Forced to leave Italy due to his political activity, artist Pietro Marubi sought refuge in the town of Shkodër, Albania, where in 1856 he founded the first photographic atelier of the country. The hundreds of thousands of photographs produced by Marubi and his sons over the decades became the property of Hoxha’s regime in the early 1950s and were only made accessible to the public in 2016 when the collection was finally transferred to the Marubi National Museum of Photography. For their project The memory of the air, artists Chiaralice Rizzi and Alessandro Laita conducted research within this immense archive, recovering and discussing old photographs with the people connected to them, thus intercepting memories suspended between narration and silence.

Memory believes before knowing remembers.

Believes longer than recollects, longer than knowing even wonders.

William Faulkner, ‘Light in August’

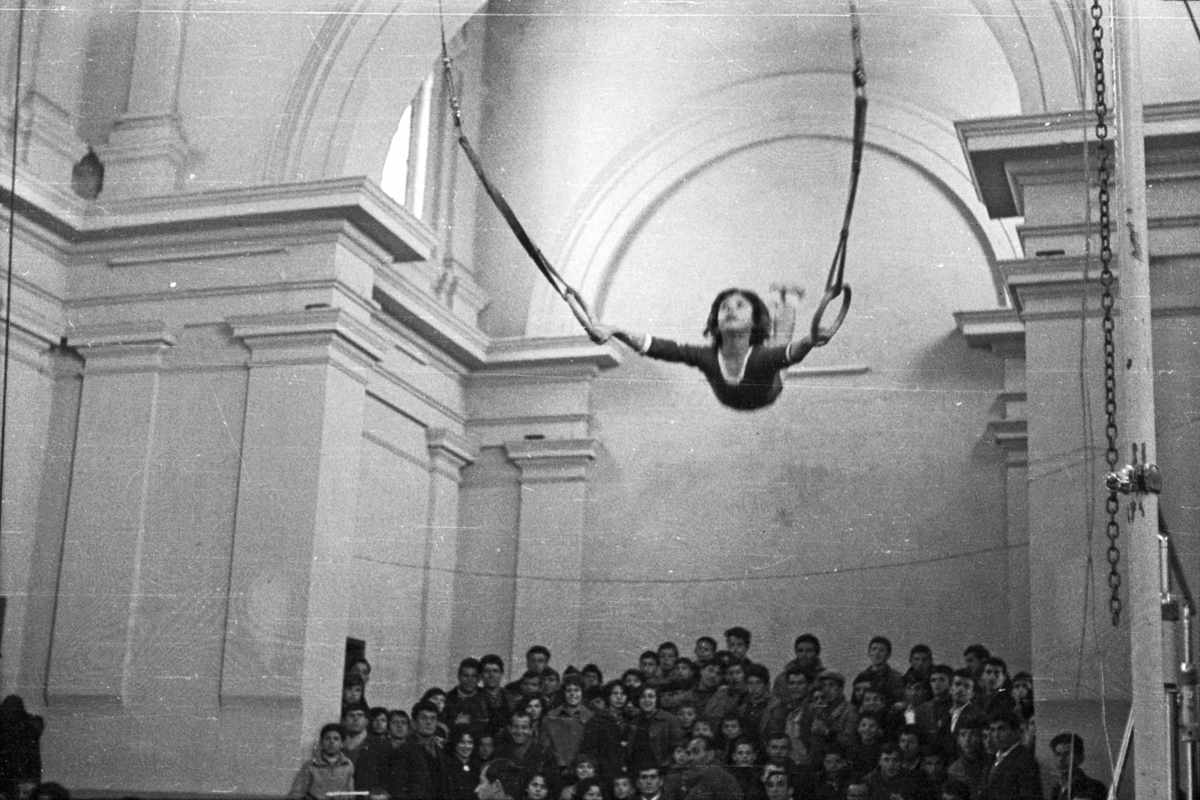

A single image brings others to mind. Invisible yet vivid, they spring from her story, filling a void. Natasha speaks, and in speaking she gives us the opportunity to finally appreciate that photo, which we saw for the first time in the archives of the Marubi museum. It is the photo of a slender girl, alone, concentrated and astonished; her body arched, compact, transmuted into angel, looking over the edge of the deconsecrated church’s vault.

That little girl is now a woman, the same one who tells us her life story starting from that very picture. It is a morning of September 2019, in a Tirana café; but the picture generates memories, even of what never was: the dream, shattered by Hoxha’s regime, of pursuing a career as a competitive athlete. We thus remain suspended between fundamental dialectics: desire for freedom and suffering constraint, hope and regret, lightness and gravity. In revealing itself, the image mutates.

Natasha’s story is the first of many that we would record over a period of five weeks, starting on the 20th of July 2021. They were very hot days. Meetings could only happen early in the morning or towards the end of the day. During one of the very first evenings, we walk with Stella, our friend and guide, to Leopold’s house, near Rruga G’juhadol, in the centre of Shkodra. Strolling through this city, you find interludes of sleepy quietude alternating with the lights of commercial establishments belonging to an indefinite time, the pleasant sound of passing bicycles, barking stray dogs retracing their trajectories.

We enter Leopolod’s house by climbing some steps. The brass-coloured walls of the entrance hall show paintings and relics of unfamiliar lives – far away, different, still alive. We don’t know it yet, but this evening, in his home, the informal ritual that will accompany almost all of our meetings will be inaugurated; a ritual that consists of offerings, stories, silence, listening, a desire for knowledge.

After having been received in the living room, we move to the kitchen. Leopold takes a small wooden object, shapeless and half-hidden, from a nail on the wall, accompanied by the pink reflections of the many copper utensils around it that have, in the interim, caught our attention. His hands hold the object intimately. We are not surprised when he explains that this concave piece of wood, a simple spoon, is the same one that had fed him during his life in prison. He was 17 years old then and had been accused of being an enemy of the people because his brother supported a party against the regime of the time.

The Italian that he speaks with us was learned in prison, as he found himself in the company of the Albanian intelligentsia. When they saw that young man, so alone and so lost, they told him to turn that experience into an opportunity, that is, by learning something every day. So he did, and with that language he acquired in the solitude of prison, before taking his leave he told us: “from every family you will visit, you will hear sad things. Everyone has a story to tell that is sad. History has not condemned the Italians as it has condemned us. You cannot understand. But it is natural not to understand.”

His words were full of truth. Only those who immerse themselves in Albanian history, and, in particular, that of Shkodra, can understand how much it seeps with suffering.

The following are but a few glimpses into the complexity of these stories, each sparked by the power of an image assumed forgotten. Every person we met had their eyes turned back towards their past, but their minds faced forwards: from the memory of times of oppression there is the will to redeem and regenerate, the will to narrate, as a way to assert – “I exist”.

The past never slips away. It is trace, symbol, starting point. Memory becomes a body, carrying its past as spontaneously as one holds a spoon.

◊ ◊ ◊

Alma Bazhdari Naraçi

Shkodër, Albania, 2021

Alma’s father, photographer unknown © Marubi National Museum of Photography

A photograph that has always been very important to me shows my father, who had escaped from the concentration camps at Pristina.

All people, in their own way, think of their father as handsome, but mine was truly gorgeous; he stands out in every photo for his beauty and way of dressing.

As a child, I was struck by this photograph because unlike the others, here I saw my father looking sad, shabby, skinny, with a ruined suitcase. Next to him there is a man I don’t recognise, I think they did not even know each other. At the age of 19 my father was put into a concentration camp at Pristina, and he was saved by an absolute stroke of luck. He was in a group of people being taken to a place where they would be executed. My grandfather saw this, understood the situation, and ran to the guards, asking them how much it would cost to spare his son.

He paid the requested sum and my father was removed from the group and left to wait in an office, where he could hear the sound of the gunshots that killed his friends. Only later did I understand that this story had tormented him throughout his life. By the time he had reached the age of 90, he was living with me in Italy; perhaps he felt that he no longer had anything to justify, he would leave our house and go to sit at the bus station, asking passers-by: “Would you like me to tell you a story?”

Or he would go to the park in front of the house, and as soon as he saw someone sitting there, he would begin to tell them about the time when he was 19 years old and he was rescued from the Nazis, when he heard his friends being shot. When he was very elderly, his eyes would fill with tears as he told the story, and I understood that he had been traumatised for his entire life by that event, and he could no longer bear the weight from which he had tried to shield us. The pain had transfigured him so badly that when he returned home my grandmother didn’t recognise him, and when he appeared at the door she asked him who he was.

During the four months spent in the concentration camp, my father not only lost many kilograms, but also the light in his eyes. A mother can recognise a son, no matter how wasted he is, but upon his return my father was so full of despair, so gutted, that not even his mother could recognise him. He fled definitively from the camp at the end of the war. He knew that the war was over when he saw the Germans abandon their weapons and run away as fast as they could.

I keep this photograph in my part of the house. On the back you can see a note he had written by hand, which says: “I returned from the German concentration camp, where in four months I lost 19 kg.” I often work with foreigners, and a German fellow I met left his own note, which is simply the German translation of the original phrase. It is interesting that he felt the urge to put it into German, and when he asked me if he could do it, I didn’t hesitate to give him permission. This photograph is the one that struck me most in the family albums, so I decided to keep it with me.

Alma’s home. Photo by Chiaralice Rizzi and Alessandro Laita

◊ ◊ ◊

Ahmet Shurdha

Shkodër, Albania, 2021

Ahmet’s family, photographed by Geg Marubi © Marubi National Museum of Photography

Take a look at this. I still have memories of Marubi from my childhood. My father corresponded with various people abroad, and they were curious to receive photos of our family. Friends were particularly eager for images.

After much hesitation, it was agreed that it could be done. Such reluctance was typical among people who had experienced persecution and did not want to take such a risk. When it was done, in fact, people made malicious comments: “Ah, so you’re still alive? You want to show off in public?”.

When my father told me we were going to have our picture taken, I was filled with joy. From that visit to Marubi’s studio, I remember how delicate he was, his courtesy. We entered through a door on the lower level, climbed the stairs, and as soon as we entered we were greeted by Geg Marubi. I remember how happy he was to see my father again; they were old friends, and on that day they had a long conversation. I noticed the fine curtains in the studio, placed behind the photographs, and I remember the camera, covered with a black cloth.

He began to position us: those who were seated had a stool, while the others stood up behind them. I was again struck by his extreme politeness as he arranged us for the shot, accompanied by phrases like “if you please,” “be careful,” “please be patient,” “we’ll do this right away,” “just a bit longer.” He said: “Mr. Shurdha, allow me, may I move the lady, just for a second, there, all done.” It was the first time I had seen such thoughtfulness, and I have never forgotten it.

Geg Marubi spoke with you, chatted, he had an absolutely special manner, and given my age I was able to observe this kindness over the years. Taking pictures of individual subjects is definitely easier, but his tactful courtesy was rare, and in all honesty I can say that he was a Catholic of bygone days, a man of culture, and I believe that like anyone who had had a chance to travel a bit abroad, this was noticeable. I don’t wish to boast, but my father died an Austrian. At the age of 14, his father sent him to Vienna for his education. For one year he stayed with an elderly lady, a custom that still exists today. Then he found a place of his own, he went to college, and my grandfather tried to cover all his needs.

This is why I say Marubi was phenomenal: to manage to achieve those goals, for a person who had not gone beyond elementary school, is no small thing. And it is absolutely true. The relations between Catholics and Muslims were extraordinary. Many times, they have asked me to talk about the relationships we had with Jews and Catholics. Besides the value of the object itself, for me this photograph remains as a reminder of his courtesy. In the picture, here on the stool to the right is my father, Muhamet Shurdha, next to sister Fatbardha, while my mother, Nezihat Behri Shurdha, is on the left; in the upper row, you see my sister Vahide and me, Ahmet.

Ahmet’s home. Photo by Chiaralice and Alessandro Laita

◊ ◊ ◊

Romeo Gurakuqui

Shkodër, Albania, 2021

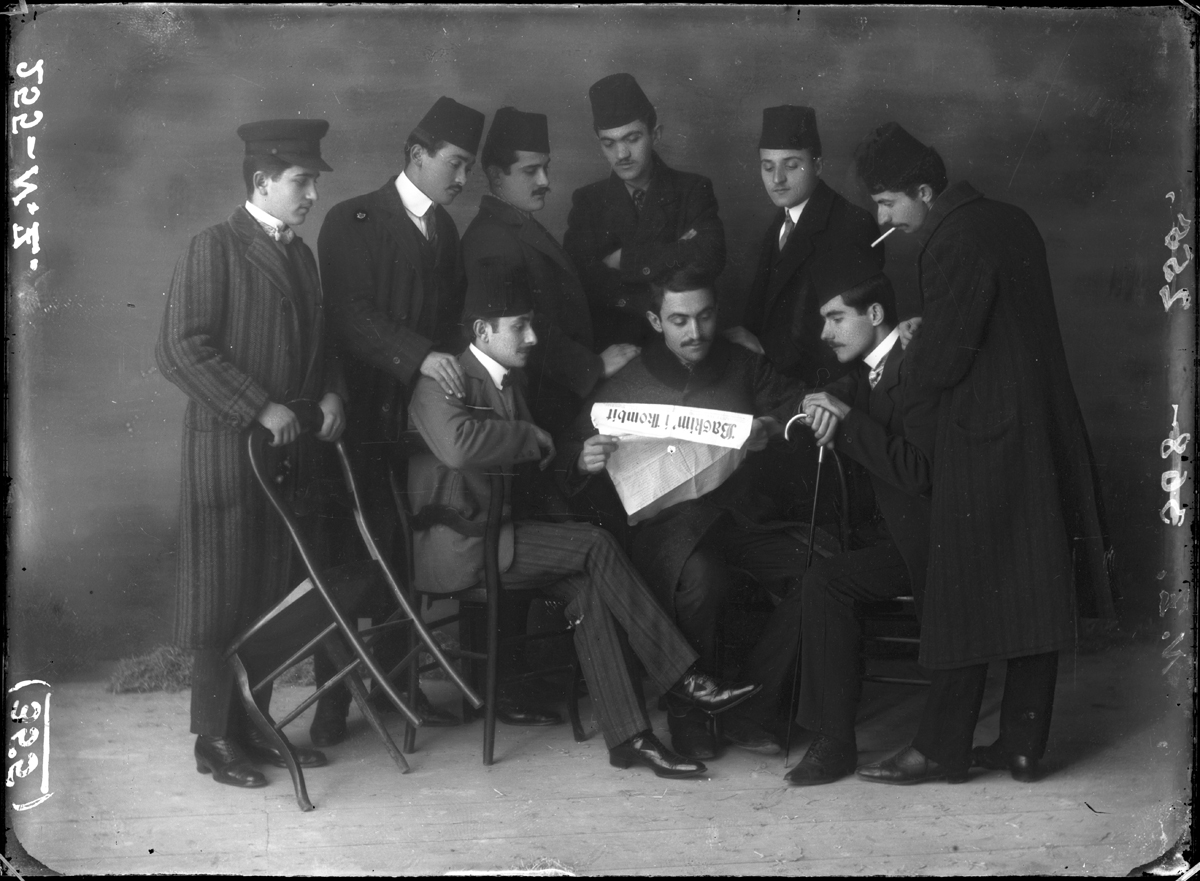

The founders of the Club of the Albanian Language, photographed by Pietro Marubi, 1908 © Marubi National Museum of Photography

This is a photograph of the founders of the Club of the Albanian Language, created in 1908.

After the Young Turk Revolution, the constitution of the Ottoman Empire, of which Albania was then a province, was revised. Teaching of the Albanian language and the formation of cultural organisations were permitted. The club was one of those organisations, created by some young men who had graduated from the Italian school of “Arts and Crafts” of Shkodër.

The club’s activity went through a short interruption whose dates I cannot indicate precisely, but considering the fact that the photo is from 1911, it was probably taken shortly after the resumption. Here, in particular, we can see the members reading the magazine Bashkimi i Kombit (Unity of the Nation), published at Monastir (Bitola), which is located in the south of the current Republic of North Macedonia.

My grandfather Lazër Gurakuqi worked as a correspondent for the magazine: in the photograph taken by Marubi he can be seen reading an issue to his friends. As you may notice, they always respected the rules of expression of identity within the Empire, wearing the red fez in public. My grandfather, in honour of an independent Albania, did not wear one. This detail was pointed out to me by my father, and even earlier by my grandmother, and it has stayed with me ever since then.

Here you see the board of directors of the Club of the Albanian Language. The charter was approved at the same time as the first assembly and the appointment of the board: the director Kel Kraja, vice-director Mati Logoreci, secretary Bumci, members Kel Koleli, Kel Marubi, Karlo Suma, and finally my grandfather, Lazër Gurakuqi.

I have always kept this photo in my home, in a smaller format, I must have it somewhere. The one you are seeing is an enlargement, which together with other photos of families in Shkodër hung in my studio at the European University of Tirana for eleven years. I told anyone who came to see me and entered my studio about my city, Shkodër.

The founders of the club were also the inventors and promoters of the Albanian National Library. The details of that episode have recently surfaced thanks to the recovery of all the documentation on the part of professor Aurel Plasari, one of the most brilliant and erudite minds we have in Albania today. With his research, he has shed light on the previously unknown history of the club of the Albanian language, and the documents indicate my grandfather as one of the people behind the idea. There is another detail connected with the transfer of the Library of the Literary Commission of Shkodër to Tirana. Albania prospered under Austrian rule.

In this florid period a sort of Albanian Academy of Sciences was founded, which for the first time contained a Literary Commission that brought together the finest intellectuals of the time, and Albanologists from abroad. One of the institutions under the aegis of the commission was a fine library. Initially located in a Shkodër, starting in March 1920 it was moved to Tirana, by order of Karl Gurakuqi. Its collection thus became the base for the formation of the present National Library in Tirana.

The story of the move narrated by Plasari is marvellous. We have to remember that all this was happening in the Albania of the 1920s, a backward country, without roads: it could take a few days to go from Shkodër to Tirana, and the road was in rather bad condition. At first the books found a new home in the library of the Ministry of Education, until the founding of the National Library through the initiative of Karl, who was also its first director, and had all the books moved into it.

Romeo’s studio. Photo by Chiaralice and Alessandro Laita

Credits

Opening image:

Angjelin Nenshati, ‘First Show at the New Youth Club’, 1967. © Marubi National Museum of Photography

Recent articles

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »

How many types of lightning are there, and how did the Victorians perceive and rationalise them? This article by James Broome, first published on The Strand Magazine in 1897, puts together photographs from both observatories and amateurs to show lightning in many of its different forms and shapes, while reflecting… Read more »

Venice is perhaps the only city in the world where food can only be delivered on foot. Recounting his experience as a delivery “walker”, Giorgio Pirina traces a fresco of his daily shifts, caught between digitalised work and timeless sites, with the liberating experience of walking contrasting with the impact… Read more »