Apnea

Glimpses of images, by nature marked by constraints and boundaries: the time and space that you might capture during apnea diving. In this photo-essay, Gianluca Tesauro reflects on his own experience as a freediver and on the idea that, as humans, there will always be something that we cannot access.

The act of holding one’s breath. This is the universe that fascinated me during the lockdown. It intrigued me to learn more about apnea and the feeling of transcendence that it generates in those who practice it.

I had just begun diving when we were forced to remain in our homes. As the sea was denied to us, even for those still within its reach, I attempted to find that psycho-somatic state on dry land. It wasn’t long before abysses and whales, sportsmen and photographers became my isolation companions. Lying on the carpet and breathing deeply served as a means of escape, a path to a mental and therapeutic blue that motivated me to cope with the day ahead. It is one of the few benefits of enforced isolation: you have to find the best way to be alone with yourself.

In order to practice apnea diving, you must be in a state of stillness. It requires a profound mental focus on breathing as our vital act. By exploring apnea, you are patiently searching for an inner world that cannot be accessed if you rely on scuba equipment. In scuba diving, the body’s breathing capacity remains very similar to that which we experience on dry land.

At all latitudes and at all times, the world has known stories of human beings with extraordinary diving capabilities: the Urinatores of ancient Rome; the Japanese pearl fishers Ama, literally “sea women”; the Bajau, Indonesian sea nomads. And yet, much like scuba, apnea diving became a recognised sport only recently.

Over the past few decades, when the first freediving championships were established, mythological humans were summoned back into existence. Crossing limits previously believed to be physically unattainable became scientifically possible. Freedivers rewrote science by relying on physical capabilities alone. They proved that Cola Pesce is not just a legend.1

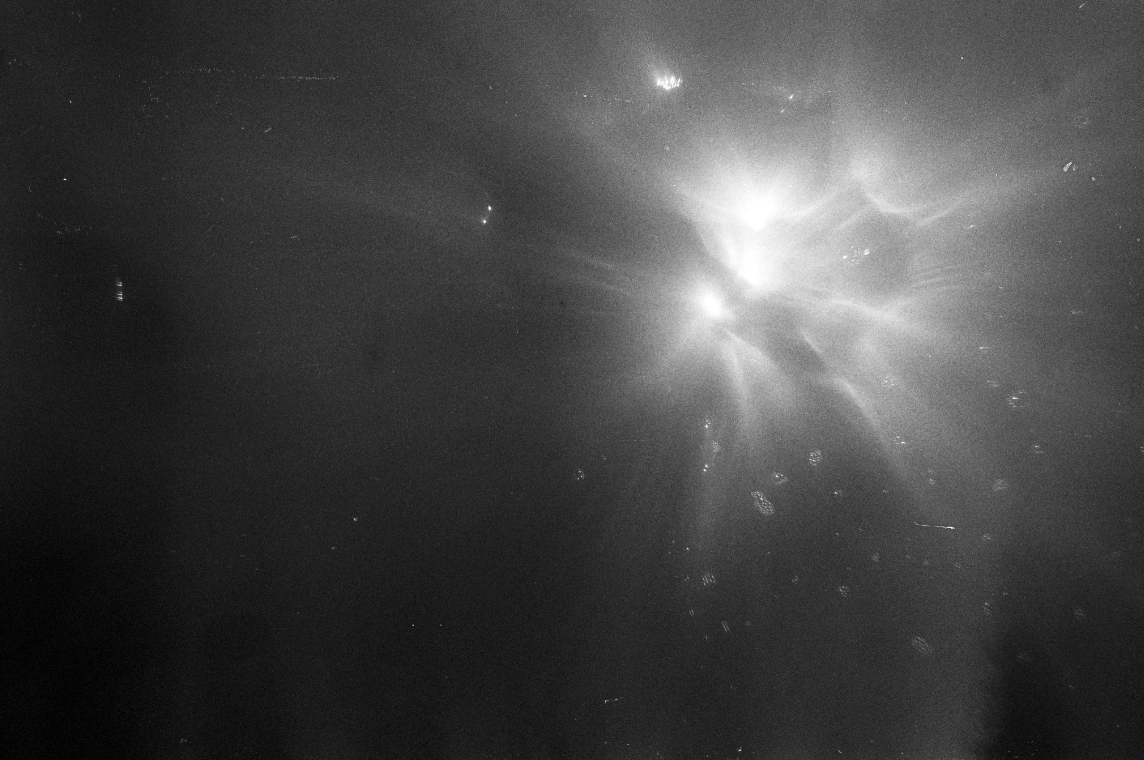

In one of the documentaries that I would watch to escape solitude, an athlete spoke about the effect of surfacing from the depths. Apnea diving is a dangerous and thrilling activity, in part due to the visions that sometimes occur due to the absence of oxygen during the dive. So you see, it isn’t really even about the sea.

Take the swimming pool. When I practice there, the only thing animating the submerged surface is a blue line. At first, I asked those who have dedicated their lives to this activity: what makes it so enjoyable? What makes it so worthwhile, if you cannot confront the sea depths? As they pointed out, the experience is internal.

It is to do with the fascination of reaching a physical and mental limit. There are those who jump into the void, and those who run at high speeds: the freediver suspends his breath, challenging his mind not to fear the absence, to then return to the surface unscathed.

I was born and raised on the Amalfi Coast. In the years that I lived far away, the absence of the sea was a source of constant anxiety for me. My horizon was lacking. Once I returned home, I bought my first wetsuit. But I soon realised that I was not interested in hunting games. I wanted instead to inspect the submerged world, and, through reflection, discover myself within it.

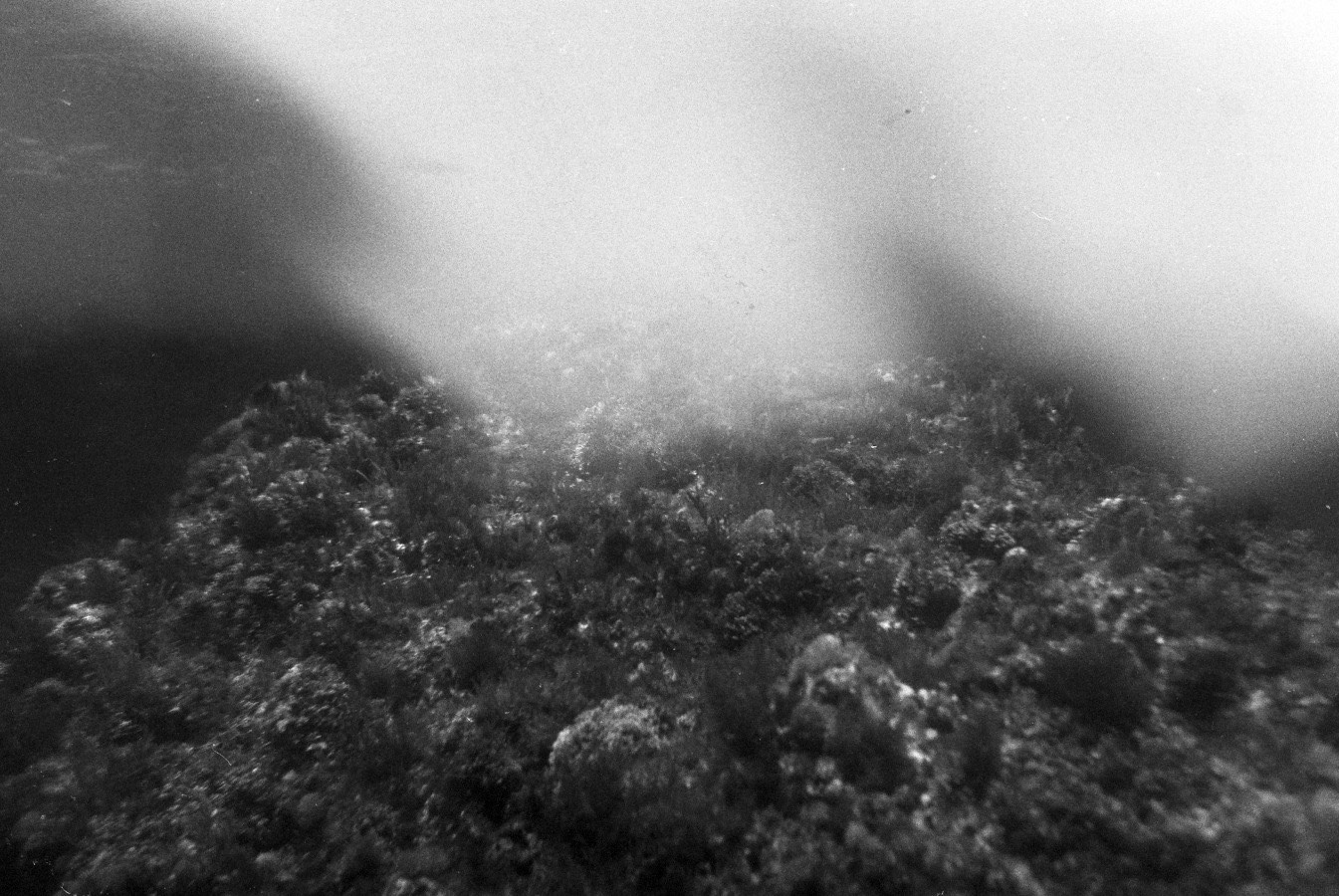

We are visually familiar with everything that appears on the surface, but what lies beneath this threshold? What form does life take there, where everything was born? As soon as the lockdown was over and I was free to return to the water, I began to take photographs. I steered clear of automatic cameras, but neither did I buy fully professional equipment. Instead, I purchased a Nikonos IV – an old amphibious analogue camera produced in the early days of underwater photography. I was fascinated by having a technical limit, something that would echo the physical one.

Most of the sea’s depths are unknown to us and the current state of our understanding of them is limited. We can go and return from space, but just a few steps away from our beach umbrellas is a world that we hardly perceive. A world that, for who knows how much longer, is still a mystery. We can observe, trace, and study the animals of the sky and of the earth. The world of fish is still, in part, only theory and imagination.

The distance between us and this world is evident. The act of immersion alone, our body’s ability to slow the heartbeat when immersed in water, is sufficient to communicate how this place indicates our true origin. The air causes us to forget our amphibious nature, which remains dormant within us.

Analogue photography is now back in fashion, but we’re hardly used to it, let alone photography underwater. Not only here do we have no immediate visual representation of the result, but in order to take the photo we must look through the viewfinder while wearing a mask – perhaps even a misty one. In face of this uncertainty, we would be tempted to shoot the same scene several times. However, the limited number of shots per reel forces us to be sparing, also because during a dive there is no time to change rolls of film.

These cameras are designed for scuba diving, which grants stability and longer timeframes, as well as the possibility of using auxiliary lighting equipment. Attempting to use them for apnea diving may even sound pretentious. For me, however, this experiment gives every single photo a specific significance. There is almost a personal desire not to abandon possibilities. At this moment in time, in which I am still learning to dive underwater, documenting my experience with such a limited and unpredictable means allows me to re-access it for what it was – an aimless, adventurous and dreamlike dimension.

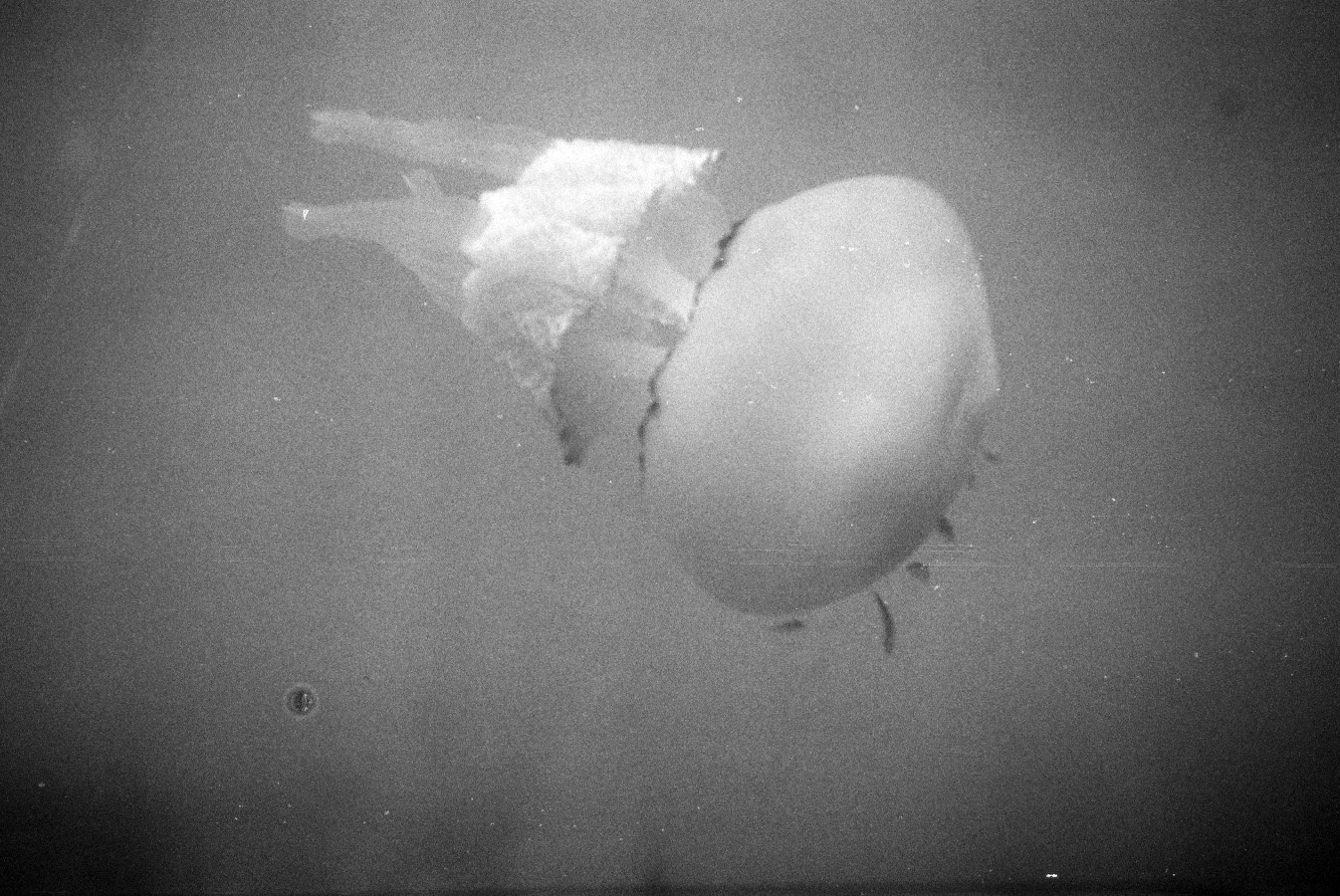

Similar to spearfishing, which is only legal when carried out during apnea diving, apnea photography follows similar rules. In order to capture a fish in its natural environment, you have to be on equal footing with it, thus trying to remain lucid even if it drags you into its depths.

Underwater, pressure plays a crucial role. Being comfortable in an alien environment requires considerable effort. A sea creature of even the smallest size appears to be far more advanced than we are. The body’s physiological adaptation to extreme environmental conditions alters the perception of the world around us. We enter another universe. Everything appears bigger, imminent, impending; colours fade as depth increases: red disappears, then orange, then yellow, until the entire vision is dominated by a deep dark blue. No sense of smell exists.

It is a set of minutes dominated by the unknown. As much as I can, I enjoy crouching at the bottom of the sea, waiting for life to resume. Watching a small fish approach me curiously, exchanging a glimpse, finding myself empathising with the other. Watching the approaching roof of water on the ascent is perhaps the most powerful image of any dive. Waves of light and salvation.

I can say I have experienced ecstasy and amazement, in every dive, even at modest depths. But the immense darkness is also frightening, as epitomised by the sea monsters of ancient legends and modern cinema. Fear, happiness, unconscious attraction, the amniotic fluid that overwrites our notion of being alive: this Big Blue is our own inner depth.

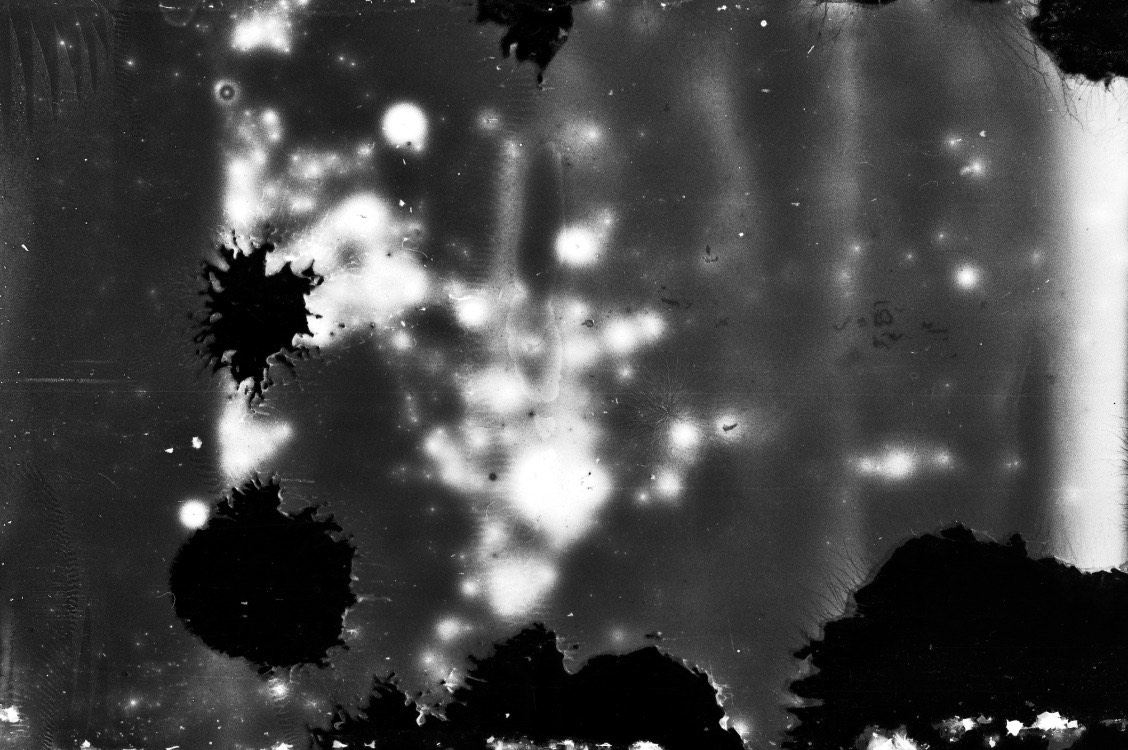

I bought two of these small cameras made of iron and seals. It seemed sufficient to me. Yet we, dry beings, do not realise that every grain of salt and drop of water has a weight in the sea. Because of my carelessness, I let water leak into both, one in Procida and the other in Erchie. Luckily, I was still able to develop their films.

The result is two sets in which something has been imprinted. The images that the sea gave back to me are not what I expected, nor what I believe I saw during my dives. It nevertheless illustrates how much we underestimate what we believe we know: there are no reliable images, but only glimpses of an accumulation of life, which like the sea is unpredictable, unexplainable, and infinite.

Footnotes & references

[1] Cola Pesce is a Sicilian legend about a merman, mentioned in literature as early as the 12th century. Born as Nicola di Messina, Cola Pesce was nicknamed as such because he was a great swimmer who could hold his breath for long periods of time when diving, eventually transforming into a merman after a challenge from the King of Sicily.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »