Somewhere near the edge of Wales, in the Llŷn Peninsula, two gateposts stand in a nameless field. For playwright Kevin Dyer, these posts become the locus of a number of stories that interweave the lives of the local fictional community with the slow rhythms of an ever-present landscape.

Two ancient gate posts on a hill in a field in the far, far west of Wales. Inland is a mosaic of ancient fields separated by dykes and zig-zag single-track lanes. Out to sea, crystal-blue water stretching across the Cambrian Bay. If you squint you can make out Aberystwyth, Llangranog, maybe Barmouth, and then the curve of land all round to the far, far tip of Pembrokeshire. West, the coastal path rises to the serrated massif of Rhiw, which is an old Welsh word for hill. East along the coastal path is a slow slope down to Aberdaron with its two pubs, two shops, bakery and not a lot else.

The gate between the two posts and the walls either side have long since gone, but these two weathered uprights still stand. A pair of monoliths, in the far field.

The story goes, if one part of a couple has to leave – for war or work or famine or whatever – the door or the gate they left through must remain, no matter what changes are made to farm, field or dwelling, or they will never be able to find their way back to the hearth.

This old gateway is known locally as ‘Adref Non’ – the Home of Non. Non, a young wife with red hair and the palest of skin, with a tiny waist and hands that could wrestle a ram to the ground, walked out on her husband nearly two hundred years ago. It is said she left because she did not believe he loved her enough. But he waited, standing by the gate every evening apparently, hoping for her return, until he died 40 years later. He was buried in the field by the gate. Now his grave is lost in the grassland and just the old stone posts remain.

Sioned sits by the gates, wondering what the fuck to do. Not so much about the stones, she knows they should have been cleared donkey’s years back to give the tractor and bailer a clear run from the end of the track into this field overlooking the sea. They’re just an obstacle now, an inconvenience.

In the lea of one of them, a little prickly patch of featherwort grows. Its yellow flowers the first bit of colour up here on the wind-scoured cliff top. In the summer, on the sunny side a lizard spreads itself and lays its belly flat on the hot rock. Sioned sits still, as still as the stones themselves, nothing moving apart from her eyes watching the flick-flick of the lizard’s tongue.

Can the lizard smell her, the mix of farm-sweat and anger and bitter disappointment.

She should have smelled of Chanel, the expensive one, bought by her husband as an impromptu love gift. Davey had bought her that, the Chanel, when he and the lads went to Liverpool for the weekend, when he watched The Reds play, when he got smashed, when he went whoring and brought home the clap.

He tried to laugh it off, the itching on his dick, the red rash around and deep inside Sioned’s vagina, at first saying she must have got it from one of the sheep or something and passed it on to him. When he came out with that, she looked at him like Non looked at her stupid feckless husband for doing something equally stupid two centuries ago.

Non’s husband was a good man, a really good man. He didn’t drink, he didn’t gamble, he could read and do the farm accounts and fix the roof when the gales flicked the slates off and sent them spinning across the yard. But the daft bastard read the bible and believed every word and knew deep in his blood that the woman serves the man. He knew she listened to the snake at the beginning of time and they’ve all been paying for it ever since. When Non was sick during lambing he raged and raged; when she left the barn door open and the rats got in he kicked the dog till its ears bled. Non used to hide, flat on her face the other side of the stone trough at the back of the pig-sty. She’d lie, barely breathing, until her husband had spent his anger by kicking the door off its hinges or putting his hand through a window. But one spring morning when he found her and broke her jaw because three of the hens had gone to the fox, she walked through the stones, didn’t look back and that was that.

For generations daughters and granddaughters all the way down the line to Sioned have sat by the stones and wondered whether Non walked across the grass and turned right along the cliff track and then into Aberdaron where she caught a cart to god knows where… or whether she walked across the grass and took a left down over the cliff edge, and that was that.

The water down there is clear as glass. Sioned looked down and saw a seal one meter under, its tail and flippers spread out. It was half mermaid, half angel, basking in the August heat. The sun splintered through the clouds, coming down like fingers.

Sioned still itched at the bottom of her belly, at the top of her legs. It still burned when she went for a piss. Better now though, much, because of the antibiotics from Doctor Williams the local GP.

She wanted a lady doctor, when she went, last Tuesday, but she was off sick, so Doctor Williams it had to be. He was fifty-ish, chapel, married, a good man.

She didn’t mind the personal examination, at least he wore gloves and it was over pretty quick, but she did mind that when she went to the shop on Thursday to get a few things for tea that there was a sudden quiet, then a snigger.

When Lewis who loads the shelves and who was in the class below Sioned in secondary school saw her, he slapped his hands together.

Sioned didn’t get it, so Lewis did it again, looking straight at her with a big beam of self-satisfaction on his face.

‘Don’t you get it?’ he said.

He did the same again. The sound filled the shop.

‘Clap, see? Clap.’

The woman on the till was new, the girlfriend of someone who runs a campsite the other side of the valley. She laughed and Davey loved that, a woman laughing at his joke.

Sioned got it too, felt her face go hot, knew she was red from her neck up.

What to do? Brave it out? Tell Lewis that he was a moron and the reason nobody ever went out with him at school was his overwhelming body odour and the rumours about his penis?

‘It’s just a joke, Sioned. Can’t you take a joke?’

She looked up from her feet, flicked him a look.

Dr. Williams must have told someone who told someone else who told someone else, and so on and so on. Or maybe he’d written on the prescription the letters STD, just to let the pharmacist have a giggle.

Sioned saw Lewis rub his tongue round his mouth. She didn’t know what it meant, him doing this, except maybe he was tasting her pain, or salivating with this power he had over her. She dropped the potatoes on the floor. And the jar of Branston pickle. And the milk. The potatoes scattered, the jar splintered, the milk bottle split and the white stuff made a lake which she stood in the middle of.

Lewis stopped laughing.

‘What the hell?’

She gave him the finger and left.

When she get home Davey had turned the heating on and made the tea – all it needed was the pickle to go with the fish fingers, the potatoes for the chips and the milk for the hot chocolate he’d promised her on the sofa before bed. He was going to peel the potatoes and slice them and deep fry them. He was making amends. He knew they couldn’t have sex until the antibiotics had done their stuff, but maybe after the chippy tea she would dress up and they could watch something a bit porny on Netflix.

She stood in the door. No shopping.

‘Where’s the stuff?’

‘In the fucking shop.’

‘How can I do chips with no spuds?’

‘Everybody knows. Thanks a lot. I’m going for a bit of fresh air.’

It wasn’t cold but she knew it would be later, so she kept her coat on. She could feel her purse heavy in the pocket. She held it. Sioned left her bag though, the one with the two days of clothes that she’d packed the night Davey told her about Liverpool. For the last couple of weeks, it had been sitting in the bedroom on the chest of drawers. Just sitting there. Davey asked her when she packed it what it was, she said it was her bag. He asked what was it for, she said, ‘What do you think?’

She looked at her feet, there were splashes of milk and Branston Pickle on her jeans.

She looked at his face, then his hands. He was clearly agitated.

‘Later.’

She opened the door into the yard.

‘You can’t just walk out, you know, we got a farm.’

Pause, long pause, as she bit her bottom lip and felt the sick rise in her stomach.

‘And I got you, cariad, and you got me.’

It lifted up into her throat, it tasted of acid and loneliness.

‘And we’re gonna have kids, we’ve talked about it.’

It came higher, into her mouth, and she swallowed it back down.

She said, ‘We’ve also talked about going over to dairy and buying a static and doing holiday lets and you painting the back pantry cos the lime’s peeling off, but none of that has happened either.’

‘I’m grafting 24-7, Sion’. I’m not a let-down, I’m not.’

She looked at him with a face of granite.

‘What was she like?’

‘Who?’

‘The woman in Liverpool.’

‘I dunno.’

‘Course you do.’

‘I was pissed worn I.’

‘What was she wearing?’

‘I dunno.’

‘Dress? Jeans? What sort of bra?’

‘Christ knows, I wasn’t looking.’

‘Had your eyes closed did you?’

‘No.’

‘What then?’

He looked at the wall. He punched the wall. She didn’t flinch.

‘Was she pretty? And if you say not as pretty as me I’m getting my bag from upstairs and I’m off mate.’

‘She was brunette, that’s all.’

‘Name?’

‘I don’t know, you don’t ask the name do you?’

‘I don’t know, Davey, I’ve never… been in that situation.’

Sioned thought about who she hated most. Him, the woman, Doctor Morgan, Lewis in the shop, herself?

‘Was it a brothel?’

‘No.’

‘Where then?’

‘Round the back of a place?’

‘Place?’

‘Garage, I think.’

‘Classy.’

‘Not really, she stank of fags.’

‘Did you get your knees dirty?’

‘No.’

‘Standing up then.’

‘I can’t remember.’

‘Tell me, just tell me.’

He took a breath. He hated this talking nonsense.

‘I put my coat down.’

‘Proper gentleman.’

He sniffed, trying to be the tough man.

‘Didn’t you worry about getting caught? With your pants down? Behind a garage? In a busy city?’

‘The others kept guard.’

Silence. They stood there in the hallway.

At long last he thought the confession was all over and he could move them gently, if he was clever, back to normal.

‘It’s all right, the bloody tablets’ll clear it up in no time, then everything OK. It’s pretty funny really, us scratching at ourselves, me at my willy, you at your fou fou, innit?’

* * *

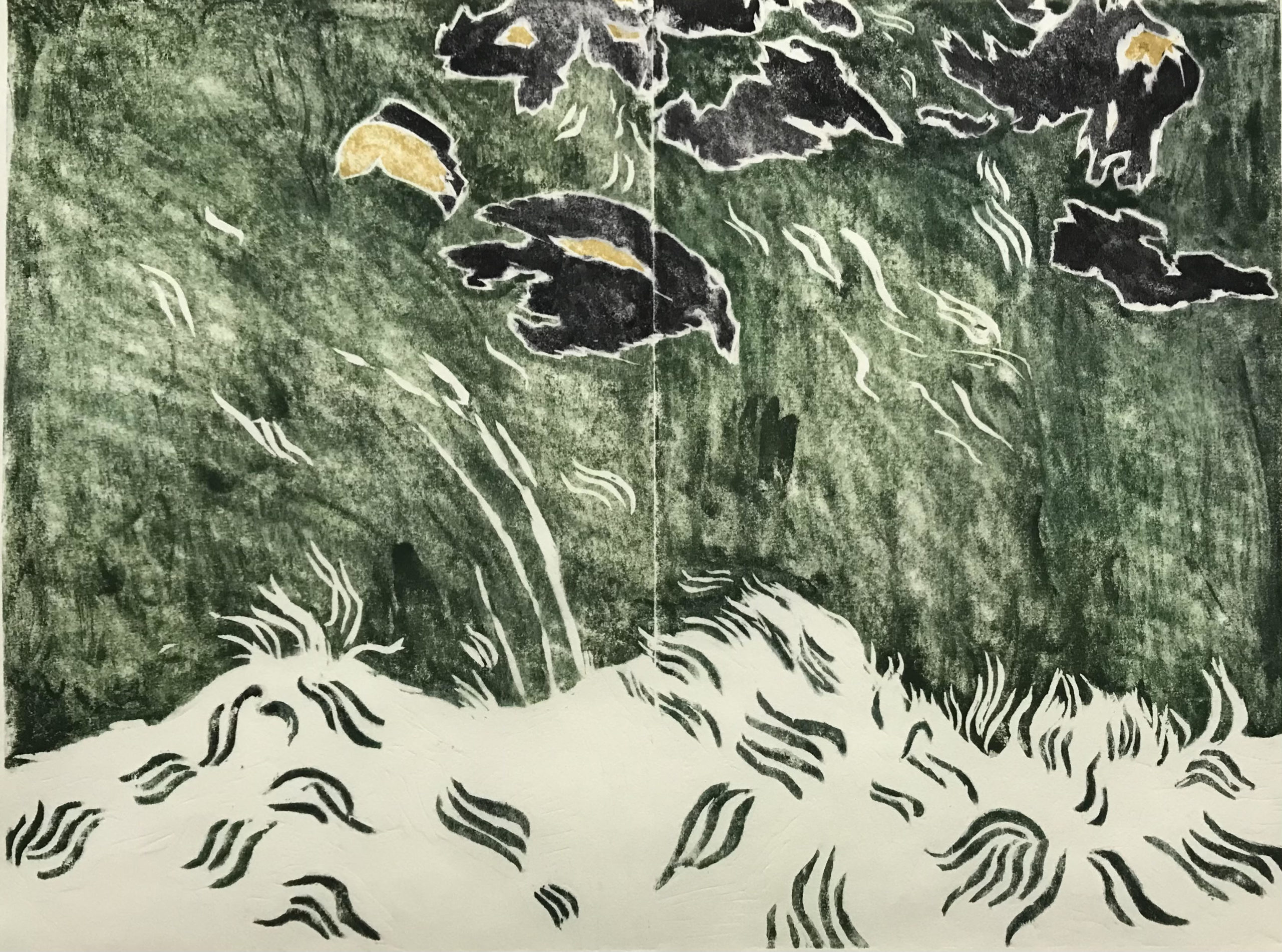

Now she was sitting by the two stones. Sitting by the stones in the most beautiful place in the whole wide world. The green of the grass, the blue of the sea. Her eyes followed the coastline all along to Ynys Enlli, the island, stubborn and dark off the headland. She looked at the bays and the rocky outcrops, she knew them all, could name them all, had swum, fished, climbed, rescued sheep, kissed her only boyfriend, done everything all over this place for 25 years.

She took out her phone. Who shall she call? Mam; Dad; Davey’s mates and tell them thank you very much, boys, Samaritans; coastguard, tell them there’s a woman’s body lying at the bottom of the cliff, she looks like she’s sleeping but there is blood from her head seeping into the sand?

Maybe she should phone Richard Richards, he’d always fancied her, all the time from primary when he used to borrow her pencil case. He left his at home on purpose so he could ask Sioned for hers. He used to send her poems, and he now works as a reporter on some big paper in London. Maybe he’d have her and they could stand side by side on the tube, their bodies pressing into each other, and their eyes locked. She still has his number. She could. She took a photo of where she was – two stones above the cliff and the sea glistening for miles and miles. She sent it to him on Whatsapp. One kiss, no message just the kiss.

The lizard had gone. She picked a flower then flicked it away.

She heard the dog barking in the yard, it was Davey the wanker coming out to look for her, to tell her not to be stupid.

She got up and walked fast into the sun. There were three hours of light left. She’d no idea what to do, none at all, but she was no fool, she’d know sure enough before the black came down and the sky filled with stars.

The two gateposts watched. They didn’t laugh, they didn’t smile.

They just waited, as they had done before,

for the next one.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »