Singing to Mama

Every February in Southern Italy, the LGBTQ+ community gathers for a religious event at the Sanctuary of Montevergine in Mercogliano, a small village nestled in the hills of Irpinia. The group collectively enters trance-like states which celebrate “Mama”, a local medieval black Madonna who is believed to protect the marginalised. Illustrated by film photographs by Gianluca Tesauro, this contribution recounts author Maria Betteghella’s active participation in those intense hours of the festival, where adoration, prayer, chants and traditional dance compose the ceremonial encounter with the holy image.

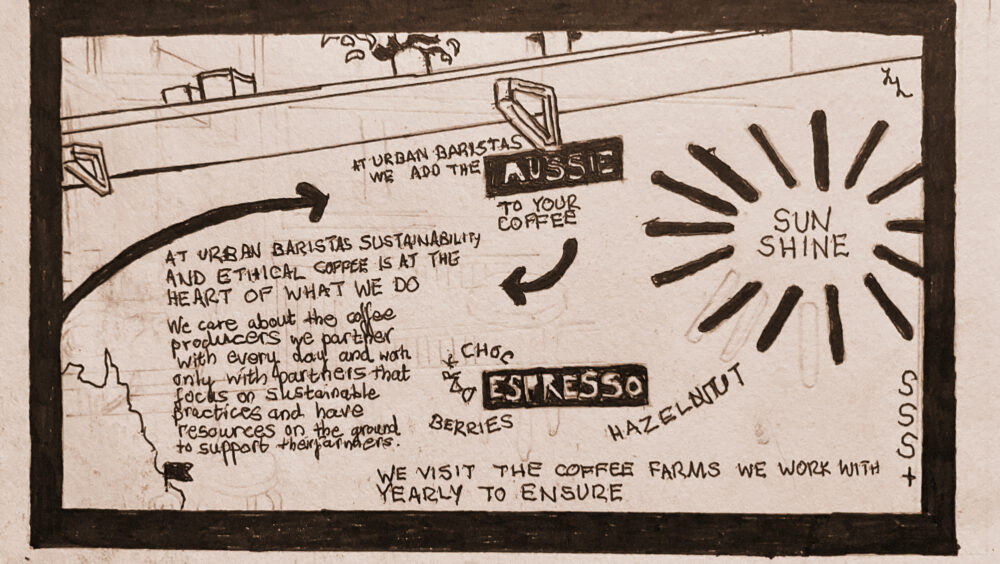

God speaks to each of us as he makes us, Rilke wrote, and while I was running short of answers I stumbled upon the unusual festivity of Mamma Schiavona (literally Mother Slave). Officially known as Madonna di Montevergine, the festivity belongs to a Marian cycle called The Seven Sisters, a catholic sequence of adoration that takes place between February and May in some of Campania’s most untravelled corners.

It’s the second of February, Candlemas day, and today Catholicism celebrates the presentation of Jesus at the temple, 40 days after his birth. I wake up at 6 a.m., put on my warmest clothes and start driving along a desert motorway. The Sanctuary of Montevergine stands on a 1,270m-high peak, towering over Mercogliano, a small village located in the Irpinia mountain region. A couple of hours from now, hundreds of pilgrims will flock to the village to celebrate the spring’s arrival and pay homage to the Virgin.

This tradition, however, is tolerated by religious authorities with reluctance. While not the only festivity with a burlesque drive, Montevergine is particularly disruptive, as its Madonna is believed to be the LGBTQ+ community protector.

The legend goes back to the 13th century, when Mamma Schiavona performed a miracle by saving a couple of homosexual lovers who had been banished from the city and imprisoned behind ice slabs against a tree. The miraculous liberation, by which a ray of light melted the ice, turned the Madonna into an icon of protection: to this day, those who experience a life of marginalisation gather at Montevergine on the second of February, in order to renew a sense of strength, community and hope.

The monastery was consecrated in 1124 near the ruins of a temple of Cybele, however the basilica was built only recently, in 1961. It is here, in the chapel, that a 13th century Byzantine icon of a black Madonna is displayed; it is here in front of this image where the most heartfelt moments of this cult gathering happen.

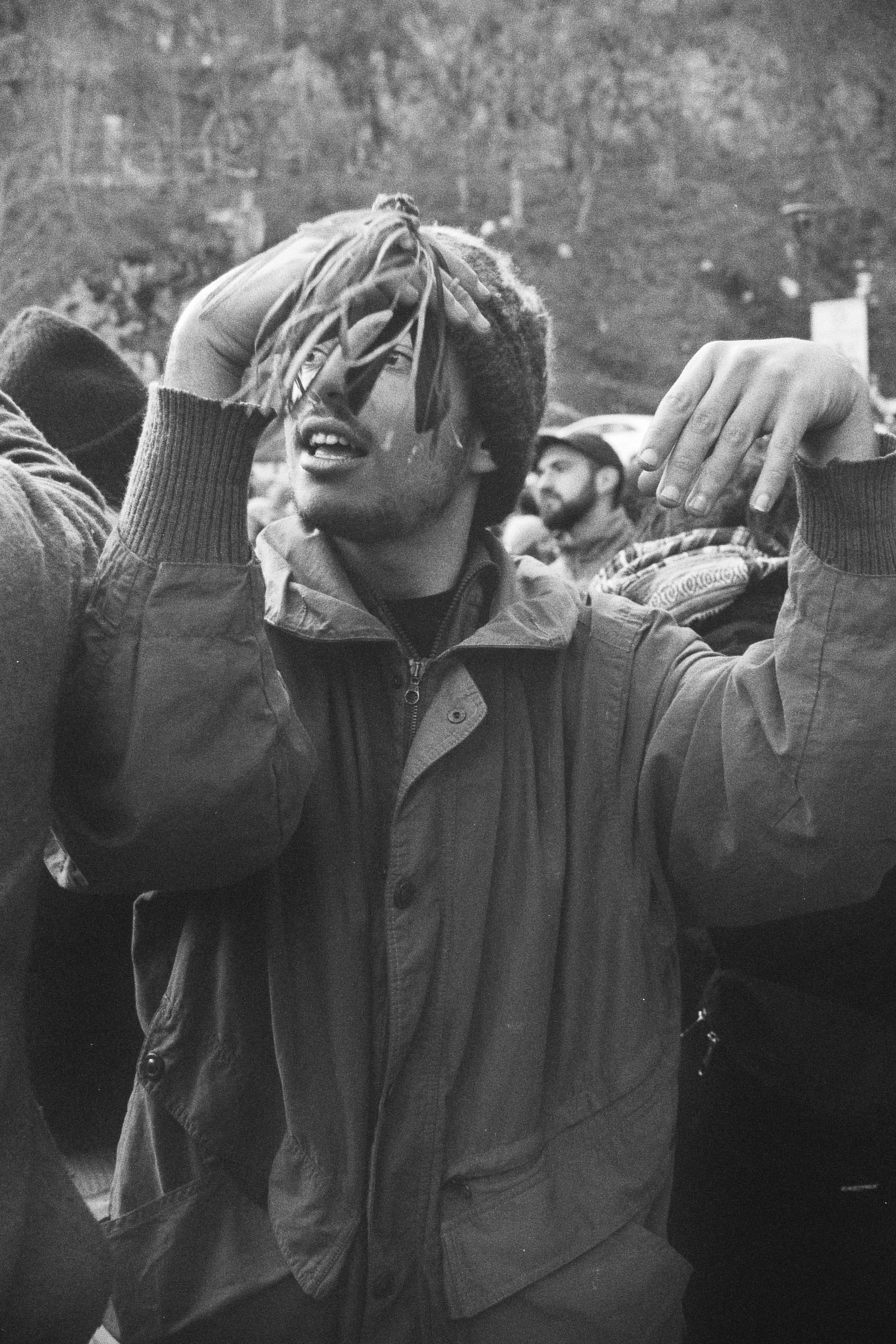

After parking the car, I line up at the funicular, but it’s early and there are only a few other people around. But when upon reaching the top of the mountain after a steep ride, I find a completely different scene. Frame drummers, accordionists and dancers are already gathered in circles to play the tammurriata, also called ‘o ballo e ‘o canto ‘ncopp ‘o tammurro, literally the dance and the frame drum chant.

Buses line up on the way to the monastery, but I also spot a few trekkers who’ve climbed the mountain themselves. Italian grandmothers go to mass while city boys fight the cold with red wine. Every now and then, I admire the elegant catwalk of the femminielli, a Neapolitan word literally translating in “little man-woman”. Beautiful, sensual creatures with an innate sense of beauty who defend their ambiguous identity with unrelenting pride.

The tamurriata is the most identifiable folkloric element of the Seven Virgins’ cycle of adoration, revealing Campania’s peasant background. The dance used to be a courting ritual, which is why it’s performed in couples. Man and woman maintain a strong eye contact over an insisting frame drum rhythm, often accompanied by an accordion. Although the dancers hardly touch each other, there’s a strong sensuality throughout the performance, often relayed by the songs’ lyrics.

E vota, vo’, someone screams – turn around. This is an invitation to spin, a specific moment of the tammurriata called votata. Dancers obey, grabbing onto each other in a spiral of legs and arms. This is the only time men and women have physical contact. I observe the couples while they look at each other, and it’s hard to decide if this dance symbolises attraction or combat. Most likely it embodies both. The tammuriata’s most inspired moment is the fronna, the opening chant that pleads for the Virgin’s mercy, a special way of connecting with the divine and propitiate the gods.

I leave the circles behind and reach the church entrance. I look up at the white stone staircase I’m about to climb and end up sitting for a minute before continuing the ascent. It’s eleven in the morning and all around I see people sipping red wine.

Today, Montevergine transforms into everybody’s home, providing a strong sense of community to pilgrims of different kinds. It’s a comfort we’ve forgotten in Western modern societies: the reassuring certainty that we can rely on our peers. A relaxing yet unknown truth: we are one.

I ask a man standing next to me for a plastic glass and he offers me chestnuts on the side. Two buses have just arrived from Naples and there’s a huge crowd of travellers and musicians gathering in the sanctuary’s courtyard. When I stand up, a long queue precedes me on the stairs that lead to the chapel. I have no choice but to join the line. I finally arrive in the crypt where silence is tangible.

I’m preparing to attend the most profound moment of the cult gathering. Soon, groups of prayers will make offerings to Mama in front of her icon. The ritual is changing year after year and media presence is a measure of the event’s popularity.

I’ve been waiting in the chapel for almost an hour, there’s no way out now. The crypt is packed with people. Above the crowd, the black, 4-metre tall Madonna stares at us from a golden, byzantine background that gives a distant texture to the Virgin’s gaze, as if it were reaching us from another world. Dressed in elegant, imperial clothes, she sits on a red throne and holds her baby with a gentle yet deadly-still hand. As I look at her in the silence of the crypt, I let my eyes choose what to see. I receive the images of a Turkish queen paired by that of an Egyptian goddess.

Nigra et formosa es, amica mea warns the effigy, paraphrasing the Song of Solomon. The black Virgin cult is rooted in Medieval culture, a time of unequaled spirituality, syncretism and creativity. I take a last look at the icon: her eyes quench my thirst, connecting me with the original source of life, the archetypical mother that brought us into the world, allowing the unfolding of our rambling humanity generation after generation.

A woman starts singing. She is surrounded by a group of men holding their drums in silence. The walk moves slowly and the group proceeds as a whole. The singer looks up at the Madonna and directs her prayers to her. I came from afar – she sings – and while I hear her divine voice, I realise that we all do. We all come from a space of safety and peace; our lives all start as an act of being thrown into a world of chaos and uncertainty.

I close my eyes and try to remember what it was like to be in my mother’s womb, the black mama observing me from above the altar. Suddenly, voices and sounds fade away, it’s just me and her. All I hear is the ancestral beat of a drum – bum, bum – it must be my heart, or Mama’s. Or both. Tears of joy fill my eyes, I ask for my personal miracle. I’m touched by the ritual and welcome the feeling of protection that only a mother provides. The divine power of ultimate love. A beating heart we hear for the very first time.

Bum….bum….bum…

Recent articles

Overlooking the Sicilian capital, Pizzo Sella is a natural promontory also home to hundreds of unfinished constructions – the result of a wave of illegal urban sprawl started in the late 1970s. Artist Erik Smith freely explores the enduring presence of these concrete ghosts, engaging with the fragments – materials… Read more »

Heliograph, Calotype, Talbotype, Daguerreotype: these are some of the early names that circulated prior to the word “photograph” during the early, experimental stages of its invention. This fascinating historical text from the mid-1800s lays out the early development of photography from a point in time when the technology had advanced,… Read more »

Between the areas of Spitalfields and Aldgate in east London, where Middlesex and Wentworth Streets converge to form Petticoat Lane, lies a stretch of market stalls selling clothes, street food and everyday goods. This very space became the setting for a short workshop on place-writing, held in October 2023 by… Read more »