Life Magazine, 1965

A dive into the period in which skateboarding was blooming: by flipping through the pages of a 1960s issue of Life Magazine, Flavio Pintarelli recounts the way in which the board broke into the city, inaugurating new embodied experiences of space.

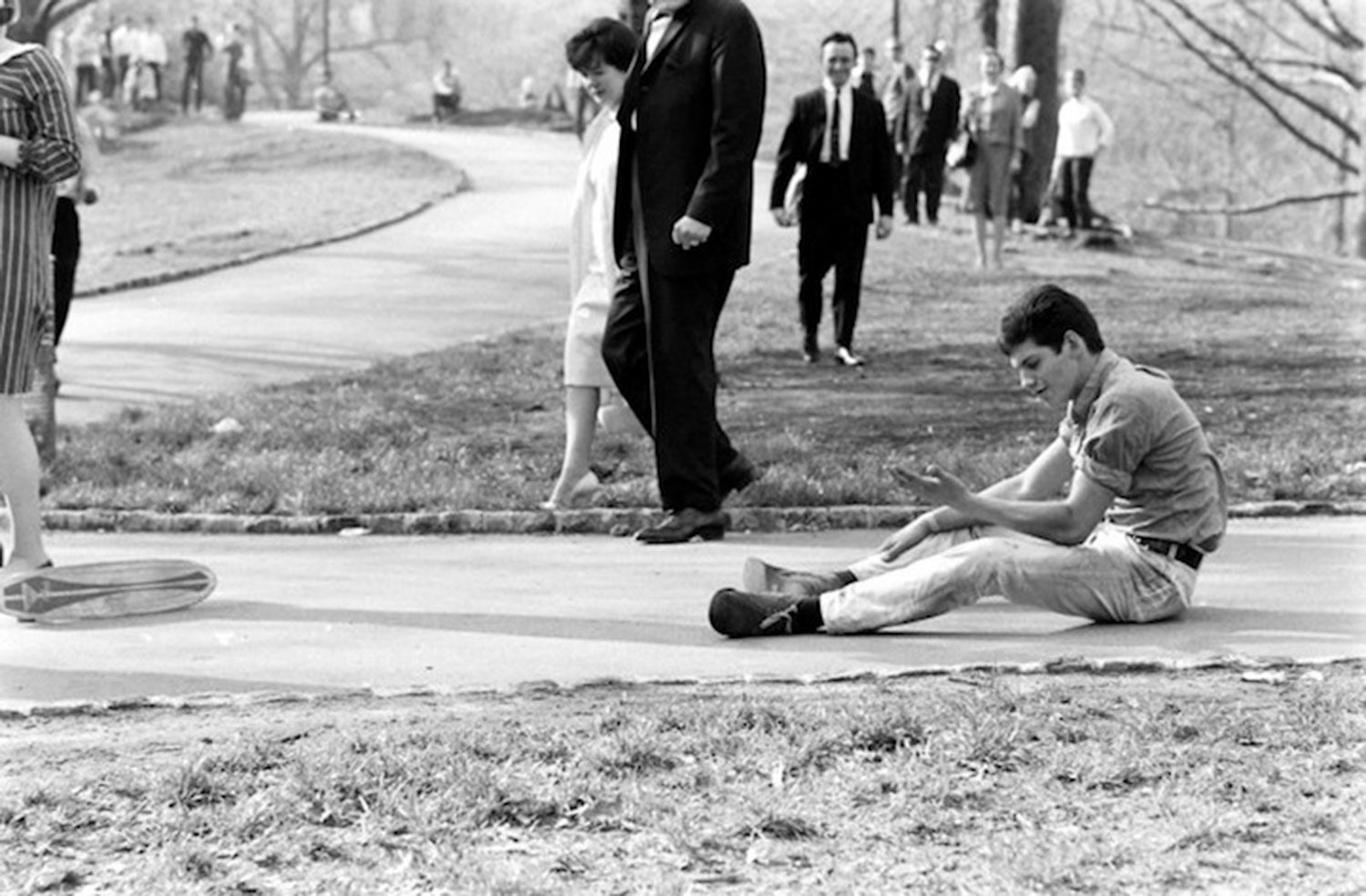

The boy in the photo has his shirt tucked into his trousers. The sleeves, short, are rolled to halfway up the bicep. He’s seated on the ground, in the middle of a pathway. On each side, beds of mowed grass, bordered by a low row of square bricks. He looks at his left hand. The right caressing his leg, just under the knee. Next to him a couple walks by. The head of a man, dressed in black, disappears over the top edge of the image, cut by the frame. The woman, in white, delicately places a foot on the grass. She seems to emerge from behind the silhouette of her partner. There, below, she notices something. I follow the gaze. Put into focus. In her eyes there is a flicker of uncertainty. What is that vaguely oval-shaped object resting on the path?

The light colour that dominates its surface, streaked by two dark bans, irregular, mixes against the leg of another woman – a striped dress, to the knee – who can just be seen in frame. I recognise that skateboard. Small, primitive. It’s from the pre-history of this sport. It’s a trace, a carbon isotope with which we can date this evidence. How many times have I made that same gesture? How many times have I contemplated the marks left by the contact with the concrete? The gravel mixed with blood and the shavings of skin, rising scattered around the scrape?

Meet Bill Eppridge

A Caravaggesque light illuminates the scene. It rains from the top of the frame, carving out shapes in the darkness of the night. The body of Robert F. Kennedy lies on the ground. Against the blackness of the suit, fused with the floor, the whiteness of his right hand, closed in a fist, and the left side of his illuminated face stand out. Leaning over him, his shocked gaze directed towards the car, the dishwasher Juan Romero places a hand on his shoulder.

On this evening, the boy, barely 17 years of age, does not know the lens of the photographer, Bill Eppridge, has just consigned him to history. Eppridge, on the other hand, is perfectly conscious of the weight of that which he is about to immortalise. In his mémoires, he will write that he had been preparing for ten years, for a moment like this.

It is 00:15 of the night, between the 5th and the 6th of June, 1968. Shiran Shiran has just shot dead senator Robert F. Kennedy with eight gunshots. He (will later say) says he did it in retaliation, since the senator had backed Israel during the Six-Day War. The rising star of JFK’s younger brother is snuffed out that evening, as he leaves the Ambassador Hotel’s ballroom in Los Angeles, where he had just celebrated his victory in the Democratic primaries of the state of California.

William E. Eppridge (1938-2013) is following that electoral campaign on behalf of the weekly Life Magazine. Born in Buenos Aires and raised in Virginia, Tennessee and Delaware, he is one of the most prominent photographers of the magazine, for which, a few years earlier in 1965, he signed a report documenting the explosion of a new trend on the streets of New York.

In those shots, Eppridge captures the joy and excitement of children and teenagers. Browsing through them, one can perceive all the nuances of a feeling that I could not describe in words other than: fun carefree, without worries. The series is called Skateboarding in New York.

The pages of the magazine rustle between my fingers. I appreciate the grain with my fingertips. A film of dust, the moisture that thickens the pages and some slight discolouration speak of a time from long ago. How many other hands must have held it, I wonder, before ending up in mine, that took it from this stall of antique trinkets, underneath the branches of the trees that line the most famous promenade of my city. I linger on another shot.

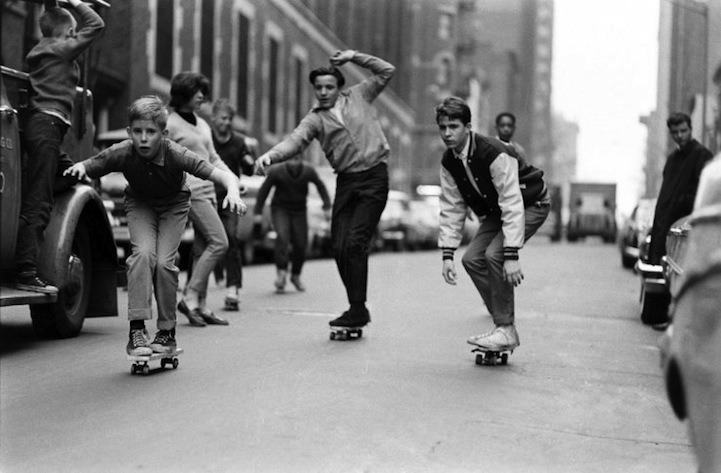

Three young boys in balance on the boards. Poses that oscillate between the bravado of the teenager in a college jacket on the right; the instability of his friend in the centre, who, whilst waving his arms, moves his hips in order to compensate for the imbalance; and the concentration of the youngest of the three. Leaning forward, arms open, bent at right angles, outstretched to grab the victory in what appears to be a fully-fledged race that arouses the excitement of a group of peers. A man, wrapped in a coat, hidden on the right between two cars, observes the scene. What sound was produced by those six pairs of polyurethane wheels on the pavement of that New York street which blurs into the background of the frame? We can interrogate the photo as much as we like, but that sensation is lost forever.

Cruising

The English verb, cruising, literally means ‘to cross’. In nautical terminology it indicates the act of ‘methodically tracing a certain sea area with one or more ships, to explore it’. Probably it is this form of movement – simultaneously methodical in its combing of a portion of space, and yet casual in the discoveries that could be made in it – that skateboarders thought they were referring to when they appropriated the word cruising to indicate their urban derives.

Skaters are explorers of the city. They comb its surface inch by inch, in search of signs that indicate a terrain suitable for being bent to the logic of their activity. In doing so, they sharpen their five sense and train them to recognise details that, to an untrained body, would escape or be completely insignificant.

The grain of the asphalt, the slipperiness of an edge, the arrangement of architectural elements or urban furniture run along like points on an ideal line that can be connected by the performance. All this is expressed in the skater’s perception as a visual, aural, olfactory, tactile and, why not, also a gustatory datum. Who has never experienced the taste of dust rising and falling when entering a long-abandoned space?

Their movement within the city is a journey of discovery, which brings them or in contact with spaces that are limits, residuals, negatives of all the elements that identify a city as the one-specific-city in the circuit of economic exchange through which it is enhanced or rewritten the most characteristic spaces of the city, bending them to its own specific uses. The skater lives in the slums and, at the same time, colonizes urban landmarks. If in the first case he exposes himself to risk, in the second he himself becomes risky (for power, for the grammatical order that regulates the city and establishes who can or cannot be part of it).

The constant, daily practice of this exploration develops a different sensitivity in skateboarders, for quality, of the city that lives, of the urban space that surrounds it, in which it is immersed. If it were not for the board, a prosthesis that mediates the relationship between body and space, this sensitivity would not hesitate.

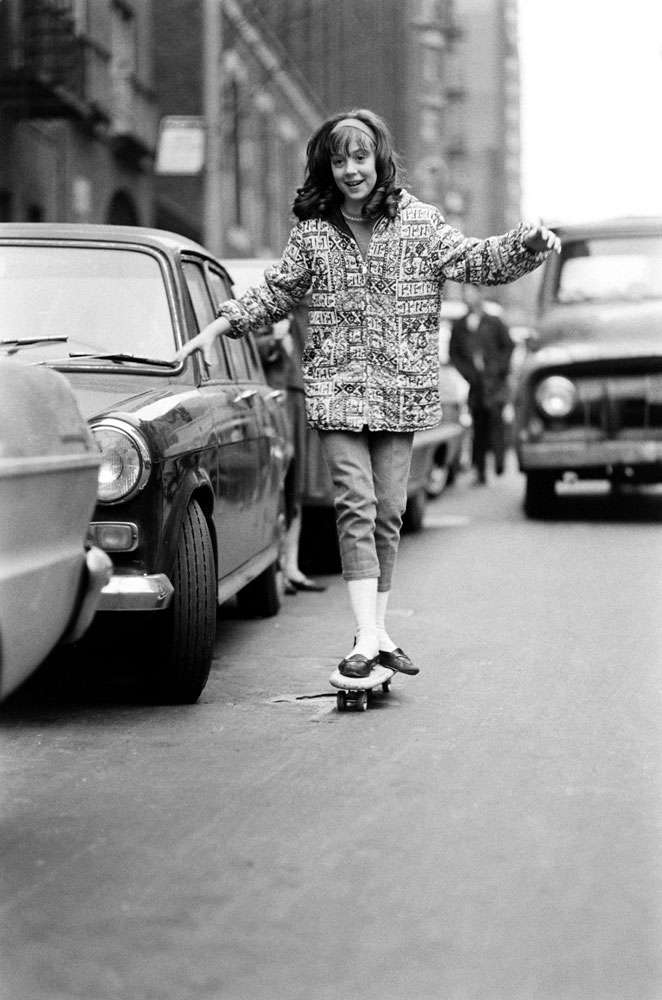

Something crosses the girl’s body. It rises from the bottom upwards, like a flicker, a current of electricity that is discharged into the air through its upper extremities. You can see it from her gaze, from the ecstatic quality that her expression transmits. I look at her and find a dazed note in that gaze lost in the void, in that smile stuck halfway between an eruption of joy and the uncertainty of success. All around, the light swaying of her hair, whose curls, perfectly formed, winks at me, amused by the black and white of the photograph.

Flat, shapeless shoes. Short trousers below the knee, long white socks. A jacket with geometric motifs. I imagine it’s colourful, flamboyant, the garment of this dryad who, drunk with a cocktail of new sensations, glides lightly among the parked cars. She has conquered the centre of the road. She seems to be savouring, for the first time, the taste of that challenge to the hierarchy that permits cars to reign over that strip of asphalt. But that’s not the centre of her experience. It is not in this rebellious gesture that the essence of that moment lies. The point lies in letting go. Surrendering to the flow, to the movement, correcting with light, calibrated yet uncertain gestures, the motion transmitted to the body by the board. There is a whole new world of equilibration and mechanics, that expands the perception of the senses. And there, in that instant in which the light imprints the film, I see it in its entirety, in all its liberating potential. A rustle of leaves interrupts me from reading. I discover my legs, and my feet, are swinging. So the memory of those gestures has not abandoned me? Something must have awakened it.

Expressive spaces

The skateboard is a medium. It puts into communication, the body with space and space with the body. It does this by acting as a prosthesis that modifies the body, amplifies and rewrites its sensations. It places ten to fifteen centimetres of height between you and the ground. Yet, it is in that displacement that there is also an intersection. The truck – the metal bridge to which the wheels are attached – allows the skater to roll. The skater’s motion is enriched by the twists and turns, he opens up, he breathes, he rejects, he avoids obstacles or connects them in a trajectory, that yes, is inevitably linked to progress, to progress – no turning back when standing on the board. But this progress is never inevitable, it is not destiny. It is chance, a chance in which we can transmit a direction, imprinting a mark of our will.

In Phenomenology of Perception, the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty speaks of the body as an ‘expressive space’, what is ‘the origin of the rest, expressive movement itself, that which causes them to being to exist as things, under our hands and eyes’.1 Our body functions as a unit of measurement of the space that surrounds it. The body does not exist, within space, as mere content within it. It is through the action of the body that space is shaped into its constituent elements. It is not the body that responds to the solicitations of space, rather, it is the latter that is shaped by the meanings that our body projects towards the external. To describe this mechanism in relation to skateboarding, the American architectural historian, Iain Borden, coined the concept of ‘body space’.2 An embodied space. Borden reinterprets skateboarding as an experience that transforms the body, the skateboard and architecture into a complex machine in which the three components cooperate in the creation of space.

In Borden’s thought, space is understood as a processual entity that is open and modifiable. When a skater faces a gap, such as the space that marks the edge of the pavement, they make a corporeal gesture that, through a technological construct (the board) combines two surfaces, which had, until that moment, been separate and gives them a new meaning. Even when a skater is engaged in a session (a series of sequential tricks whilst moving through space), their bodily gestures create bonds between distinct elements of space and they do so by developing their reading (perception) and their writing (performative gesture).

The capacity to read and write space, which is proper to skateboarding, is an integral part of the embodied experience. Borden writes: ‘In summary, skateboarding is a destructive-absorbent-reproductive process of the body and architecture; a performative act in which the body and the space are deconstructed, mixed and reconstructed in a new combination that is always different’.3 It is in this particular aspect of experience – in the capacity of perception to expose us to the panorama that surrounds us and at the same time to project ourselves into it – that we must search for the root of the difference between the skater’s gaze over space, compared to that of another.

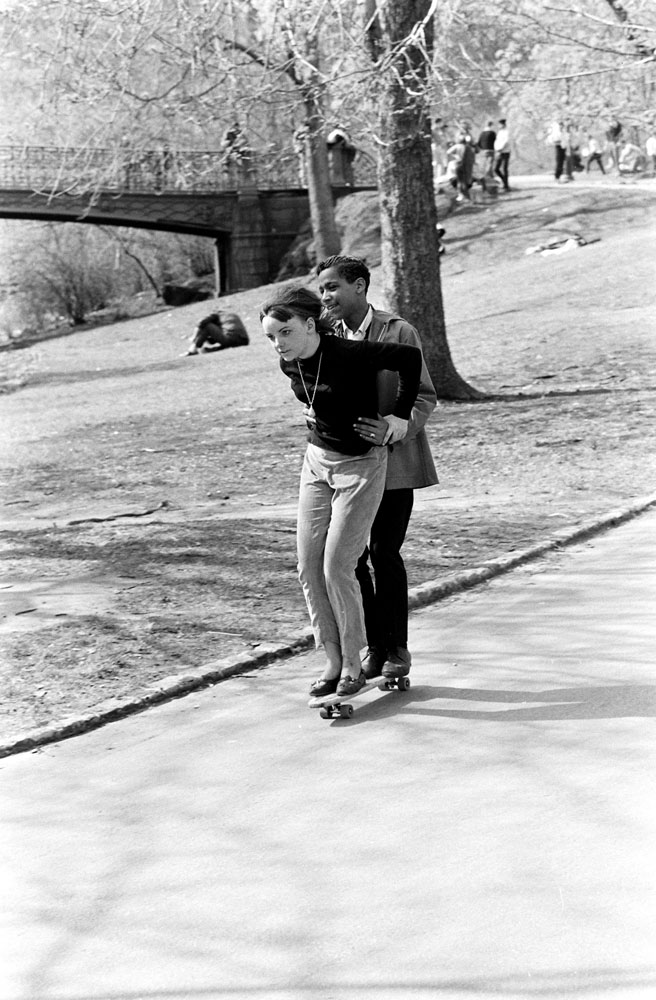

I see them descending a slight slope. Squeezed together, they slide down the path, riding a skateboard in two. She is wearing a fine black jumper. She flexes her knees slightly, her chest bent forward. She ploughs through and divides the air with a concentrated expression whilst grabbing the guy’s wrists behind her. The grip is firm, like a captain’s hands gripping the wheel. Even if the sea is calm, you should never relax. The girl leads the game. He merely indulges her. Peeking over her shoulder. A nervous smile is drawn on his lips. He places his hands on her waist. In that gesture there is no rapacity whatsoever, rather uncertainty and, I can’t tell, but perhaps an ounce of fear. Will we make it to the end? And when we are there, what will happen? I wonder if these are the thoughts that stir in the boy’s mind.

They pass by and disappear from view. A mischievous gust of wind turned the page. Will we make it to the end? And when we are there, what will happen? I remain hanging on these questions and, as I try to find the gesture again, I remember a thought. Are they not the same questions that define a love story?

Footnotes & references

[1] Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2002). Phenomenology of Perception. Tans. Colin Smith. London & New York NY: Routledge. p.169.

[2] Borden, Iain (2001). Skateboarding, Space and the City: Architecture and the Body. Oxford & New York NY: Berg.

[3] Ibid.

______

All images by Bill Eppridge, originally featured in Life Magazine, May 14, 1965

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »