The game

For decades, Patras has been one of the main hubs for migration routes to Europe, particularly Italy. A short distance from the inhabited areas and tourist facilities lie entire disused industrial sites occupied by migrants waiting to try their luck at “the game”, namely, illegally boarding westward bound ferries. The author provides a brief account of these places and their inhabitants, who are relegated to a state of perpetual transience.

The first thing one notices when arriving at the port of Patras are the very long queues of trucks, waiting to board or leave the ferries departing for the Italian Adriatic ports, mainly Bari, Ancona and Venice. Yet, this rather familiar image which can be found in many places around the world, hides an imperceptible but disarming reality, which, although subject to continuous processes of concealment, constitutes a paradigm of the current state of European borders.

Patras is located on the outskirts of western Greece in the region of Achaia. It is the third largest city in Greece after Athens and Thessaloniki with a population of around 200,000. As a result of its location and its role as a port city, it is known as the “Gateway of Greece to the West” and has always been a crossroads of trade routes to Europe. It is a place of transit – a borderland traversed by flows of goods and people as well as by migratory movements that ebb back and forth. First and foremost, Patras was an important departure point for Greek emigration to the United States, which in the early 1900s (1890s-1940s) saw up to 800,000 people arrive overseas, mainly for economic reasons related to financial and agricultural crises. Since the so-called “European refugee crisis” of 2015, it has been a key centre along one of the routes taken by people hoping to arrive in the European Union from Turkey, via Greece. For years, a constant flow of people – mainly from Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, but also Algeria and Morocco – have passed through Patras. Usually they arrive after having left the camps and reception facilities scattered across the Greek territory or having escaped border controls. They make their way to this city, from which ferries and ships bound for Italy set sail every day, in the hope of making it across the sea border.

An organisation called “No Name Kitchen” has been active in Patras since 2019. It is made up of international volunteers from all over Europe who visit the informal encampments and abandoned places where people in transit live daily. They bring food, clothes and share conversations and moments of exchange in an attempt to provide brief, temporary relief to the exhausting waits that those stranded here endure. The local population seems to live peacefully with the situation at hand – or at least with a general indifference to it – and indeed there are forms of solidarity that have been established by civil society over the years. Despite this, however, there is a significant refusal by locals to live in the areas surrounding the port.1

Furthermore, there have not been any institutional reception services in Patras for years, with the exception of a centre for unaccompanied foreign minors run by IOM (International Organisation for Migration) that accommodates fewer than 20 people. The Greek authorities’ decision not to have accommodation facilities seems to be a strategic choice – an attempt to discourage any kind of stay in the city and prevent migrants from trying to cross the sea to reach Italian shores. The consequences of this decision are clearly visible in the areas near the port where for years, hundreds of people have been camping and living in old, abandoned and dilapidated factories. The principle sites are the former E.G. Ladopoulos paper mill, the AVEX timber factory and the disused Peiraiki Patraiki textile industrial complex.2

They were among the most important production and manufacturing plants established in Greece and the Balkans during the 20th century. Ladopoulos, founded in 1928, went bankrupt in 1991, leaving more than 1,200 people unemployed, while the Peiraiki Patraiki factory, one of the most important textiles manufactures in Greece in the 1920s and 1930s, was forced to close in 1992 also due to numerous strikes and protests by workers. The area where these complexes can be found is extremely large and occupies a large portion of the Patras port area (Peiraiki Patraiki alone covers 194,524,74 square metres), demonstrating the important industrial role they once played.3

Their state of abandonment and decay, however, clearly reveals the consequences of the economic crises and processes of deindustrialisation, but above all highlights the ongoing deep employment crisis that has affected Greece and the Patras area, in particular, for decades.4 In recent years, these places have seen several redevelopment projects and attempts to rehabilitate the area by the Municipality of Patras, yet apparently without ever taking into consideration the constant presence of hundreds (and sometimes thousands) of people who have passed through, inhabited and occupied these spaces for years.

From what we could call squats, everyday dozens of boys and men between the ages of 15 and 50 climb over the walls and fences of the port and attempt “the game”. Some are trying it for the first time, others are on their twentieth or thirtieth attempt. “The game” is what is also called here – as in other places along the Balkan routes – the attempt to cross the border, to reach a Europe that everyone considers more “real”, since it is perceived as a place of greater opportunities and resources.

Doing so, however, is not at all easy. As many of the people in transit in these places recount in detail, to succeed you have to cling on, hide, squeeze into the blind spaces of the numerous trucks that embark in the direction of Bari, Ancona and Venice, with the hope that the police do not find you. “It’s difficult, you know… you have to be very quick, to hide carefully, not to get caught. If you manage to get to Italy, you win, but if the police find you, arrest you and send you back, you lose. The bitter irony behind the use of this term almost serves to exorcise the dangerousness and extreme uncertainty that characterises the lives and fates of these people.

Along the Balkan routes, in Greece as in Bosnia-Herzegovina or Serbia, “the game” is to all intents and purposes a spatial tactic – a strategy for regaining the possibility of movement and reacting to the attempts at disciplining them put in place by national and supranational powers. It is the only effective way to be able to cross the increasingly militarised and controlled borders and continue on one’s way.

Depending on the time of year, in the vast area of the Patras factories, around 200 to 300 people live and there is a constant flux of comings and goings. They are mainly from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran, all men, many of them minors. Most of them have been registered as asylum seekers in Greece for years and are waiting to be interviewed or to proceed with their appeals after having been denied. The stalemate and forced immobility imposed by the endless asylum procedures with their increasingly ineffective and inadequate bureaucracy, are what lead them to try “the illegal way” – to seek an escape route, to try to get a little closer to their goal and the beginning of their aspired life.

There are also those, however, who have managed to escape the bureaucratic meshwork and registration controls after crossing the Greek-Turkish border or have had their applications for international protection rejected (the so-called second rejection) and therefore find themselves on Greek territory illegally. These people inhabit a condition of extreme precariousness and invisibility, burdened by constant fear and uncertainty around the possibility of being deported or incarcerated for indefinite periods in the “pre-return” detention centres in the territory.

The factories where these migrants sleep, eat, pray, wait and prepare for “the game” are cramped, marginalised and marginalising places: they represent a non-space, a limbo in which time is rarefied, suspended. Here, the days seem all the same, they are punctuated by attempts to cross the border in trucks and by the moments in which one waits and recovers one’s strength in preparation for the next game, hoping for better luck. “If you are lucky you go and then, inshallah, you arrive in Italy. If no lucky, you just try another day”.

Despite the constant illegal rejections, enforced by both the Greek and Italian border police, denounced by numerous organisations, Patras is considered by many to be a difficult and exhausting passage. Yet it is also more porous and permeable – more viable than other borders along the Balkan routes. For many, attempting “the game” from here is one of the “easiest” ways to reach Italy. Albeit certainly one of the most dangerous.5

While some do succeed in crossing, many others remain stuck and trapped in this place. The immobility that surrounds their fate and their very will to move, to continue and to reach their destination, is often all-consuming, overwhelming and is compounded by the uncertainty and precariousness related to their legal status and the high possibility of being deported. As some of the volunteers and activists present tell us, apart from trying “the game” there is nothing else to do: “During the day, they just sit down and look at the port thinking how to do the game the next day in a better way. Hoping to be in Italy and to continue the trip soon.” The holding spaces that are created can weigh like boulders, blocking and disrupting migratory trajectories and routes: they are to all intents and purposes forms of control – devices for managing and disciplining otherwise ungovernable movements.

Rarely those who visit Patras are aware of what goes on within the skeletons of those abandoned buildings around the port or in the ferry embarkation areas. The reality of this city is not often told and is far from the limelight of the “border show” that characterises other situations of transit and passage of migrants. Here, bodies, experiences and paths are continually invisible, blocked, controlled, relegated to the margins, far from the gaze of visitors, locals and seasonal tourists passing through the city.6 Nevertheless, this place is extremely emblematic for the dynamics it creates and the trajectories that pass through it, certainly not unlike more well-known and mediatised places such as Ventimiglia, Calais or Bihać.

Many of the people who live in the factories of Patras and attempt to succeed in the game from this border, and who have previously tried to pass through Albania, Kosovo or Macedonia, have been rejected, deported, refused and now seek other ways, other routes, to obtain their goals. A dense web of paths and trajectories continues to develop, reproduce and change in the Balkan territories, from Greece to Croatia, Slovenia and Hungary, revealing the effects of a form of government over the mobility of people that also acts “through mobility”.7 It restrains and contains bodies, hijacks movement, curbs it, multiplies durations and forces the trapped subjects into a sort of perpetual motion.

Footnotes & references

[1] Zisimopoulou, K. Zisimopoulou, K.; Fragkiadakis, A. (2016) “The industrial buildings of Patras in the New Port Akti Dymaion area”, Patras Industrial Landscape, 2016

[2] Mogiani, M. (2021) “Borderless imaginaries, divergent mobilities: Migrants’ reappropriation of urban and logistical spaces in Patras”, antiAtlas #4

[3] Zisimopoulou, K.; Fragkiadakis, A. (2016) “The industrial buildings of Patras in the New Port Akti Dymaion area”, Patras Industrial Landscape, 2016

[4] A. Gianotti, “Senza lavoro da più di un anno, in Grecia anche uno ogni cinque“, Il Sole 24 Ore, 13 Jan 2020.

[5] The Border Violence Monitoring Network has long denounced the rejections that also take place on this border and so has the Association for Legal Studies on Immigration, ASGI

[6] Nicholas De Genova (2013) “Spectacles of migrant ‘illegality’: the scene of exclusion, the obscene of inclusion”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Volume 36, 2013 – Issue 7.

[7] Martina Tazzioli (2018) “Containment through mobility: migrants’ spatial disobediences and the reshaping of control through the hotspot system”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Volume 44, 2018 – Issue 16.

Images:

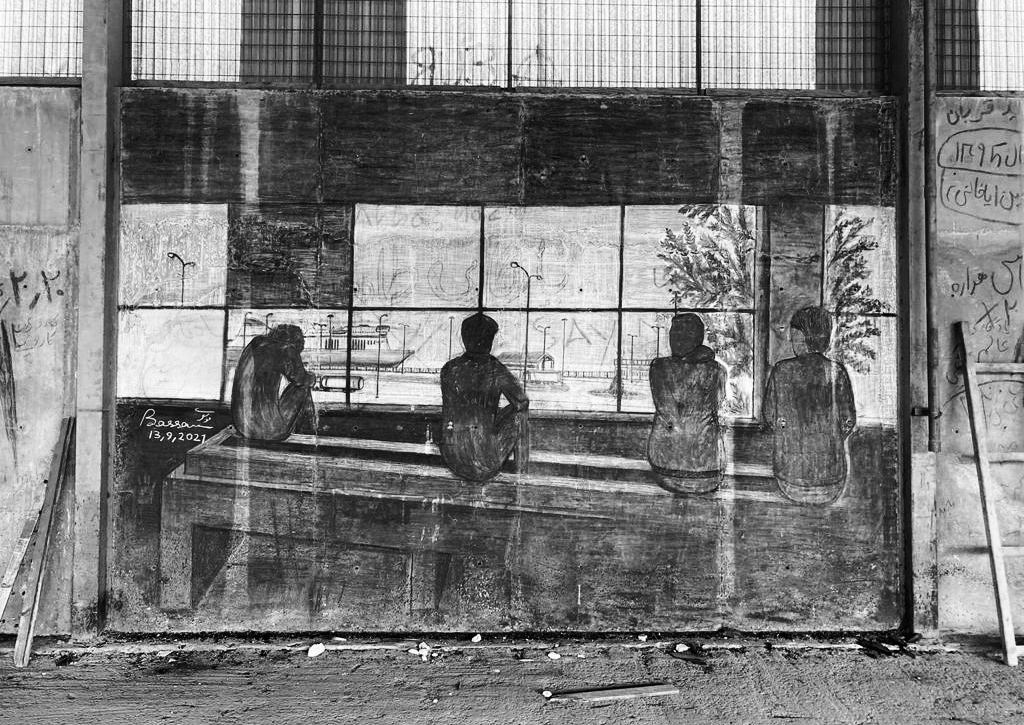

1) Top image: murales by Bassam Mousabi on a wall of the “wood factory” in Patras. Photo: Chiara Martini

2) The so-called “big factory” in Patras. Photo courtesy: No Name Kitchen

3) Port of Patras. Photo courtesy: No Name Kitchen

4) Port of Patras. Photo courtesy: No Name Kitchen

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »