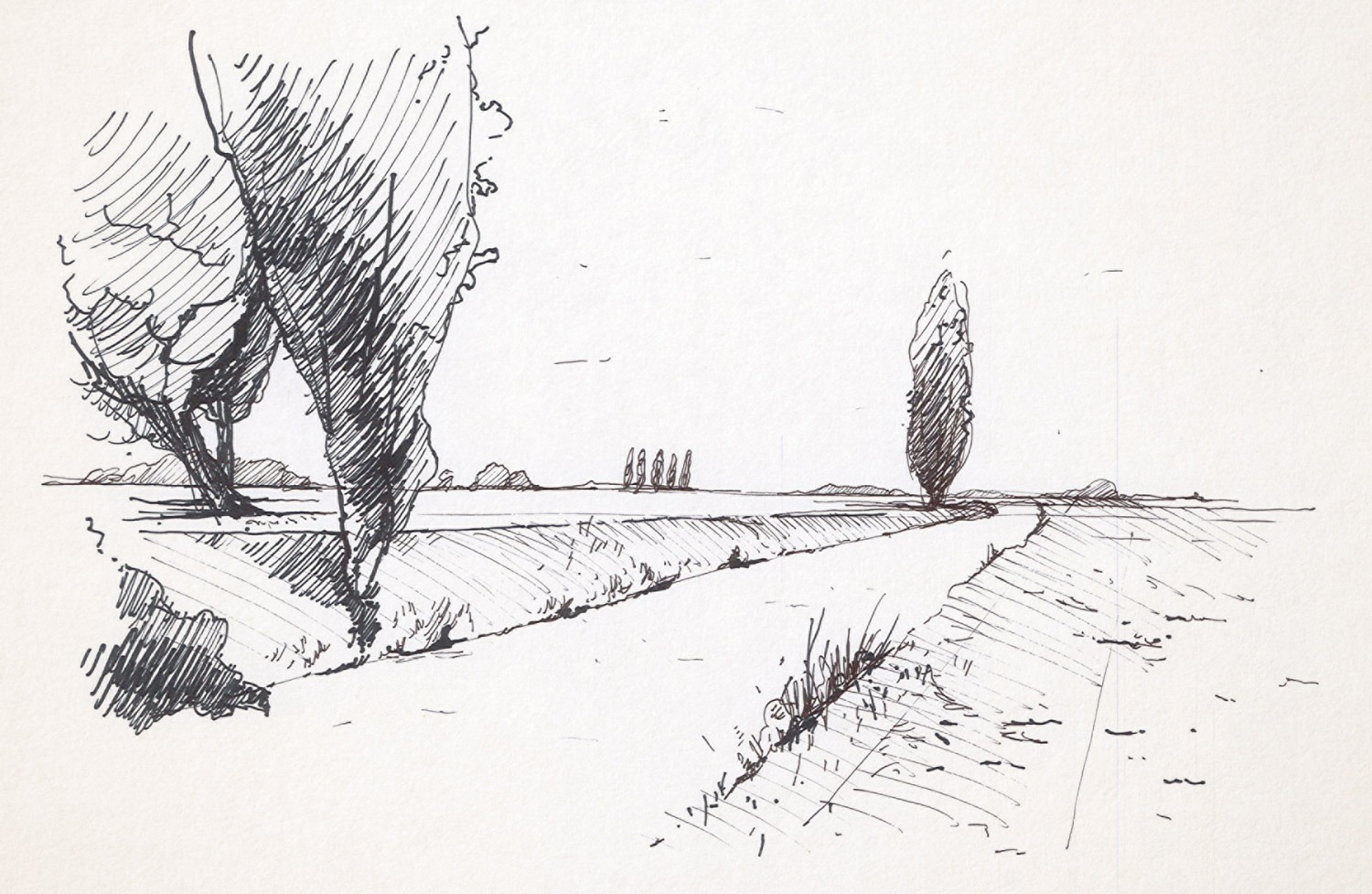

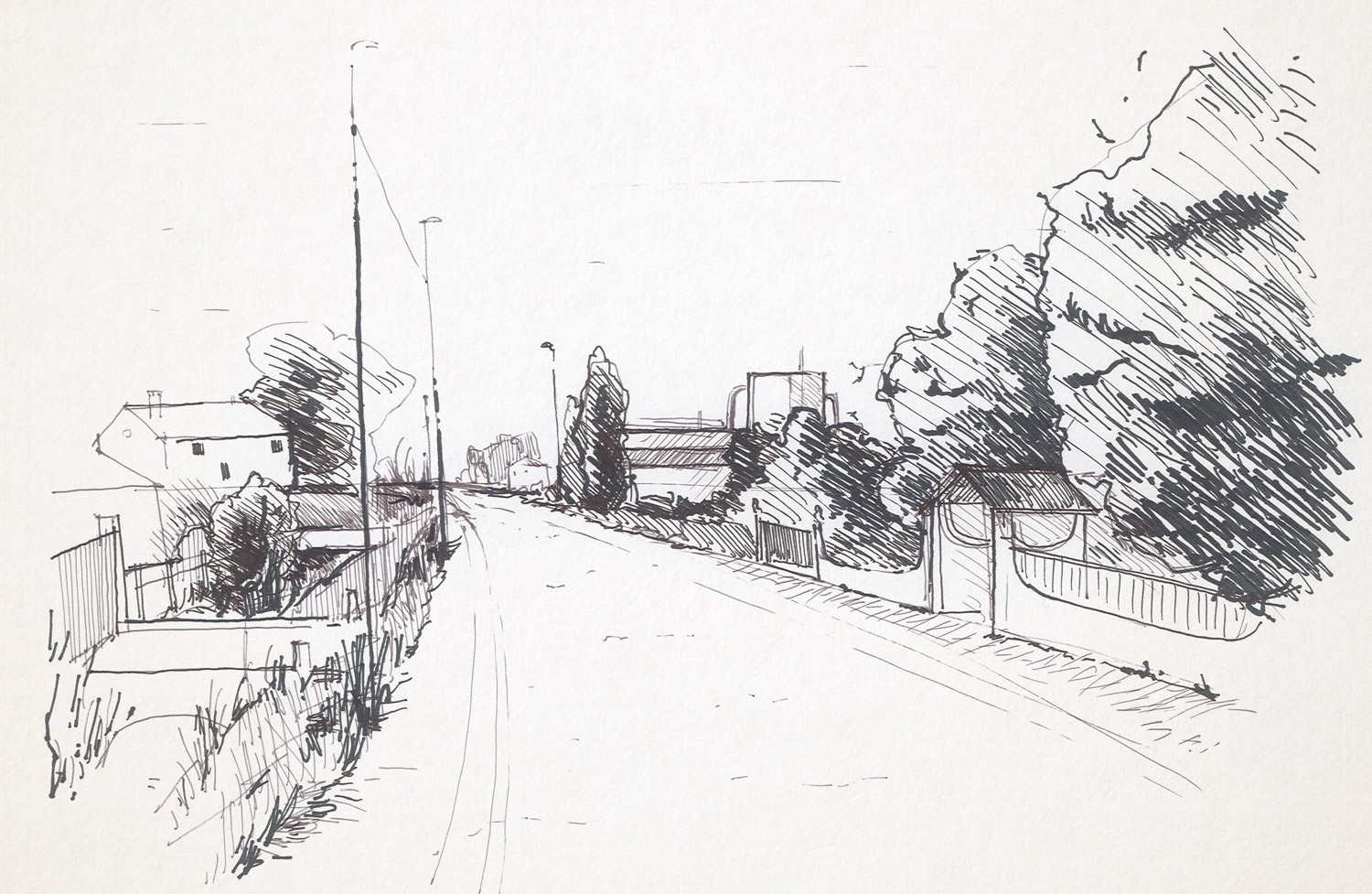

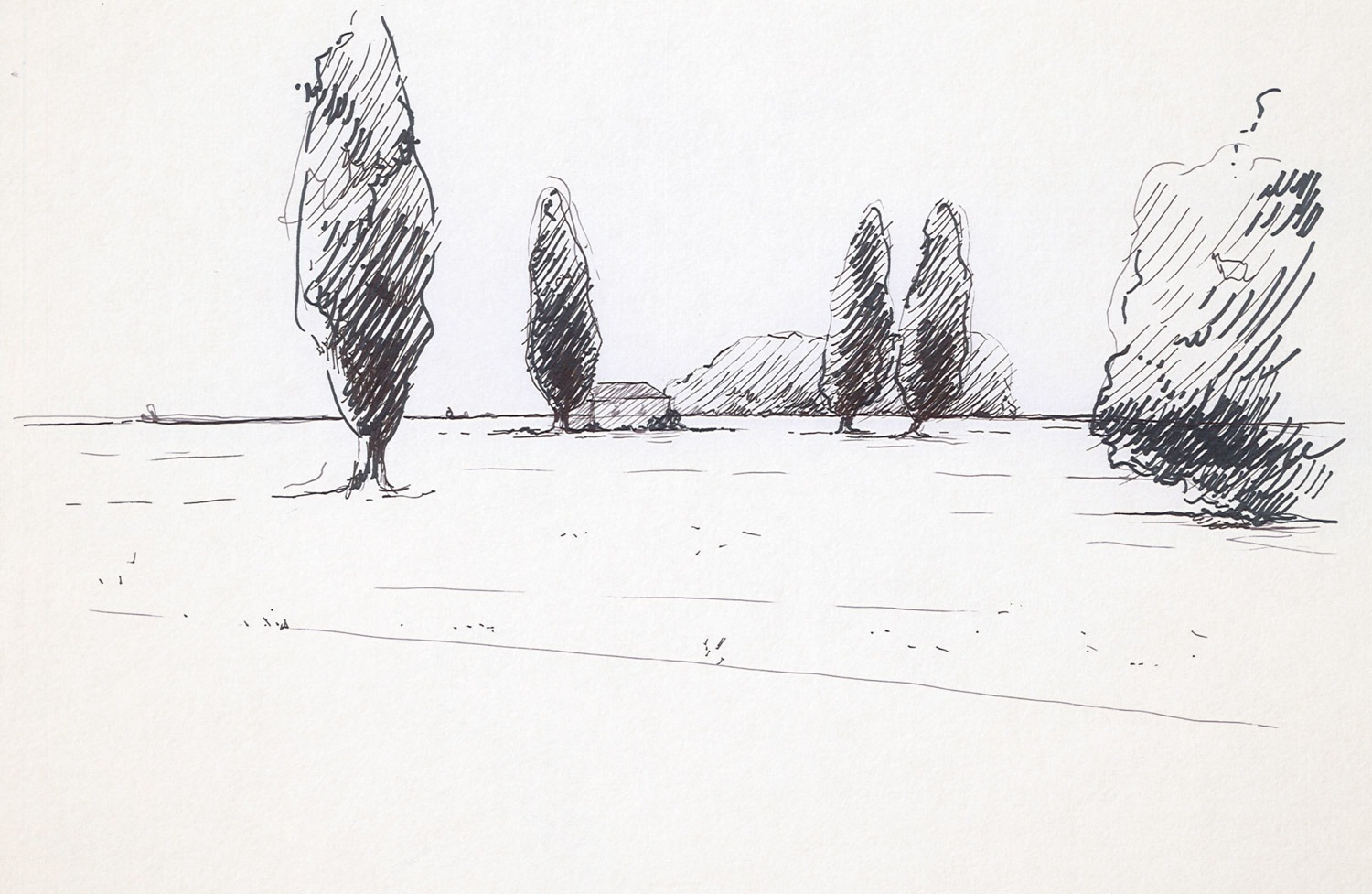

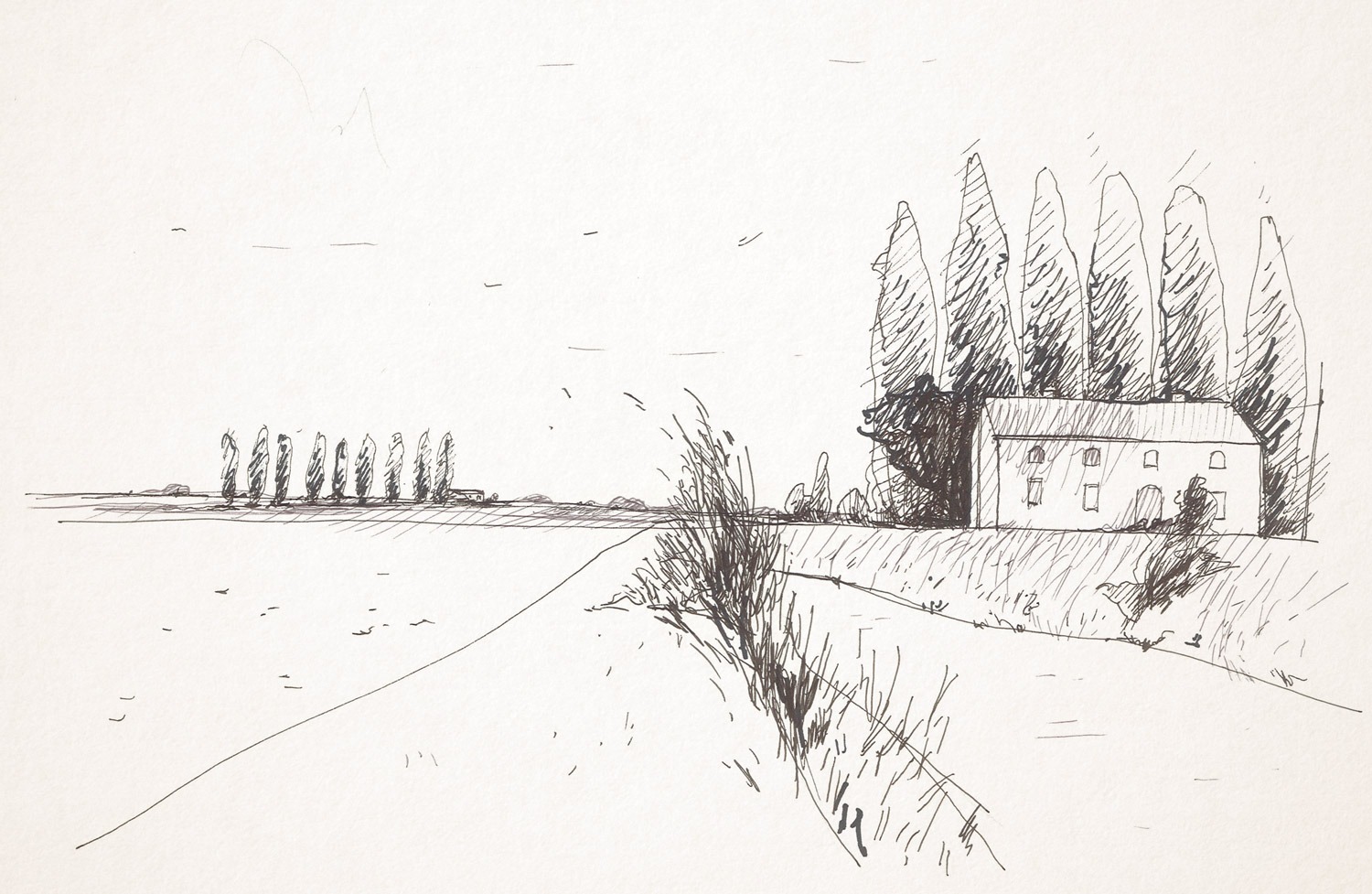

In Italy, the North East holds a strong place in the collective imaginary. As part of the country’s economic engine, it is an area of factories, family-run businesses, hangers and warehouses, interrupted only by the towns scattered around the land. Yet, the North East has a lesser-known image: that of the quiet, community life of its smaller villages. This month we turn to fiction for a glimpse and taste of this daily, local life somewhere deep in the Po Valley. In the Nort East is a sensory short story by filmmaker Giorgio Guernier, accompanied by drawings by artist Enrica Casentini.

A fly keeps hitting the open window over and over again, it doesn’t seem to hurt itself nor to understand it can’t get through. The buzzing noise – penetrating and inevitably annoying – wakes Dino up. It’s nearly 9 am as he opens his eyes and properly switches his hearing and sight on. Some birds sing from a line of trees not too far away while the sunlight makes its triumphant way into the room through the cracks of the tapparella. Dino gets up and moves towards the buzz. He swings the tapparella open so that the fly can take the party elsewhere. It eventually does. So long. Sleepy, Dino smirks, yawns, rubs his eyes and looks outside. Another summer’s day in Pianura Padana is about to unfold right before his eyes.

A few minutes later, Dino opens the kitchen door and enters. His grandma, a quintessential veneziana relocated to the country, greets him with a smile as she stirs the ragù. She demands a kiss. Her grandchild promptly abides – a quick peck on the cheek should suffice. Dino now takes all he needs for his breakfast and sits by the table. With a fetta biscottata in his left hand, he cuts a piece of solid butter and starts spreading it with a knife. Once again he ends up breaking the cracker in half. It happens all the time. He rolls his eyes and takes a sip of caffelatte to calm down. The taste of his grandpa’s homemade apricot jam is superb and the sugar promptly stimulates a train of thoughts. It’s the day of the Euro Final 1992 – Denmark vs. Germany. With Italy shamefully off the table, Dino has supported the modest, unassuming Danish team throughout the whole tournament. He now looks forward to the evening match.

At the age of 10 you’re already given chores in Pianura Padana, even if you’re a guest. Dino and his scruffy hair, freckles, brown eyes and timid stare that looks at the world with optimism, all venture into the town centre to buy the ingredients for Nana’s signature apple cake. The small shop where locals buy their groceries and inevitably end up chatting to Irma, the always smiley owner who was a partigiana and has blue benevolent eyes for everyone, is right by the church and typically busy. Dino, in fact, has to queue outside and wait his turn to enter. He looks at the provincial life surrounding him. He’s a city boy but has occasionally been around here for years. This village is a sample of Northern Italy from which you can see both the Alps and, if you climb to the top of the campanile, the sea. It’s a place of fog – so thick in winter che la puoi tagliare con un coltello1 – where the elderly have wrinkly hands and necks and hold their place in the world with dignity and serenity. There’s a group of girls in front of the church, they are Dino’s age. They are sat on a bench and comment on the passers-by as they chew gum and blow soap bubbles from plastic hoops. One captures Dino’s attention, he’s already seen her at church on Christmas day. She’s blonde, she has green eyes, freckles splattered all over her cheeks and a country smile that unintentionally makes you, a foresto2 from the city, weak in the knees. Her name is Alessia. Dino doesn’t know what love means or implies but he’s now questioning his heart for skipping a beat. A group of kids approach the girls and start chatting. Irma calls out for the next customer. ‘Oh you’re Letizia’s grandkid. Ciao, come va?’

The lunch is a triumph of taste, pasticcio à la bolognese with peas, potatoes, roast-beef, zucchine trifolate, mushrooms and Irma’s bread, the best of Pianura Padana, says grandpa. Dino is sat between his mum and dad, who arrived from the city just an hour ago. His grandparents sit opposite them. The adults talk about work, the tourist season in Venice, the possibility of buying a new car and other topics Dino doesn’t bother to try and follow. Grandma’s apple cake is served along with the caffè. The smell of coffee emerges from the moka when after lunch everybody around the table feels sleepy. Dino looks at the adults while they take their little white tazzina and stir their coffee with a teaspoon. It’s a ritual that involves sounds. The hypnotic noise of the spoon hitting the ceramic and then the gentle slurping. He drinks caffelatte every morning but apparently is too young for espressos. He shrugs when reminded, he will get there at some point.

While his grandpa opts for a little nap and his parents and nonna go sit in the living room to continue the conversation about their lives, Dino climbs the stairs and goes to his room. This is not actually his room – his room is in the city, next to his parents’ – but that’s the place where he sleeps while at nonni’s. There’s a single bed, a wardrobe, a mirror, a little frame with the image of Pope John Paul II, a painting of Venezia, Santa Marta and a large table on which Dino has drawn the markings of a football pitch so that he can have his smurf figures play on it. Dino lays on the bed and holds a copy of the local newspaper in front of him. Il Gazzettino offers an often self-indulgent view on Venice and its region, plus provincial news and bland features on National and International affairs, it’s the local everyman’s paper. For some reason while staying at nonni’s, Dino likes to borrow his grandpa’s copy of Il Gazzettino and read it. He understands that Democrazia Cristiana is still a big shot in the area but a new party called Lega Nord is breaking through. He also understands that one-third of Veneti3 are now self-employed. Dino is not sure whether he cares about all that, he’s much more interested in finding out that a local dog called Dandolo has saved a German child from drowning and an old man named Vittorio is currently travelling across the region on his tractor to visit his estranged brother who recently broke his hip. As for the sport, Il Gazzettino displays an entire page dedicated to the Euro final. As Dino reads the paper, he can hear the gentle snoring coming from his grandparents’ room. He’s never liked to nap and frankly can’t quite understand how someone can waste their time on such a tedious activity, but il nonno is old and apparently needs to recharge his batteries every afternoon.

It’s about 5 pm and the heat is much more bearable now. Dino grabs his bike and ventures outdoors. A strada provinciale leads to the town centre, a series of platani symmetrically planted at the edge of the road mark the way. These trees have seen sun, snow, rain, lightning hitting their branches and, where flowers are tied around their trunks, lethal accidents. Dino has always been impressed by those flowers, they mean death. There’s a solid big platano a few kilometres away, where years ago seven lost their lives. It was a foggy Saturday night. The families of those youngsters still mourn.

If you ride west, past the town centre, which is comprised of houses, a few shops, the church, the town hall and one pedestrian street, you enter a relatively new landscape, something that seventy years ago, when Dino’s grandpa was born, didn’t exist in those lands: an almost endless line of Capannoni,4 whose concept is very much tied up with the economic boom of the 1950s and ‘60s. Farms were quickly turned into little family-run factories. Some of them became huge and moved closer to the city, others remain local to this day, in any case, the impact of capannoni on the new northern Italian landscape is just astonishing. As their street posts testify, many of the newer companies bear names denoting hope for the new millennium and the continental union. References to the year 2000 and Europe are, in fact, very common. Dino keeps riding his bike and is now beyond the industrial area. He looks around and then up at the sky – it’s limpid with puffy clouds all over it. A plane flies fast from east to west. Dino, who has never flown but would like to, wonders where all these people are going.

Here’s the river, the end of Dino’s little trip, the place where many battles of La Grande Guerra5 were fought. It is the most celebrated watercourse in northeastern Italy, the symbol of the victory. There’s a few amateurs fishing and lots of birds flying or singing while perched on far-away branches, the whole picture looks like a celebration of pastoral life. A boat now crosses Dino’s vision, in it he spots an adult and two kids about his age, they look serene and undoubtedly happy to be alive. Dino sits by the river bench and looks around while the sun shines high in the sky many metres or possibly even kilometres away from him.

Dino sympathises with Gerhard Berger and Michele Alboreto, Udinese Calcio, Italian misfit Francesco Salvi, the ninja turtle Michelangelo, Wile E. Coyote and Weird Al Yankovic. He likes underdogs. It’s a no-brainer for him to support the Danish outsiders, now about to play their chances against the historical enemy, THE GERMANS.

It’s about 8pm and Dino sits on the sofa next to his dad and grandpa, who also support Denmark. The TV is a few metres away, a painting of La Giudecca Island is right above it. Two hours later the nasal voice of sports commentator Bruno Pizzul celebrates an astonishing 2-0 for the Danish underdogs. Take that, crucchi!6

While Dino’s mum helps her in-laws to wash the dishes and clean the kitchen, Dino and his dad go to the town centre to buy anguria.7 A small pedestrian street goes through the town centre – as you walk down it, you can hear the audio of different TV programmes blaring loudly from open windows, it sounds as though they are at battle with each other for the dominion of the night. On the sidewalk, a few elderly people sit on foldable chairs and talk about the heat, cholesterol, WWII, the new young vicar who comes from the city and has a lovely baby face, their grandkids who are all good students and their grown-up children who now have car phones and fax machines. They drink red wine and look at each other with intensity and benevolence, they are in this together.

At the end of the pedestrian street, is the church and in front of it is a stand that sells anguria along with cotton candy, ice cream and drinks. There’s a small queue and Dino and his dad obediently join the end of it. After a few seconds, a chubby middle-aged woman passes by and positions herself right behind them. She smells very good, a perfume that vaguely resembles Dino’s mum’s but a bit different, more rose-y. Dino likes it, for some reason he thinks it goes perfectly with the smell of cotton-candy. The woman calls out for her daughter: ‘Alessia’. Dino looks around and now sees the green-eyed blonde. His heart skips another beat. She walks towards them and is now close to her mum. Dino looks at Alessia while hints of her mum’s perfume and cotton-candy reach his nostrils. It’s a weird but very pleasant combination of audio-visual material right here. Alessia looks at Dino, he can’t handle it and looks away. Now it’s their turn. The man behind the counter speaks the local dialect, Dino’s dad responds using the same tongue. It’s a quick transaction, they’ve been served and have to move on. They step aside. Feeling somehow safer, Dino looks back at Alessia, who reciprocates the stare. He finally finds the guts to bear that astonishing sight and even smiles. Alessia smiles back until her mum asks her if she wants ice cream. ‘Come on’ says Dino’s dad at the same time. Father and son leave with an entire anguria tucked under Dino’s dad’s arm. While walking away, Dino looks back at the stall but Alessia and her mom have already gone. The smell of cotton-candy still glides through the air sweetly.

The anguria was excellent, refreshing and sweet. The usual hugs and kisses are now given to the nonni and the young family is soon on its way to the city. In the car, Dino lays flat on his back in the backseat. From that perspective, the only things he can see are trees, the sky, the moon, company street signs and electrical wires that run intermittently from one electricity pole to another. Houses too. While thinking about his summer’s day in Pianura Padana and ultimately about Alessia, he continues to stare outside – trees, wires, pole, trees, wires, pole, sky, moon, clouds, houses, company street signs, trees, wires, pole, trees, wires, pole. It’s a small perspective on the world and it can only draw upon 10 years of experience. Dino shrugs and smiles. He now closes his eyes and smoothly slips into simple dreams.

Footnotes

[1] So thick you can cut it with a knife

[2] ‘Foreigner’ (not from the village) – Venetian term

[3] People from the Veneto region

[4] Hangars

[5] WWI

[6] Italian for ‘krauts’

[7] Watermelon

Images © Enrica Casentini

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »