Gaza’s context as one of pre-emption, we can read the constructions of Gaza as what artist Robert Smithson refers to as ‘ruins in reverse’, introduced in his article ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’. Unlike the romantic ruin, Smithson argues that some newly constructed buildings, such as those found within the forgotten suburbs of the United States, ‘don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise as ruins before they are built’.4 Smithson thus makes an important shift in our understanding of the ruin as requiring a different relation to time, since such areas ‘exist without a rational past and without the “big events” of history’.5 In relation to Gaza, whose history has been, and continues to be in, an incessant process of destruction, perhaps its reconstruction needs to be considered through a reversed lens of time – constructing to rebuild an obliterated past, which in turn will create the space for future imaginings.

Between the Imaginary and the Real

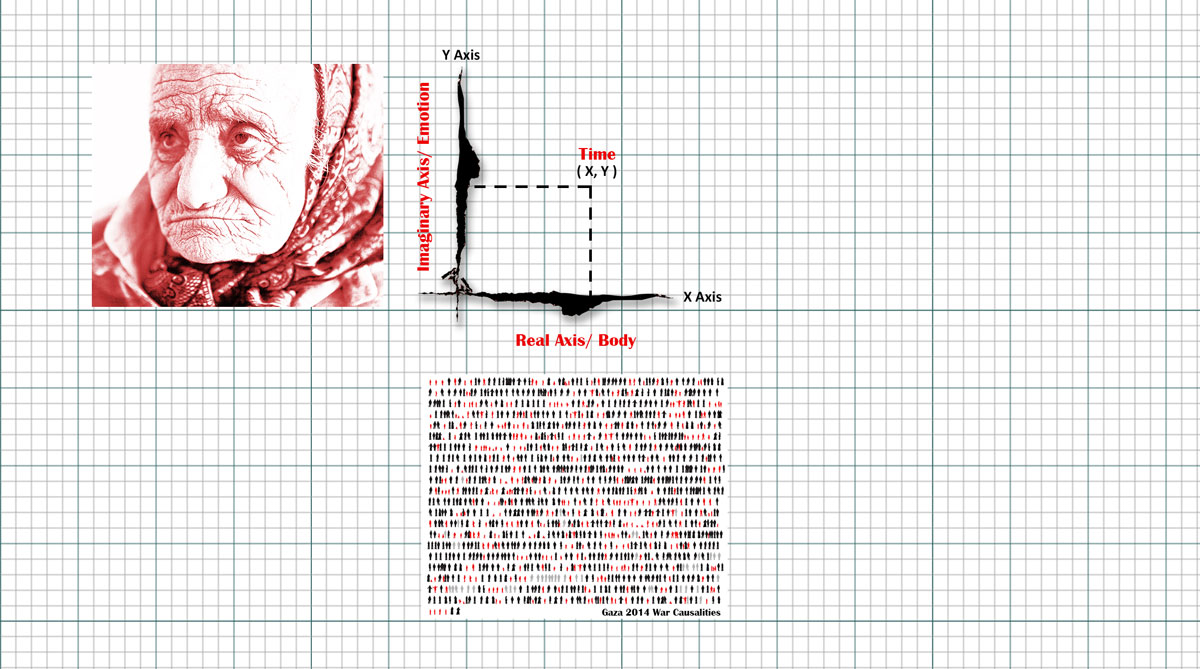

If we turn the horizontal (chronological) and vertical (spatial) timelines of Gaza into a Cartesian x and y axes, where do emotions lie in relation to time and space?

In his essay ‘Time and Dimension’, architectural designer, Cecil Balmond, describes time as a nonlinear concept and draws an analogy with complex numbers in mathematics. Whereas complex numbers are a compound of a virtual y-axis, and real numbered x-axis, time, according to Balmond, may be compounded in a similar way between the emotional on the y, and the body on the x. Body-time is biological time, which humans have quantified into hours, minutes, and seconds, but which is fundamentally buried in our cells, chromosomes, and is the reason behind our decay. Emotional-time, on the other hand, is subjective, accelerated or decelerated by feeling.6

Time’s graph is a plot of mixed moments, body-time with emotional-time. Such a plot of time’s duration and experience would be like the signature of a fractal, amazingly varied, yet self-similar and somehow ordered by hidden rules. Cecil Balmond 7

Such a compounded experience of time is subject to continuous fluctuations, and according to this plot, ‘when the experience lies completely on the y-axis of emotion, time as duration becomes zero. ‘Feeling’ is everything. I am not aware of measure’.8 In other words, when emotions are all-encompassing, time vanishes.

Trauma and threat, as discussed, create a permanently liminal condition in which postures of pre-emption are the only possibility. The past is obliterated and future imaginings are inconceivable with the continuous threat of destruction. In this scenario, affect is everything and time is lost: trauma is the thief of time. But with this realisation comes another: that the reconstruction of buildings and emotional recovery should be thought of as a single process. If we are to design in contested territories such as Gaza, where a history of destruction also reflects future conflict possibility, it is important to consider time as the hidden link between architecture and emotions. In these spaces of pre-emption, where emotions of trauma, grief and loss are highly embedded, perhaps architecture can also build time – restructuring the past, which despite its traumatic memories, houses the space for projected blurry futures.

Footnotes & references

[1] Mitchell, W.J.T. (1980). ‘Spatial Form in Literature: Toward a General Theory’. In Mitchell, W.J.T. (ed.). The Language of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p.274

[2] Rosenberg, Daniel & Grafton, Anthony citing White. (2012). Cartographies of Time: A History of the Timeline. New York NY: Princeton Architectural Press. p.11

[3] Rice, Charles. (2010). The Space‐Time of Pre‐emption: An Interview with Brian Massumi. Archit Design, 80. pp.32-37

[4] Smithson, Robert. (1967). ‘A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’. In Flam, Jack (ed.). The Writings of Robert Smithson: Essays With Illustrations. (1996). Berkeley and Los Angeles CA: University of California Press. p.72

[5] Ibid.

[6] Balmond, Cecil. (2013). ‘Time & Dimension’. In Crossover. London & Munich: Prestel. pp.616-625

[7] Ibid. p.620

[8] Ibid. p.621

All text and images © Hania Halabi 2019, unless stated otherwise.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »