City without morals

One of the main protagonists of Italian radical architecture, multidisciplinary artist and researcher Ugo La Pietra has dedicated his life to the understanding of the power relations embedded into our modern cities. He has seen the city of Milan change considerably over the years, with the development of new neighbourhoods, new technologies, new forms of daily leisure life. But the power relations that inform these structures remain, perhaps even more concretely and yet paradoxically harder to grasp. Starting from the series “City Without Morals”, this article is a reflection on the contradictions of the Lumbard metropolis and the ways in which these can be revealed and challenged.

In the past, and still today, I could not help but express the discomfort that I feel within our repressive society. My research on what I called the “Disequilibrating System”, which I began to develop in the mid-sixties, is the perhaps most evident expression of this unease. Varying in its outputs, from drawings to interventions taking place within the environment itself, the “Disequilibrating System” consists of a series of aesthetic operations that aim to reveal the existence of those predetermined schemas that, by organising the space around us, influence our daily lives without us being aware of it. In the meantime, the system also offers opportunities for rupture within this organised structure.

Indeed, compared to the generation of the sixties, who found it conceptually difficult to produce work within this system, my position was not, and still is not, that of refusing to operate within this type of society (at the time this was called “self-castration”), nor that of escaping it (utopia). Rather, I have always attempted to create with an attitude of critique. The goal is to decode and unveil the mechanisms which through the space are organised – whether it be private or public – and how this organisation is always a physical expression of power.

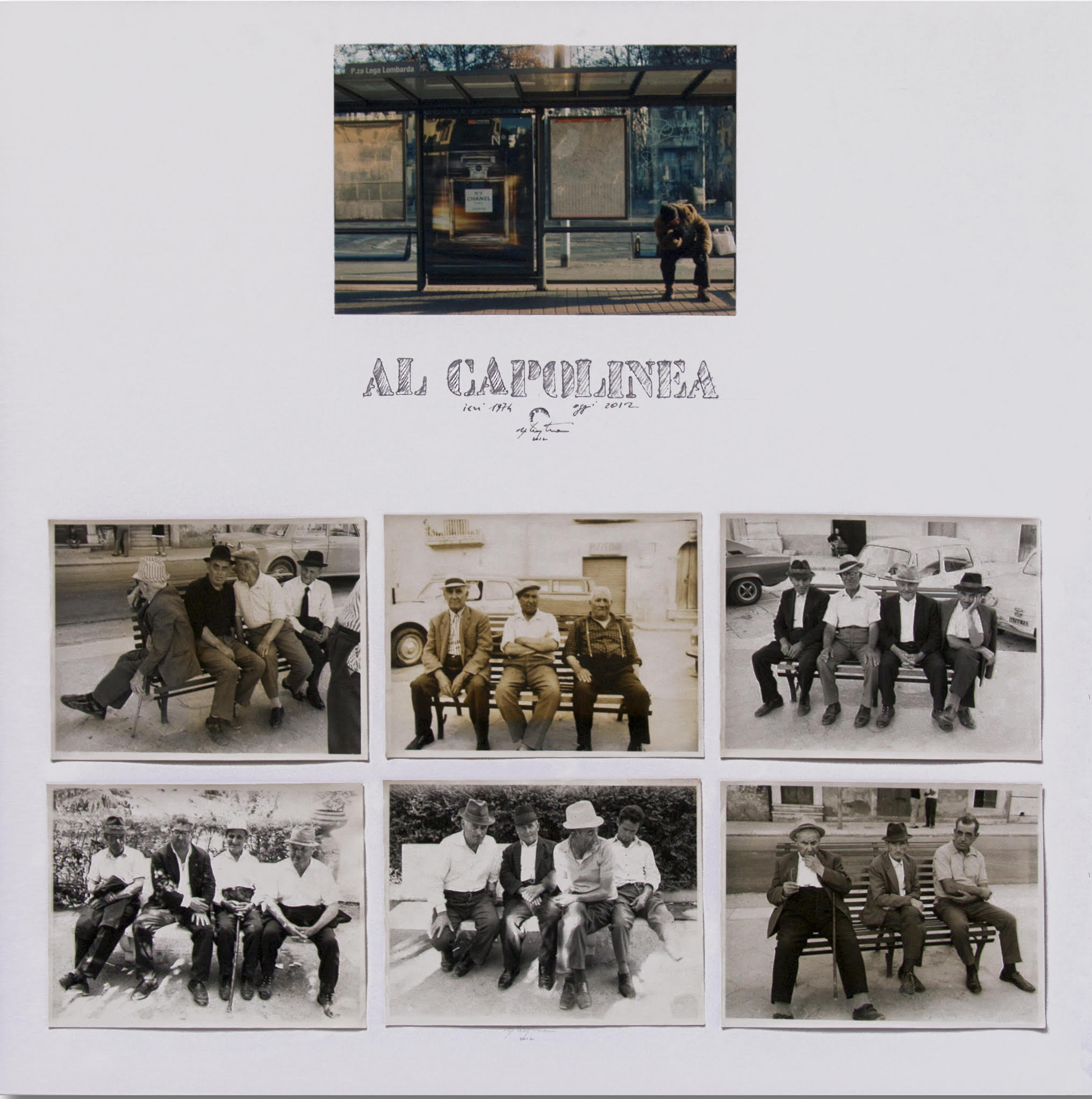

Reflecting on the space which we inhabit also means looking at those possible “rare” expressions of freedom (“degrees of freedom”) that I was able to find in the urban periphery, where the system was (and is) less efficient. Since the late 1960s, I carried out urban explorations, tracking phenomena such as the “preferential itineraries” – those pathways that emerge from the repetitive walking of inhabitants – or the urban gardens that lie in the shadow of Milan’s dormitory blocks, created by reclaiming discarded industrial objects. These were and still are concrete examples of individual expression that ruptures the behavioural regimes imposed through the urban environment.

From these first urban analyses, further reflections and side-projects have sprung up, all directed towards reclaiming the collective space. “To live is to be everywhere at home” is the slogan that summarises all my research and is still relevant today. Thus, all my works, from the sixties to today (whether they be drawings, paintings, performances, films, videos, publications…) have been and continue to be conditioned by the outside world, by what surrounds me: by everyday life.

My works respond to the contradictions of our society. For example, the films and appliances that are part of the work Telematic House (exhibited at MoMA in New York in 1972 during the exhibition Italy: The new domestic landscape) served to highlight the existence of an “information and communication system” which, in those years, still had to be liberated from its restrictive nature through the use new technologies (anticipating what would later become the internet). Today, I am interested in new urban models: the “Gazebos”, for instance. I am designing these in order to overcome this exasperating urban pressure: excess noise, excess people, excess pollution, excess traffic, and so on.

So, it has been some time now that I have maintained that the environment in which we live, being an expression of our society, must be intervened upon. The physical environment represents the ideal field of experimentation and it is, therefore, an “art for the social” that I believe we should be practicing.1 We cannot forget that the so-called physical environment is simply the formalisation of a whole series of contradictions that exist within our society. To give an example: for more than thirty years, a huge urban population (ranging from 16 to 40 years old and more) spends many hours of its time, from 7 pm to 4 am, in the urban space. Many people who get together “to be together”. In Italy, they gave this phenomenon a Spanish name, the “movida”. I have written extensively about this behavioural phenomenon, which I described with the phrase “we live in crowded solitudes.” It is a phenomenon that, in the last few decades, has affected the behaviour of an enormous mass of urbanised individuals, conditioning the city space accordingly: bars and restaurants grow exponentially and the use of space is modified to the point where we have created new forms of pollution – from noise pollution to traffic emissions, and so on.

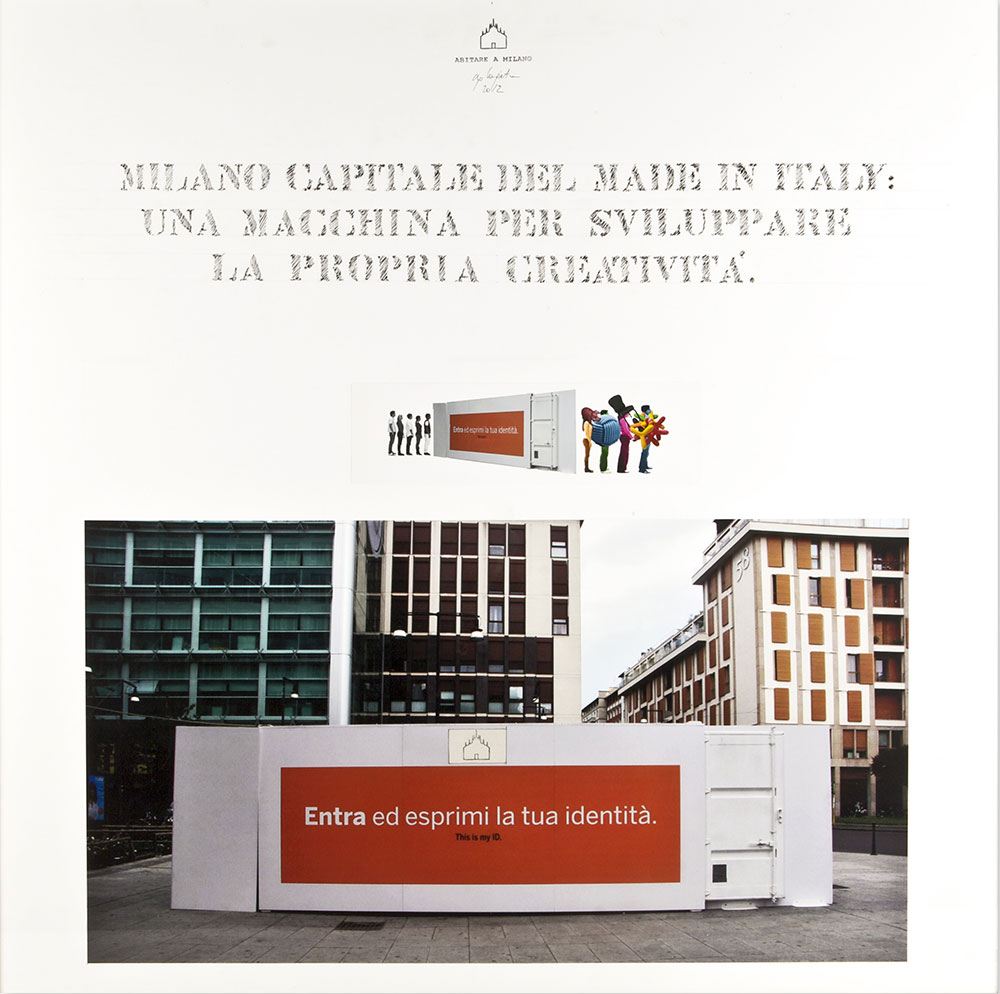

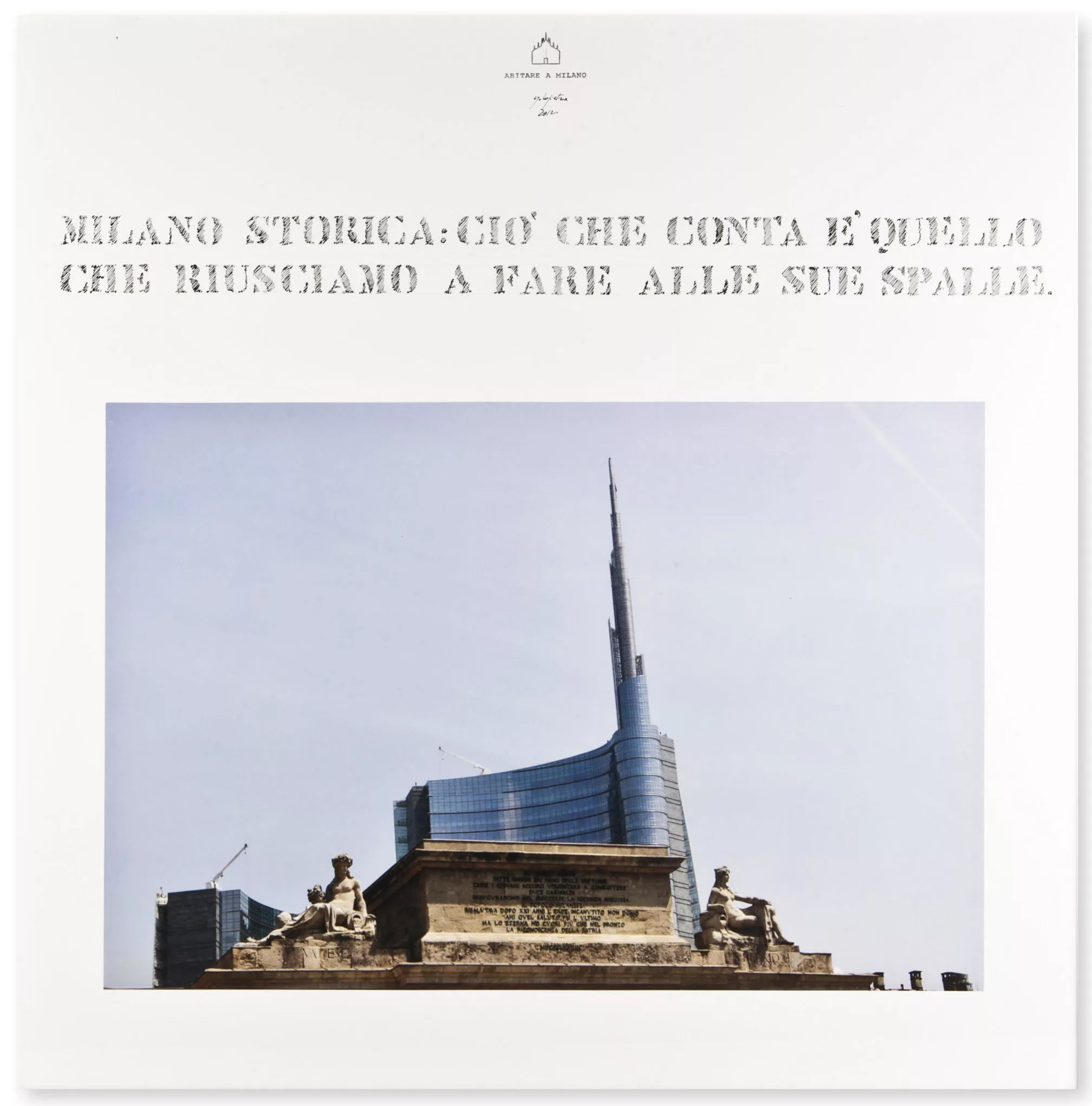

The “City without Morals” arose from similar reflections. This is a series of works in which the dialogue between photos, collages and texts attempts to express the contradictions that the contemporary city increasingly expresses. As the introductory text to the project explains: “The city ruled by decisional and operational structures is by now organised through a range of systems, inside which the relation between the decisional levels of political-economic interventions and the basic social context is expressed by mechanisms of coercion of the social group’s real needs and aspirations. Day by day, we lose more and more our ability to recover meanings and values in the urban scene, where our eye sees only signs, to which we automatically adapt our behaviour.”

The peculiar moral authority that consumer society is able to assert over the population forces us to do an activity, where all creative behaviours (individual and collective) are banished. The city grows in a chaotic way: for the urbanised people, the city is a mix of rambling relations; whilst for city planners, it is made up of codified maps; for the policeman, it is a collection of crimes confirmed by radio reports; for traffic policemen, the city is a network of underground cables connecting all television cameras to their “headquarters”; and for the politician, the city means many votes.

The “City without morals” is a city that transforms a pedestrian island into a parking lot for vehicles that supply goods daily to wholesale stores located in the centre of town (see the example of Via Paolo Sarpi in Milan). The “City without morals” is a city that has as its flagship cultural project the “Fuori Salone”, where anything can happen! The “City without morals” is a city that allows (for economic interest) the construction of a ridiculous little garden in Piazza Duomo – the most important and iconic square of the city. I could go on and on!

The more the city without morals advances, the more it transforms the relationships between individuals and social groups. In Milan, you rarely saw people in the streets (everyone was working); today Milan is an open-air restaurant. Artists used to meet in specific bars (the Giamaica or the Genis – we can see them in the photo taken by Uliano Lucas with Fabro, Vigo, Ferrari, Manzoni, myself…). Today, there are hundreds of thousands of artists in Milan, but often they have never met each other. In the past, the city was home to extended families and strong local communities. Today, the family structure is increasingly fragile, many are single and neighbourhood relationships no longer exist. Under the forces of capitalism and globalisation, the city increasingly consists of isolated individuals, living precariously without the structural and emotional support that the city once provided.

These are not “nostalgia-laden” beliefs, just brief observations that are enough to demonstrate the city’s profound cultural and social transformation.

Footnotes

[1] See “Art for the Social” in the 1970s, up to the 1978 Biennial.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »