In comics, when do landscapes change from setting to subject? Usually thought of as the backdrop to the unfolding of events, the landscape often plays a deeper role. In this article, semiologist Daniele Barbieri recounts some moments found within the history of comics in which the landscape becomes an important protagonist.

Comics are born humorous, later they become tinged with fantasy and adventure. When humorous, the landscape in the comic is usually not very relevant; in adventure comics, the landscape is functional to the story – a pure description of the situation faced by the hero. However, from the 1960s onwards, an expressive transformation takes place. Progressively, with more and more importance, the inner-looking psychological storytelling takes hold in comic strips. First, it is disguised within a particular form of adventure or humour, then becoming more and more autonomous, more and more a genre of its own, ultimately sanctioned by the advent of the graphic novel format.

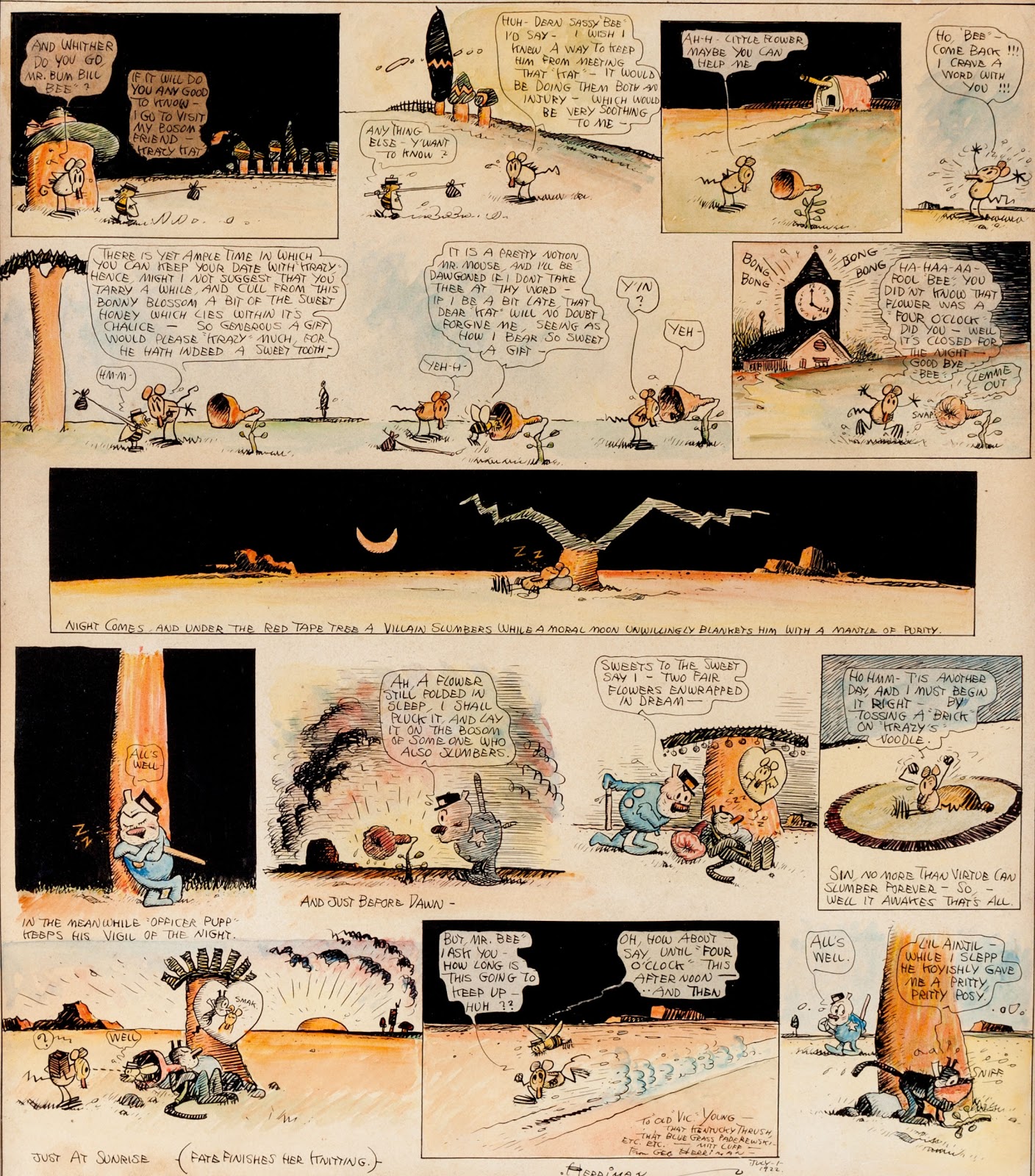

However, as often happens, there is an important precedent to this development. As early as 1911, George Herriman invented Krazy Kat, a humorous strip based on the endless torment of the impossible love of a cat for a mouse, each time mandatorily ending with the mouse throwing a brick at the cat’s head.

Krazy Kat by George Herriman, 1922

During the 33 years of Krazy Kat, the impossible love between cat and mouse is iterated in all its possible forms, with astonishing expressive sensitivity. This is also achieved with the birth of a community of characters and a place where events unfold: Coconino County.

Coconino County is the first expressive landscape in the history of the comic strip: behind the characters – even when these are evidently motionless – the world continues to transform, like the background of a dream. Mountains like those of Monument Valley, trees shaped as if cared for by a somewhat crazy gardener, endless plains: the landscape recounts the astonished stupor of the characters’ inner reality. A landscape that, like them, is, on the one hand, enigmatic and perennially changing, but in the long run, it is also always there and obstinately true to its essence, just like the characters.

In the 1970s, one of the most influential Japanese comics in history, Kozure Okami (“Lone Wolf and Cub”) by Kazuo Koike and Gōseki Kojima, recounts the adventures of a disowned samurai, who leads the paradoxical life of an assassin who also strictly respects the ethics of bushido.

Kozure Okami (“Lone Wolf and Cub”) by Kazuo Koike and Gōseki Kojima, 2001

Although Kozure Okami can, strictly speaking, be defined as an adventure comic, it is also a masterpiece of psychological subtleties and unpredictable narrative virtuosities. Here, the landscape plays a role that is traditional in the visual arts of the Far East, where the representation of the place has always been designated the task of transmitting what one does not want (or cannot) say directly. There are endless (and beautiful) sequences of cartoons in which the protagonist does nothing but walk in the nature of the Japanese Middle Ages, and even the inevitable armed fights are always located in environments that are not difficult to recognise as symbolic.

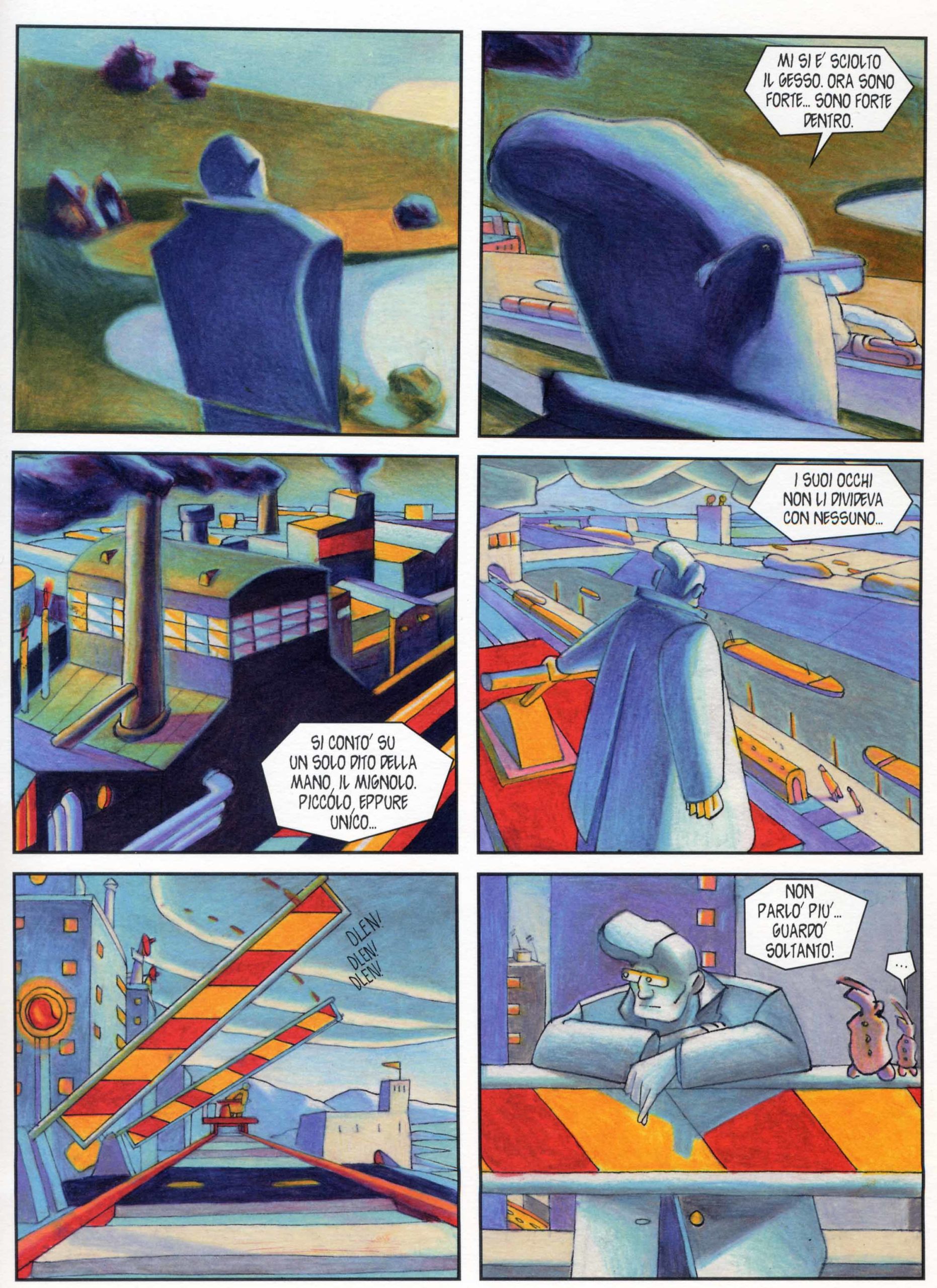

In 1982, the landscape is the absolute protagonist of Lorenzo Mattotti’s Il Signor Spartaco. Spartaco is a dreamer, and the story travels between reality and dream. Spartaco is often lost in contemplation, and what he contemplates is the landscape, whether natural or urban. What he sees is what he is, inwardly, in that moment.

Il Signor Spartaco by Lorenzo Mattotti, 1982

In 1984 Mattotti produced one of the comics of the century: Fuochi (“Fires”). The protagonists are the battleship lieutenant Assenzio, and the Island of Sant’Agata. Over the course of the story, Assenzio loses his consciousness within the landscape, in its dualistic form: bright, delicate and sunny during the day; extreme, painful and dotted with fires at night. Not only does the landscape express an emotional state: the landscape is that emotional state. The landscape is the whole Island of Sant’Agata that breathes, expressing all that is emotional as opposed to the rational rigours of military life.

Fuochi by Lorenzo Mattotti, 1984

From this moment onwards in Mattotti’s work, emotionality and landscape will be practically one and the same thing. In the title of his first black and white graphic novel, L’uomo alla finestra (“The man at the window”) (1992) there is already a direct reference to the gaze upon the outside world, a gaze which is, at the same time, directed towards one’s inner reality. Here, the same thin line of the nib draws people and things; characters and landscape are one.

The approach of Oltremai (2013), a non-narrative series of plates made with ink brush, is even more extreme. Here, there are only landscapes, with small recurring human figures that traverse them. There is not even a story anymore, and the work itself is difficult to classify as a comic strip. It is just as difficult to classify it as an illustration (because it does not illustrate any text) or as a painting (because of its multiple nature, and the techniques and materials used). There is a series of highly emotive moments, all related by the same inquietude, and conveyed by a fantastical dimension that’s entirely based upon the landscape.

Oltremai by Lorenzo Mattotti, 2013

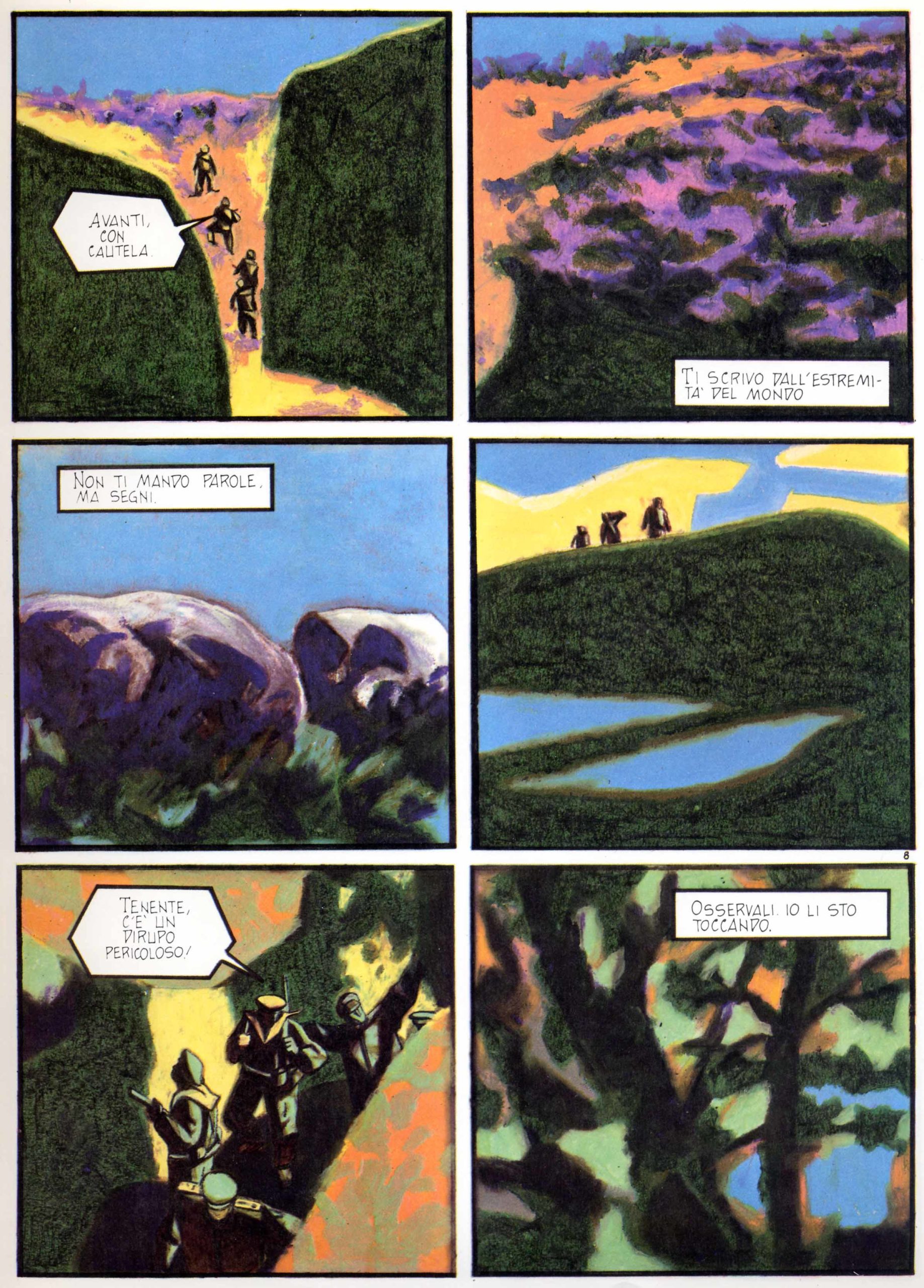

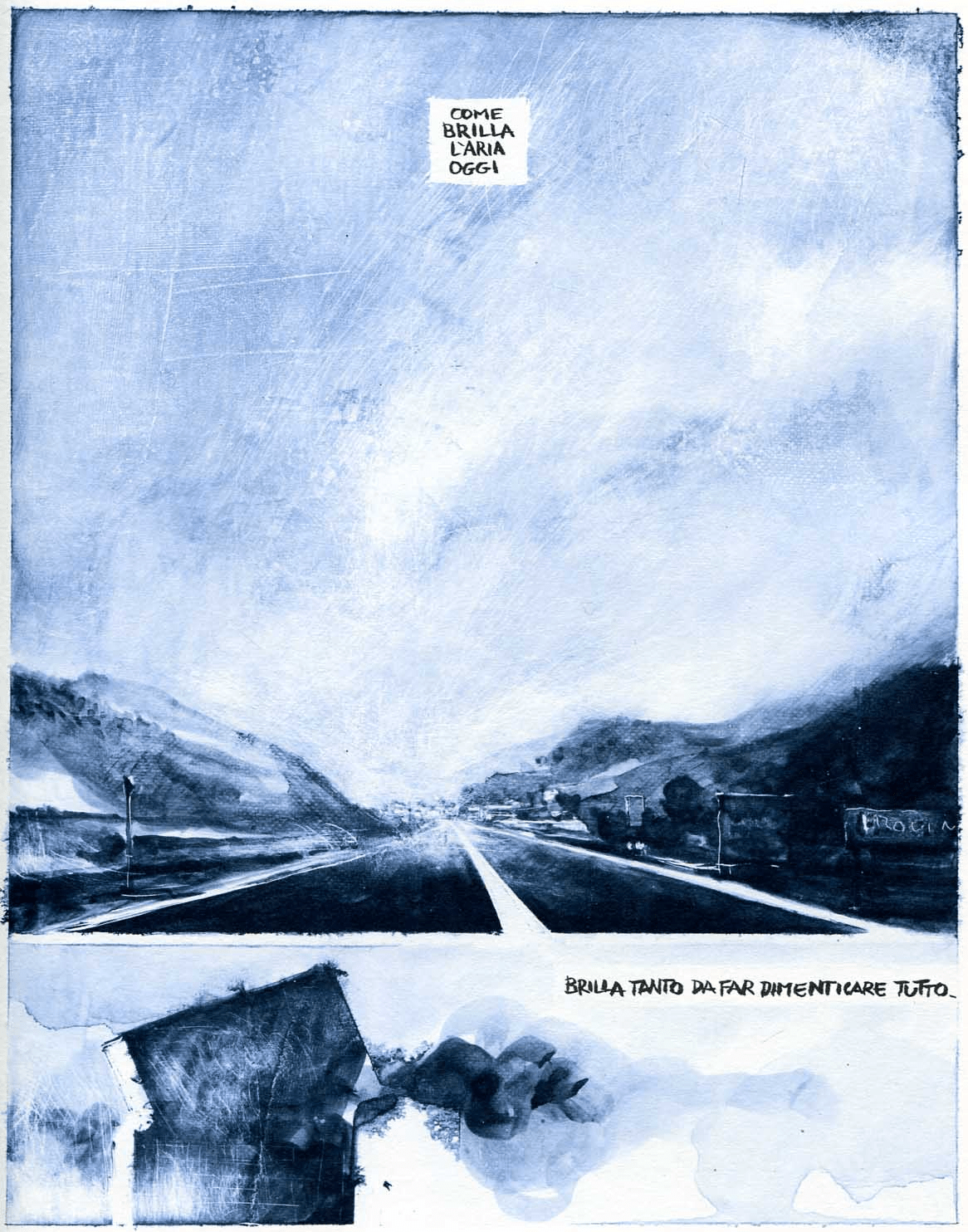

In Italy, Gipi is amongst those who have followed Mattotti’s path. The author opens his first book (Esterno notte, 2003) with a large landscape, almost a full page. In contrast to what the landscape seems to be starting to tell, the first story of the book, La storia di Faccia (“Story of Face”) opens instead, with a character addressing us coarsely, taking centre stage and rejecting the apparent pathetic fallacy of the landscape. Gipi’s inspiration is much closer to realism than that of Mattotti, very often leaning towards the autobiographical. Yet the landscape plays a similar role in both authors’ work, transmitting what words cannot (or do not want to) say. Much more than words, the landscape, even when evoked graphically, is able to envelop us, transforming the normal façade of images and words into an immersion that is musical, and emotionally captivating.

Esterno notte by Gipi, 2003

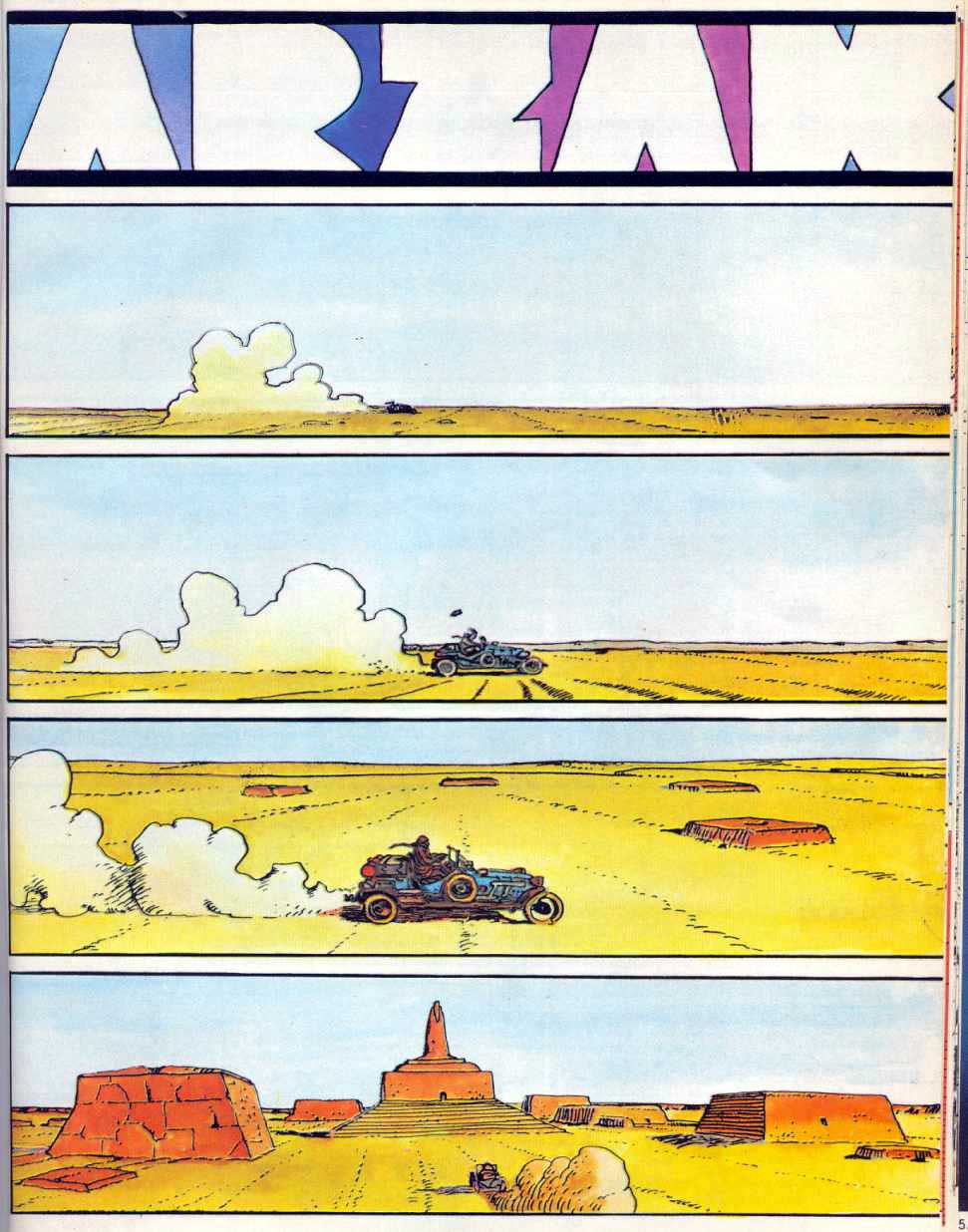

The publishing house Les Humanoïdes Associés noticed this immersive value of the landscape as early as the 1970s, when they began to publish their stories deliberately without traditional narrative structures (because, as Moebius said in an interview in 1974, a story need not be constructed like a house, with a door to enter and a roof to cover it; a story can be made like a cloud, in the shape of an elephant or giraffe).

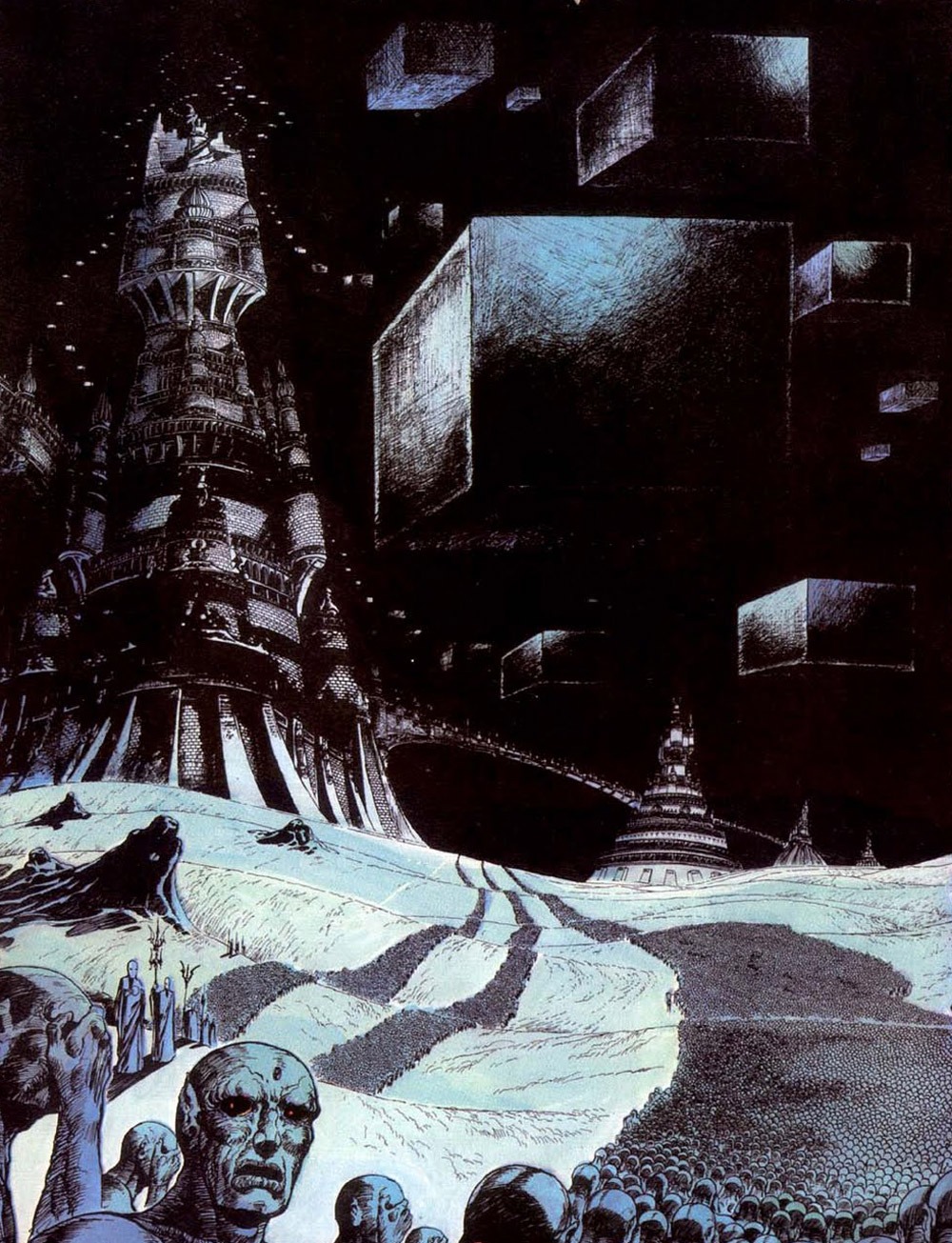

Moebius and Druillet were acutely aware that the science fiction theme is little more than an excuse, employed to gain freedom. To play with large landscape images allows one to configure the comic text as a series of immersions into different emotional and engaging tonalities. What remains of the story, is only as a tension that takes us towards an understanding that is often de facto denied, while the suggestive power of the sequence of images does the lion’s share of the work.

Yragaâl by Philippe Druillet, 1971

Even if the anti-narrative extremism of the Humanoïdes did not gain direct followers, and Moebius himself soon returned to the narration of real stories, the emotionally spectacular dimension of the landscape remains a characteristic of many French comics. We find, for example, traces of this (but also traces of Gipi, I would say) in the beautiful Blast, by Manu Larcenet (2009-11). Here, in the tradition of Georges Simenon’s detective stories, the story itself seems to be in search of a story. The landscape is as unclean and poignant as the unbalanced but very sharp protagonist.

Arzak by Moebius, 1975

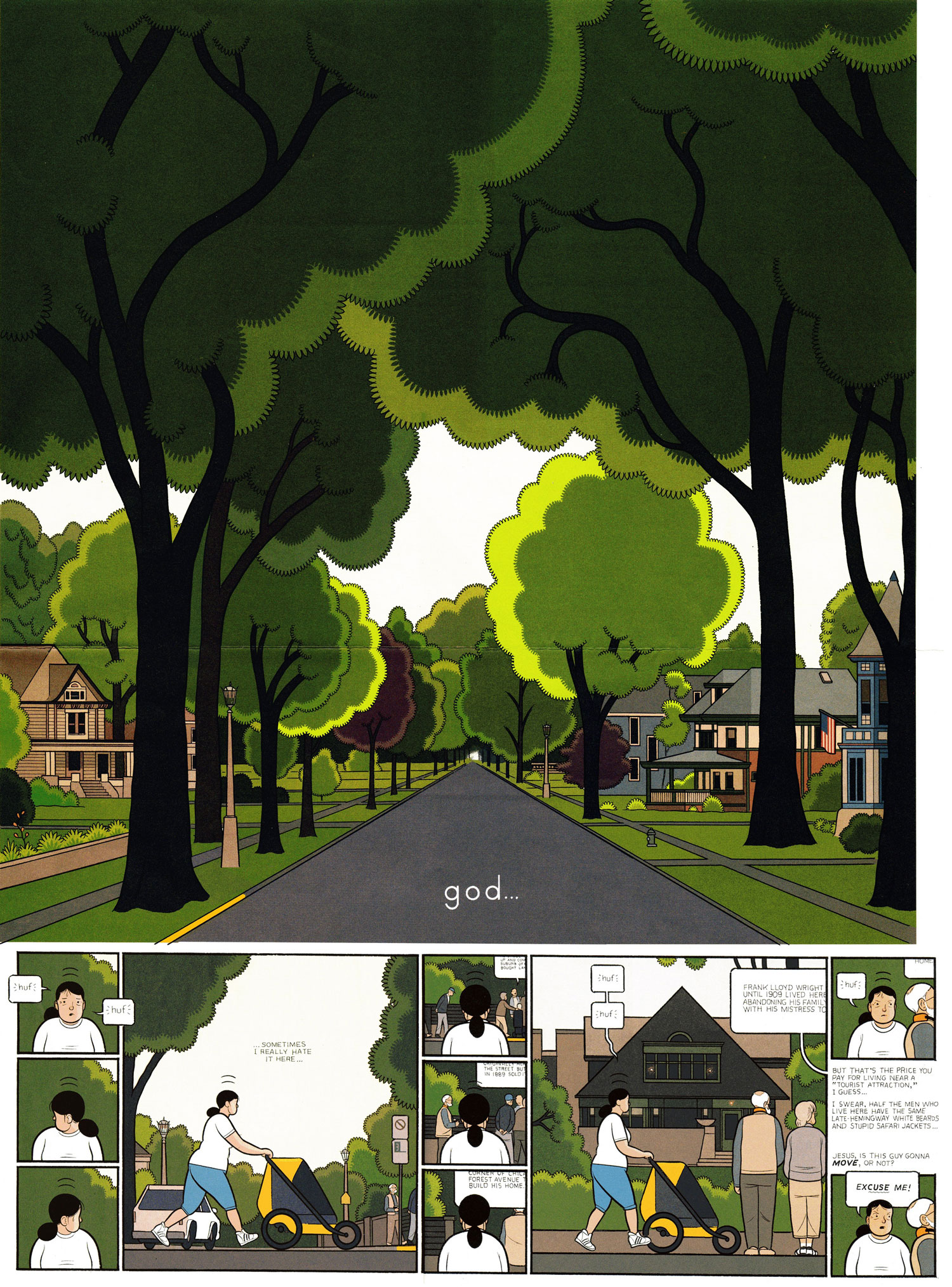

The emotionally expressive role of the landscape that characterises contemporary comics manifests not only in warm authors like the ones we have talked about so far but also in the seemingly chilling work of, American, Chris Ware. Ware has an extremely regular, almost geometric signature style, which often becomes exactly geometric when it comes to rendering buildings.

These are always shown in an axonometric view – never, that is, according to the rules of the central Renaissance perspective. This obsession with order also involves the architecture of the pages, which are made with meticulous precision and a proliferation of large and small or very small cartoons, always characterised by an extraordinary and disturbing elegance.

Building Stories by Chris Ware, 2012

The stories that Ware tells are not far from those of the minimalist tradition: stories of small lives and frustrations, shown with accurate and merciless precision as if they were insects under the entomologist’s lens. But the sensation of detachment that may be delivered by these scenes is only apparent because under this surface of coldness there is a whole world of desperately agitated beings – and they are evidently us. Even in Ware, the landscape plays a crucial role, because it is just as cold, geometric and inhuman as the appearance of those lives.

In his relationship with the landscape, Ware makes his own tragic conception of life evident, because his protagonists are prisoners of it, just as the ancient heroes were prisoners of their own destiny. The landscape is the immobility of the world around us, neither beautiful nor ugly in itself, but certainly enveloping: a condemnation for eternity, we should say.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »