When time lasts a ton

In 2019, the collapse of the Córrego do Feijão dam in Minas Gerais, Brazil, released a mudflow that left environmental and humanitarian devastation in its wake. Two years later, artists Bárbara Lissa and Maria Vaz returned to the zone to document the aftermath. In this text, they consider the limitations of the human perspective as a witness to the long-term effects of our agency upon the landscape, as well as the contradictions that often lie within extractivist notions of progress.

In January 2021, a fine iron ore dust hovered invisibly in the air of Córrego do Feijão, a district of Brumadinho, in the Minas Gerais state of Brazil. This dust is pervasive in several cities due to mining activity in the territory and it is so fine that it sneakily invades the body, contaminating the skin and lungs of those who live with it. Furthermore, as a result of mining in the state, by 2021, at least two rivers in Minas Gerais – the Doce and the Paraopeba – were dead, and two of the largest river basins in the state were contaminated. These are the least visible layers of mining. Only those who want to see it and feel it can actually sense it.

After all, how is it possible to prove that a body got sick from an invisible, undetectable thing? And how is it possible to know that a river has died? Yet all the other strata are clearly visible to the eye: the slicing of the mountains is not a subtle thing, and the landscape is shattered by this constant and accelerated activity. Even the cracks in the dams are not so well hidden. The grotesque is invisible only to those who don’t want to see it.

It is in 2021 that we, Bárbara Lissa and Maria Vaz, both from Minas Gerais, started this work. Exactly two years after the collapse of the Córrego do Feijão dam – controlled by the multinational mining company Vale S.A – which occurred on January 25, 2019. Although not the first, this was considered the biggest work accident ever recorded in Brazil, causing the death of at least 270 people, the disappearance of many others and the spillage of more than 10 million cubic meters of waste. The collapse left a trail of destruction along its way, contaminating the Paraopeba River, which supplies 35 municipalities in Minas Gerais. It was, and continues to be, a humanitarian and environmental catastrophe.

In 2019, the disaster was nationally and internationally televised, documented and commented upon. Four years earlier, in 2015, the world had seen a similar event occur in the city Mariana, also in the state of Minas Gerais. However, as if one disaster were not enough, even after the second one occurred – amounting to the death of 289 people, two rivers (home to thousands of fish and source of livelihood for hundreds of families), and an uncountable number of plants and animals – the mining activity in the region did not even decrease.

An activity that runs at a fast pace and that comes with many risks: of the 367 mining tailings dams accounted for in the state, 21 present medium or high risk to the surrounding population, and 148 have a high potential for damage to the riverside populations and their historical and cultural heritage, to the urban and rural infrastructure, as well as the environment.

According to the Public Ministry of Minas Gerais, this threat already existed at the Córrego do Feijão dam before the so-called accident, and this was known to the company.1 Mining in the state of Minas Gerais takes place in areas of environmental preservation, with river sources, intense wildlife of fauna and flora and close to communities. With predatory mining, little supervision, and licenses given even with the risks – also due to private interest and international pressure – the regions are exploited until their complete exhaustion.2 Then, the process starts again in another territory, for example, the state parks of Itacolomi and Ibitipoca, put up for auction in 2022 by the governor of Minas Gerais, Romeu Zema.

It is significant to remember that more than 300 years earlier, during the colonisation of Brazil, the Bandeirantes who explored the territory found gold deposits in the state of Minas Gerais, and the mining activity began – since then, aggressive and predatory to the environment and the workers. Over the years, mining has become one of the state’s principal economic activities. Nowadays, it is not just gold anymore but iron that drives this market. More than 300 years of history were built upon the exploration and maintenance of corporatist privileges, with the aim of profit, above all. Years of history were buried in the ruble of progress. In 2015 and 2019, even with all the spotlights and the vast reproduction of barbaric images that devastated Mariana and Brumadinho, some traces are already – practically – invisible.

A Estação (The station), 2022

Back in 2021, it is the invisible – or what one wants to make invisible – that takes us back to this zone in search of what still reverberated there since the day of the disaster. What could be seen, photographed and experienced two years after that January 2019? How could we create a memory of the unimaginable or even what seemed invisible? What would be the other ways of documenting disasters beyond the moment they occur, beyond the immediate destruction caused by them? From these questions, we decided to sensitively photograph what was still there to be seen in the local landscape, two years after the event – a desolate horizon and abandoned houses now covered by low plants and grass that hides the mud.

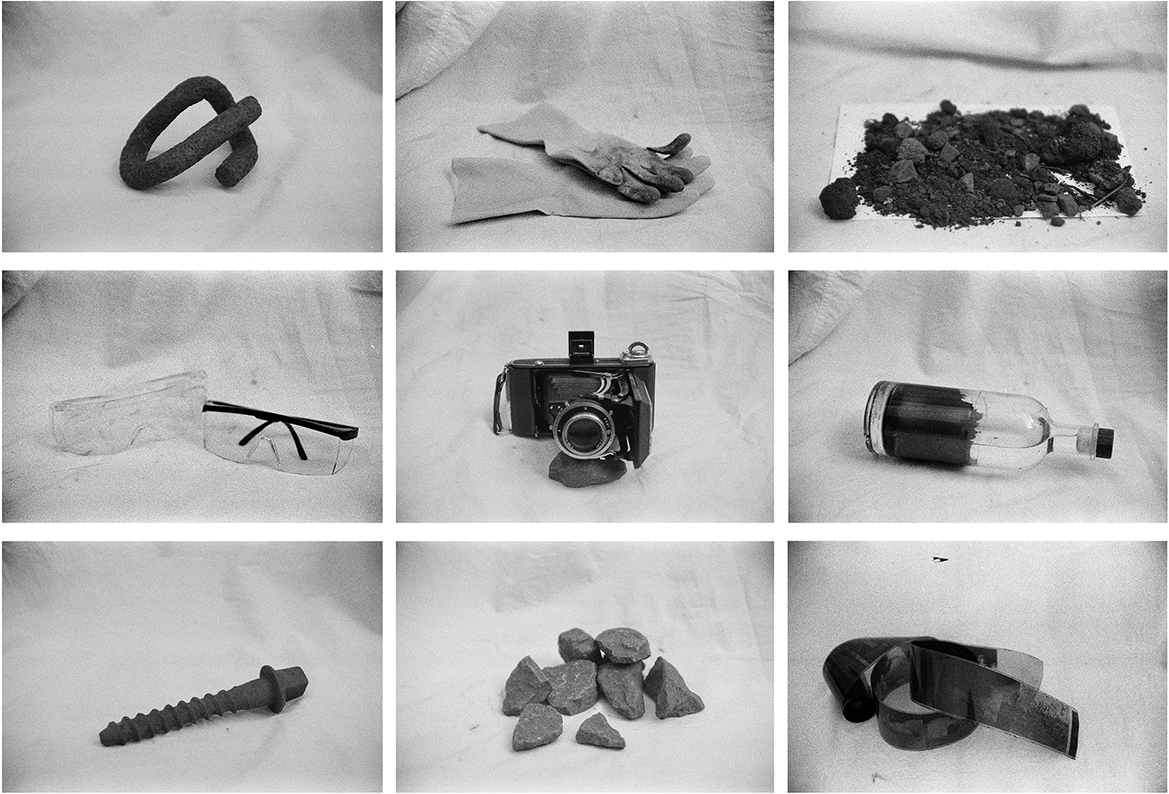

Through an experimental, documentary and imaginary way, the memory of that January 25, 2019, is recorded in photographs and videos, inviting us to look at it from the territory’s perspective; of the non-human beings who experienced and are experiencing a perpetrated domination and destruction. The visual work When time lasts a ton is composed of many layers that are difficult to access, without explicit references to the disaster, to trigger the memory of those who look at the images, remembering that the disaster continues to happen.

Using a Zeiss Ikon camera and a 120 mm negative, the photographs are combined without being separated by frames, giving materiality to the diversity of temporal dimensions. When working with a technique that allows for the production of a partial overlapping of images, where one frame invades and recomposes the other, it is possible to construct and conjugate many possible landscapes and times. This narration builds a different testimony of the event, focusing on what remains of it.

When time lasts a ton builds a narrative of trauma from the very materiality of the landscape present in the images: the materiality of the territory, the mountain, the ore, the river, the air, and the animals. The negatives were developed with the local water, contaminated by heavy metals and fine ore dust, resulting in ghostly images loaded with layers that make them difficult to apprehend. Ghosts are also a call to memory.

The work unfolded, in addition to the photographs, in two videos. In A Estação (The station) (2022), we witness the iron ore being taken from the mountains of Minas Gerais by the train that nowadays transports the ore, but that once also transported people along those same rails and stations. While waiting for the ore train, we met Crescêncio, a 70-year-old man who lives a few meters from the tracks in the Melo Franco district, also in Brumadinho. The city was formed by the construction of the railroad, which was a link between the community.

Tempo Partido (Broken time), 2022

After its deactivation, many residents left, and a large part of the local trade was closed, completely modifying the community. The station, once a place for passages and meetings, from where the train brought and took visitors and passengers, is now a vague memory of meetings and departures. Crescêncio and his neighbours breathe in every day the toxic dust that arrives with the 150 wagons transporting the ore every hour, all day, without rest. Even when it’s dawn, he runs and whistles loudly.

In the video Tempo Partido (Broken time) (2022), two times appear to coexist in the territory of Brumadinho after the rupture of the Córrego do Feijão dam: a still, silent time, suspended since the event, with a landscape that takes time to “digest ” the remains of the mud – and, above all, it is going through a pandemic – and another time that never ceases to run, by the grass sown to proliferate and replace the mud and, also, by the Vale train that daily transports tons of ore. Faced with the accelerated time of economic progress and the time of “failure”, the bridge broken by mud on the day of disaster reveals the ruin created by the progress itself. A storm that takes us unstoppably into the future, dragging us along while the debris accumulates at our feet before the march of progress that continues to pass over everything.

Footnotes & references

[1] Zisimopoulou, Documentos indicam que Vale sabia das chances de rompimento da barragem de Brumadinho desde 2017, https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2019/02/12/documentos-indicam-que-vale-sabia-das-chances-de-rompimento-da-barragem-da-brumadinho-desde-2017.ghtml, accessed on 15/12/22.

[2] Rafaella Dotta, MG passa por dezembro de pressão para aumentar mineração, Brasil de Fato, https://www.brasildefatomg.com.br/2018/12/14/mg-passa-por-dezembro-de-pressao-para-aumentar-mineracao, accessed on 15/12/22. See also, Sabrina Rodrigues, Retrospectiva: Rompimento da barragem de Brumadinho foi a primeira grande tragédia ambiental do ano, O-eco, https://oeco.org.br/noticias/rompimento-da-barragem-de-brumadinho-e-a-primeira-grande-tragedia-ambiental-do-ano/, accessed on 15/12/22

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »