Of foxes and men

Sharing the fabric of our cities with wild animals is the norm. As long as they do not encroach upon the boundaries of the domestic wall, the space in which we live is also that of birds, mice, insects and other species. In London, urban foxes are the most iconic yet fragile manifestation of this inevitable coexistence. Filmmaker and researcher Alžběta Kovandová shares her thoughts and personal experience of these fleeting encounters.

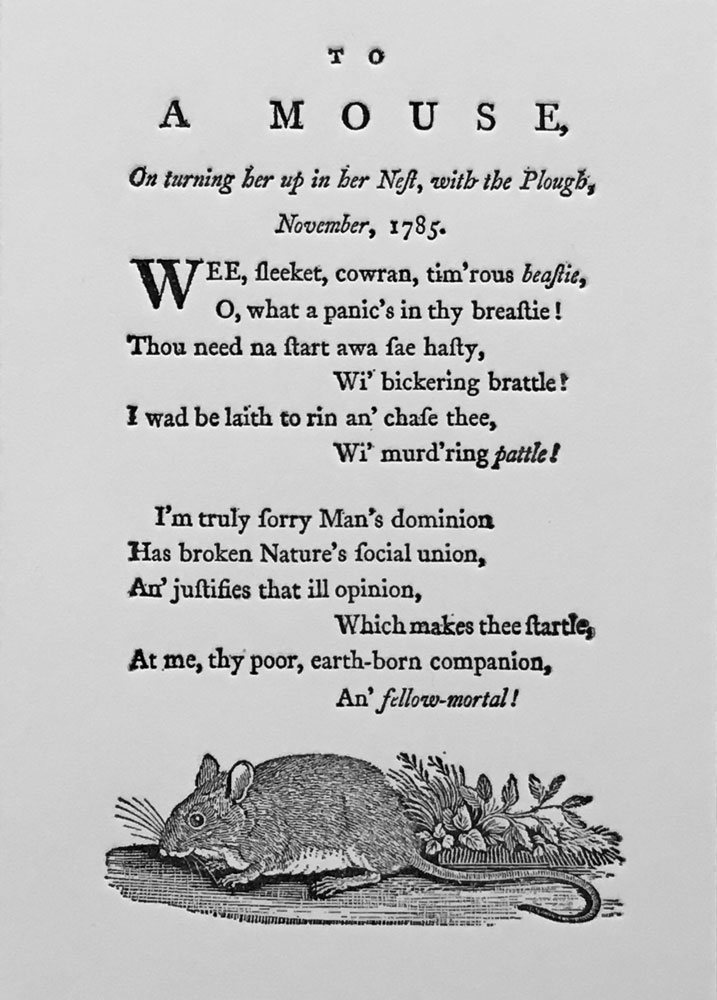

When John Steinbeck finished his famous 1937 book, he decided to name it Of mice and men to pay tribute to Robert Burns’ 1785 poem To a Mouse. In this poem, Burns apologises to a mouse for accidentally destroying its nest. Although Steinbeck’s book inspired the title of my article, the topic relates rather to Burns’ poem, part of which reads:

I’m truly sorry man’s dominion

Has broken Nature’s social union,

And justifies that ill opinion

Which makes you startle

At me, your poor, earth-born companion

And fellow mortal!

I doubt not, sometimes, that you may steal;

What then? Poor beast, you must live!

Burns truly regretted damaging the nest with his plough since it meant that the mouse would most likely die during the upcoming winter. Nowadays, the approach to animals living amongst us is rather different, at least for some of us. On Boxing day of December 2019, prominent lawyer Jolyon Maugham announced on his Twitter account that he had clubbed a fox to death with a baseball bat in his garden located in central London. He was hungover and wore his wife’s satin kimono. The fox was trapped in the protective netting around his henhouse. The RSPCA investigated the case and Maugham claimed on Twitter: ‘To be quite honest, although I don’t enjoy killing things, it does come with the territory if you’re a meat eater.’ But does it really come with the territory?

In the 1970s, London boroughs were responsible for their fox control, however, this law was abandoned in the 80s and now the rules about what one can do to remove a fox are fairly strict. It is prohibited to block or destroy a fox earth if it is occupied; to use gassing or poisoning or to place snares in urban areas or public spaces. It is however allowed to humanely kill a fox if it is in the trap or snare, or by using a suitable firearm and ammunition. Nonetheless, after you remove a fox from an area, their territory will, most likely, be claimed by another fox within a couple of days. Foxes hold their territories, which can span from 0.2 square kilometres in urban areas to 40 square kilometres in the hilly countryside. These territories are inhabited by fox family groups which, in cities, usually consist of one dog fox, a vixen and their 2-5 cubs. Foxes have been sighted in suburban areas since the 1930s and, based on the 2013 DEFRA (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) report, the fox population in Great Britain is around 258,000, fluctuating slightly from year to year, but relatively stable.1 Roughly 33,000 foxes live in urban areas, sharing the city with us, humans.

Maugham’s behaviour towards a fox prompted me to think about our own territories: to what extent do we defend these; how strongly do we consider a city as ours. London became mine only recently, after more than a year of living here. On the other hand, Prague will always be mine because that’s the place where I was born and have spent most of my life so far. I have never seen Prague as a stranger. I do not know what it means to see the city for the first time, to explore hidden places and to behave like a tourist. Because it is my territory which can only be rediscovered, never truly discovered again. The process of getting to know a place is irreversible, unless the place undergoes some significant changes.

After moving from Prague, I spent two years living in Liverpool and inhabited a new territory for the first time. During these two years, the city of Liverpool changed – but mainly in my eyes. When I first arrived, behind every corner was something to discover. I tried to choose a slightly different route to work every day; I never looked down at the pavement but stared at the buildings surrounding the narrow streets. The city was someone else’s and there was a need for thoughtful observation and exploration. I soon began to like what I found. Liverpool is frequently used for filming but rarely represents itself. Due to its architecture, good services and affordable cost of filming, Liverpool often substitutes New York or London. However, I liked Liverpool itself. With its friendly welcoming Scouse people, calm days and frenetic nights, endless football enthusiasm, declared ‘Total Eclipse of The Sun’ (a boycott of The Sun newspaper because of its reporting of the Hillsborough tragedy), contempt and reverence towards London, remnants of old industrial glory and misery in the course of Thatcherism. The air in Liverpool is saturated with sea salt and the cackle of seagulls dominates the soundscape.

My perception of the city then changed – after two years I looked down at the ground as every other person on the street and when I left, it felt like I was abandoning a dear childhood friend. My territory spanned across all the streets I walked, through every cafe and pub I visited. I never remembered the city of Liverpool only through the images of the two tiny flats I lived in, but rather, I perceived it as a whole.

When I moved to London, I had no idea there were foxes. I did not know that there were other city dwellers apart from us, humans. I’ve always claimed that foxes are my favourite animals, I’ve admired them, I’ve found them fascinating. Yet, it was not until I moved to London that I actually saw one in the ‘wild’.

One might argue that seeing a fox is the same as seeing a cat or a pigeon. Well, not for me. It was unexpected and somewhat surreal for me to meet an animal that I associate so much with wild nature in the streets of London. They are not very common in Prague; and in Liverpool where nature bursts through the city only very hesitantly, it is rather rare to encounter any animal passing through the streets. I, therefore, strongly associate foxes with London and these wild non-human city dwellers, with their amazing ability to find a home in the concrete jungle, have influenced my perception of the city.

Their presence brings a sense of wilderness to the fast-paced human-made environment, adding an element which we cannot fully control. The queen might own all the swans, but no one owns the foxes – the most common non-domestic urban carnivore. Foxes claim their territories, not respecting our own human borders and boundaries, demonstrating remarkable adaptability and inventiveness when finding their way to human abodes. As a 2019 study, published by the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology suggests, foxes were partly domesticated alongside dogs in the Bronze Age.2 Yet, whilst dogs became our beloved pets, foxes reclaimed their independence. At least partially, since urban foxes often rely on human waste and mainly scavenge, even though they do have the same ability to hunt as their cousins in the countryside.

The practical contribution of urban foxes lies in rodent control; 55% of their diet consists of natural prey and scavenged meat, 20% is insect and worms, 7% fruit and the remaining 18% is household leftovers. Londoners do not always like the foxes, claiming that they are too intrepid and can be dangerous to people and pets. However, if it weren’t for the food waste, foxes would never survive in big cities – humans themselves have created the perfect habitat for these animals.

I will never get to know London in the same way as I know Prague or Liverpool, simply due to its size, but also because there will always be that feeling of anticipation that an encounter with a fox might occur. This sense of chance and surprise waiting behind every corner, this pleasant vigilance which I never experienced before, accompanies me as I criss-cross the city of London. These fox encounters tend to be very fragile. Even though I have heard many stories about fearless foxes, ‘mine’ are always shy. We usually meet around midnight, in our street in West London. There is an old church behind which is a tiny garden belonging to an abandoned vicarage. In this no-man’s land, where nature dominates and the ivy tendrils overgrow the garbage, I believe foxes have their earth.

When coming home, I tend to take a detour around that church, hoping to see a fox. Sometimes it is just a tip of a tail disappearing behind a corner, sometimes I do not see any, sometimes we meet face to face and stare at each other for a couple of seconds, sometimes I quietly follow them until they, sooner or later, disappear into the darkness. Usually I meet only one or two. Once I saw six of them at the same time in front of that old vicarage. That was a lucky day. Other people seem to ignore them, which makes these situations even more unreal. As a filmmaker, I always feel the need to capture these encounters, but their speed, bashfulness and erratic movements make these foxes almost impossible to film. Yet, this is only my personal experience – in more residential suburban areas, human-fox interactions are more common and less fragile, as gardens and parks offer a suitable place to sleep in and build earths. When foxes sleep in parks, people don’t mind them. It is when they breach human territory and do not respect the boundaries.

As I live in a flat, I cannot imagine what it is like to have a fox dig in my garden, eat my leftovers or scare my hens. Yet, it has been more than a year now since Vlasta, our squirrel, started coming to our balcony. She drinks water from our plant pots, leaves residue of food everywhere and we did not have a chance to taste any of our balcony-grown tomatoes – she harvested all of them before us. However, since she does not come inside, I am willing to share my territory with her. She is a fellow Londoner. That is what I read, not long after coming to the capital and having felt that sense of belonging, so important for a newcomer: when you move to London, you immediately become a Londoner, anyone can find home in London, anyone can live in the Big Smoke. At least in theory, it should be noted. So, what about foxes (and other animals)? They were born here and cannot move ‘back’ because they have adapted too well and would not survive in nature. Why do we praise our territory to such an extent that we cannot appreciate the beauty of the wilderness in our streets and accept its vices?

Burns was right: ‘I doubt not, sometimes, that you may steal; What then? Poor beast, you must live!’

Footnotes & references

[1] DEFRA – Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. (2018). ‘Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)’. Retrieved: February 15, 2020 from https://www.mammal.org.uk/sites/default/files/DEFRA%20red%20fox%20research_1.pdf

[2] FECYT – Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology. (2019, February 21). ‘Foxes were domesticated by humans in the Bronze Age’. ScienceDaily. Retrieved: February 15, 2020 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/02/190221122922.htm

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »