Passing the past: a postscript

2015 marked the island city-state Singapore’s golden jubilee. Amongst the festivities and events celebrating the country’s independence was public coverage of the Dakota estate, one of the oldest public housing developments in Singapore. With its impending demolition to make way for redevelopment, the area was featured in numerous arts, culture, and heritage projects, propelling the conversation regarding nostalgia and redevelopment. That same year, artist and writer Joey Chin also created text-based art in Dakota as part of the art project Objects in the Mirror are Closer than They Appear. 5 years on, with the residents having vacated their flats and the area boarded up, she reflects on the brouhaha surrounding the housing estate.

Though it may not be widely known, around 80% of Singaporeans live in public housing apartment blocks. The blocks are commonly known as HDBs after the statutory “Housing Development Board” responsible for public housing in Singapore under the Ministry of National Development.1

Established in 1958, HDB was preceded by the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT). SIT was a governmental organisation, set up by the British colonial government in 1927 to provide affordable public housing as a solution to the overcrowding, sanitation, and safety issues that affected shophouses, villages, and squatter settlements.

As one of SIT’s projects in 1958, the Dakota Crescent estate and its residents received much attention in 2015. During the country’s 50th year as an independent nation, the ageing residential area became swept up in a narrative of nostalgia and romanticism of those ‘good ol’ days’, or the ‘kampong spirit’.2 Kampong – a term used in Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia – means ‘village’ in Malay. The kampong spirit refers to a sentiment of trust, servitude and camaraderie amongst villagers; sometimes extending, for instance, to residents not locking their doors or gates for their children and neighbour-playmates to run through.

When the estate’s redevelopment was announced for 2016, it suddenly became a focal point for creative individuals and organisations interested in vox pops, community dialogue, and engagement. The estate’s elder care centre, its iconic playground, and some residents became a cast of icons and characters: their faces, hopes, losses, and talents documented in heritage, community, writing, and media projects.

As an artist who explores communications and territoriality, the estate became a natural source of interest. So, I embarked upon a site-specific text-based art project Objects in the Mirror are Closer than They Appear in 2015. The project sought to look outside of the largely (popular) culture and heritage events surrounding the estate.

At this point of writing, Dakota has been emptied, boarded and is out-of-bounds to the public, but little demolition has actually taken place. Sneaking into the estate recently, I reflect on the re-presentations of the estates then and now with images taken in 2020, as a visual postscript 5 years on.

This sign serves as a warning and reminder for authorised personnel to contact their SMO (Safe Management Officer) before accessing the blocks. Apart from a workplace safety compliance in a construction site, especially one marked for demolition, this is also likely a COVID-19 social distancing measure where only a fixed number of staff are allowed on-site at any time.

Out of haste or carelessness, the project title is missing, creating an erroneous and humorous caption of Enter Project name here. There are multiple activities happening simultaneously, in the sign’s attempt, and somewhat, failure to assert its message completely.

Like the brouhaha surrounding Dakota’s estate, directed through the rear view mirror of memory and identity-building via nostalgia, the result was sometimes lacking in authenticity. The staging of presence and impending absence, including my own project with Objects, can only be seen when unseen, revealed through the passage of time, much like the project name not being entered.

As a nonverbal means of how people communicate possession and belonging to a physical space, territoriality is evident in this ground floor unit. Through personalisation and signs of the interests and beliefs of its occupants, this brightly painted ground floor unit, with its pale pink balustrade, stood out amongst other flats in the estate. A faded sticker of Winnie the Pooh and the animated comedy character SpongeBob SquarePants adorn the plastic bi-fold door to the side.

Territoriality also extends to the social idea of a collective nostalgia as a nation, and the Dakota estate in a way, resonated with a shared identity, history, and its future. The days of yore of what the country was; like the flat’s last occupants taking pride in marking something unique and personal. What the country can be; like the previous owner’s aspirations moving out, and forward. Two small Islamic scriptures are still attached to the left panel of the door. It is as though as the concept of belief, similar to memory, will continue to follow even when out of sight.

With a camera and unrestricted access to the estate’s grounds and common areas while working on Objects in 2015, I was able to direct my gaze towards an artistic interrogation and mission. Like the technique of projection-mapping, where moving images and lights wrap around a space, the Dakota estate and its residents were present, and positioned as a presence which could be touched, observed, and mapped.

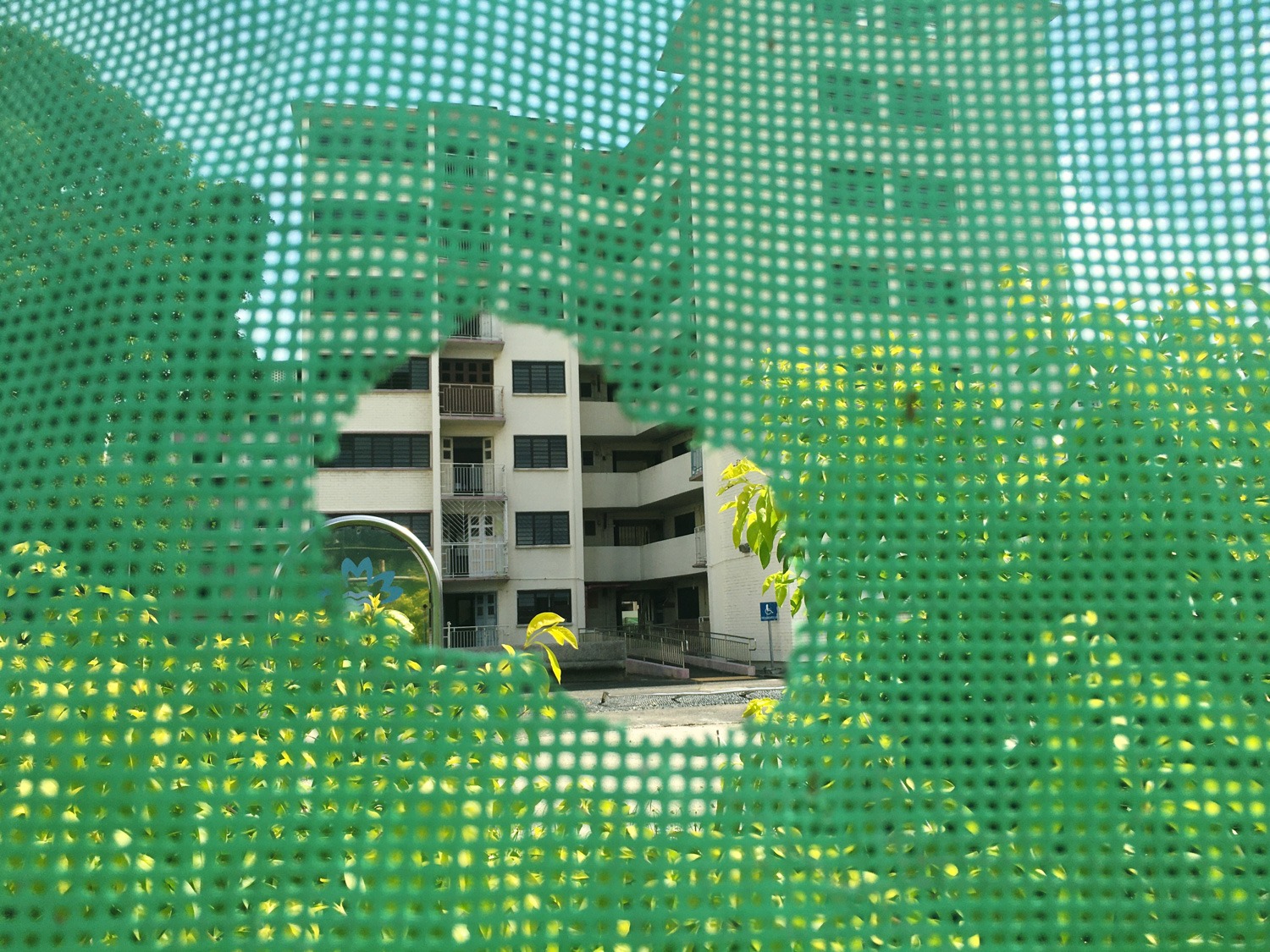

Today, green mesh panels wrap round some parts of the estate. Approximately 2m in height, they conceal views of the deserted flats, though slits and holes possibly made by vandals make these net-like barriers less successful. The higher panel modular hoardings are the more solid barricades to be erected. Whereas the estates were previously looked upon, they now do the looking.

The obstructed views are a counter-gaze of Dakota. Once the subject now turned gazer, the estate is reclaiming itself by keeping out the public eye. The destabilisation and reinvention of the same place through a new context returns to Dakota its original privilege of privacy, even if the residents are gone.

As an old estate like other HDBs, the design for airing laundry consisted of steel brackets attached to the ends of the ceiling. This was for units on the ground floor. For levels above the ground floor, pipe sockets were designed for laundry poles to be inserted into. Personal artefacts in view to others simply meant that the airing of laundry was visible to all and sundry. Even if ignored or noticed unintentionally, the occupants, though out of sight, are somewhat seen through their undergarments, underwear, uniforms, and clothing hanging in the open.

At times after having watched documentaries and read articles and projects featuring residents and their personal stories of loneliness, aging, disability, death, and financial issues, I often wondered about the vulnerability of people and the ethics of cultural and heritage projects. In the airing of the metaphorical linen and laundry, whose stories are we telling? Is it the people’s, the filmmaker’s, the artist’s, the funding bodies’? With these sockets and brackets emptied of laundry poles, where are these stories now? Do we still pursue them, and to what end?

To quote Robert Hass’ opening lines of Meditation at Lagunitas:

“All the new thinking is about loss

In this it resembles all the old thinking

The idea, for example, that each particular erases

the luminous clarity of a general idea.”

Sentimentality and nostalgia for Dakota, ultimately comes from a place of loss: impending or already lost. The art, culture, and heritage projects, and even mine, is a negotiation of defining ourselves from point A arriving at point B, and the ephemerality between these two points.

The current re-presentation of Dakota in its isolation, when left untouched by heritage hunters, has broken down the previous storylines of others, taking on a new materiality and narrative by itself. At present, and until redevelopment is complete, Dakota is free of any tropes or icons through which it can be defined without consent. Dakota, in reaching its end, has only just begun.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »