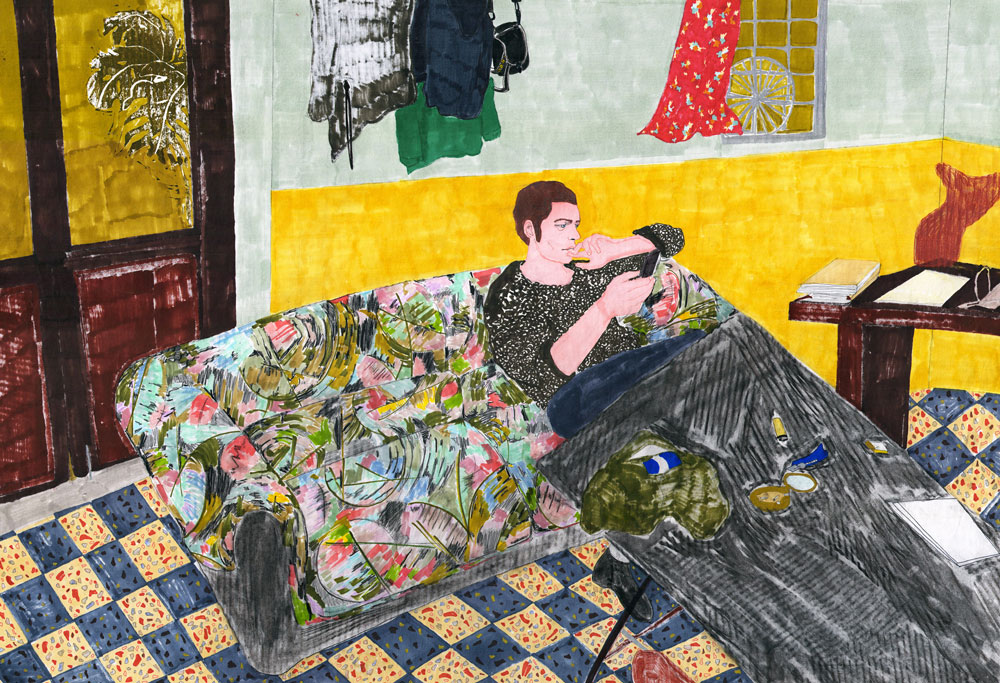

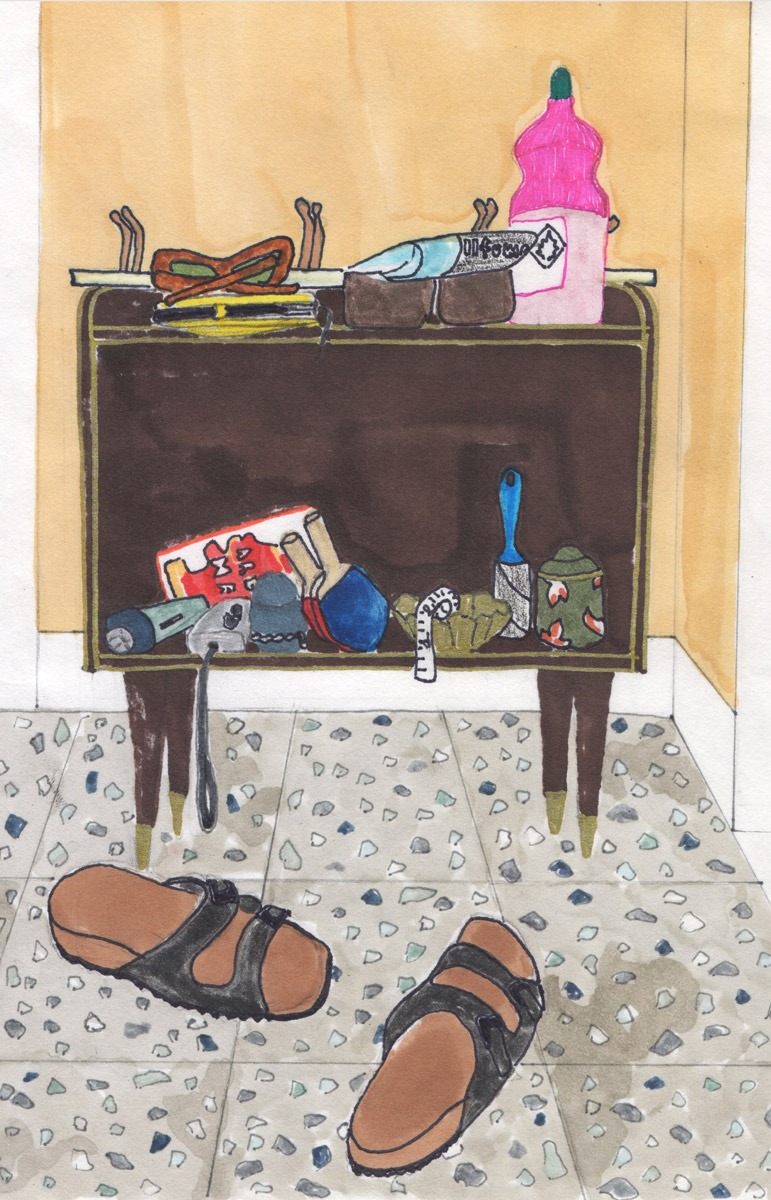

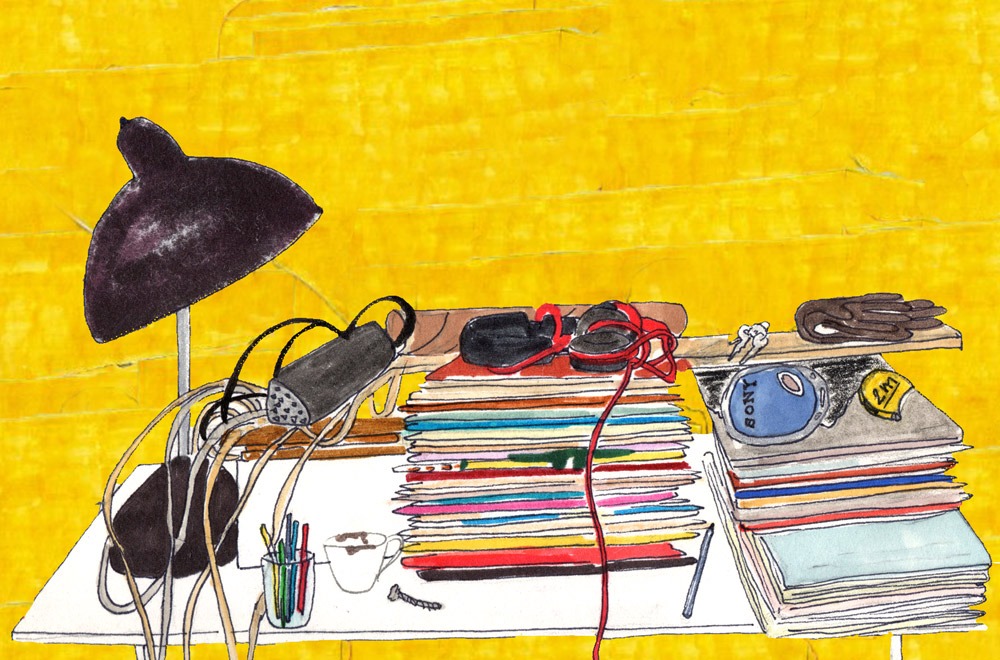

In these times of enforced self-isolation, the objects that once constituted the discrete backdrop of our home start to be seen in a different light. In this intimate contribution, radio producer Jonathan Zenti tells us about how being quarantined in one of Italy’s most affected cities has brought his previously overlooked relationship with mess to the foreground. With images by illustrator Susana Ljuljanovic, from the series ‘Habitus’.

My apartment is a mess.

I got a text last week from my friend Diambra, a photographer living in Barcelona. She was scraping the grouting between her floor tiles with a toothbrush. I’m not that kind of person, I never found any value or pleasure in tidying or cleaning up, but I always do my best to keep some order in case someone pops by. But this unexpected quarantine is revealing a truth that I’ve always known: when my social habits are restricted, the mess I naturally produce takes over my personal habitat like nature regaining control of abandoned industrial sites.

I look at my mess now, making an imaginary POV movie shot with a dolly going wider and wider. I start from the screen of my laptop that is full of stains and dust. There’s a dark brown spot on the lower corner on the right, that comes from some coffee I spilt on the keyboard a few days ago. There’s a pen drive that’s been inserted there for 2 days even though I’m not using it. On my right, just next to my elbow, there’s a small cup which I drank a coffee from three hours ago, and a bowl from which, just before the coffee, I had a banana with yoghurt for breakfast. On my left, I can see my slippers in the middle of the floor (I’m wearing shoes right now).

The rest of random things on the table, from left to right, like a politicians’ group picture: a hard drive with a backup from 2012/2013 that I checked last week, a chocolate/hazelnut cream cup almost empty (with its cap on, at least), headphones that I use for video calls, another hard drive that’s here just because it lives in the same box as the other one, a glass bottle with two inches of water, a cup for the yoghurt I had as a snack a few minutes ago, a used tissue, the sugar jar, a bottle of coke, half-empty, a table stand with a microphone on it, an audio interface and a couple of cables, a folded table mat, another pair of professional headphones, a notebook and a couple of those gummy wires that are used to close bread packages.

Under the table there are three pairs of shoes: I wear them at home during the day and then in the evening, when I’m tired, I take them off whilst writing or watching videos, and I leave them there. On my left, there’s a long shelf connecting the kitchen/dining area with the living room (it’s the same room, with a short wall dividing the two areas) and on the shelf there’s a pile of mixed-up stuff that has been thrown there for weeks, from invoices to records to wires to receipts: It looks like a long fast-food sandwich when you try to put as much as you can in it. Then there’s the couch that I never use because I work at the kitchen table and I lie on the bed if I want to watch a movie or an episode of a TV series. On the couch there’s my winter jacket, scarfs and a beanie. I haven’t used them for two weeks since it’s not that cold anymore.

And there’s my spring jacket over it, a baseball cap and a light neck-warmer that I use as a face mask when I go to do my groceries. There’s also an Ikea rainbow bag that I use to gather laundered clothes. Between the couch and the shelf, standing enthroned like the king of self-abandonment, there’s the clothes horse, where my underwear, socks, t-shirts and hoodies are left. Not until they are dry, but rather, until I need them, forcing me to dance a ballet around it when I need to reach the bathroom to go to sleep. It’s a move that brings to mind a scene from “Gummo” by Harmony Korine, where the mother of one of the main characters brings a tray with milk and spaghetti to his son whilst he’s having a bath, and she walks through an astonishing mess in the hallway as though it were a dance she trained for everyday.

I stop the POV shot here, with a deep focus on what I can see through the bathroom door: towel on the floor, and another messy sandwich of dirty clothes, toothpaste, deodorant, lotions and other random stuff (it’s important to note that there’s an actual dirty clothes basket in my bedroom, but I’m clearly too lazy to take them there after I shower).

I’m looking at this mess the same way we look at a friend during a goodbye. I know this is the last day, that it is too much, and that tomorrow, if not even today, I’m going to tidy up my personal, intimate new environment.

It’s the 26th of March and I’ve been at home alone for a month now. Exactly one year ago I was living in Rome, organising a move to the more vibrant Milan and going nuts trying finding a room through phone calls and internet posts. Suddenly, a friend of mine told me that he had a lead for a flat: it was affordable and roomy, but it was in a basement. And it was temporary, the owner had plans to turn it into something else sooner or later, but at least one year was guaranteed. I said yes, I thought it would be easier to find another room or flat whilst already in the city.

So now here I am, in this once-fancy 2 bedroom flat with a kitchen corner, with three barred windows that start four inches (or 10 centimetres) above my head. To look outside I have to get very close to the wall and look up: I usually see dog testicles, ladies calves… From time to time a kid stops and looks at me as if I were Pennywise in the manhole. If I leave the bedroom and the living room windows open, there’s a pleasant current that brings in fresh air very quickly.

The quarantine condition seems to be the right chance for all my friends and family to finally deep clean the house, wash the curtains, throw away dresses taking worthless space in the closet, sanitise even the most remote corners. Amongst the many feelings that are surfacing during this surreal self-isolation, there’s the one that tells me that there’s no need to make things right in here: nobody is watching, I’m allowed to be wrong. So why is being wrong feeling so right to me, now?

One of my best friends, radio artist Kaitlin Prest, put me up twice. The first time was 4 years ago and she gave me access to her place in New York while she was away; the second time was last month and we basically lived together for a week in her studio apartment in Los Angeles. Both times, her living space was a mess, she didn’t bother to clean it up before I went, and I didn’t bother to find that mess when there. I sneaked into her mess like a caterpillar creating its cocoon between layers of leaves. I felt warmth, both times. A few years later, I put her up at my house in Verona for 3 weeks; we weren’t that close at the time and I was concerned about keeping the apartment clean and tidy. And she kind of told me off. She introduced me for the first time to the pride of the messy mess. She told me “why should someone who keeps it clean and tidy all the time be considered a better person than I am? What’s the moral difference?”. Frankly, I didn’t have an answer for that, and I don’t have it now.

I grew up in mess. My grandmother was already too tired to teach someone else how to keep it clean when my mother was born as the fourth child, and my mother was too young when she had me to learn how to do it and to teach it to me. As soon as a tiny stream of money came into the house, it was immediately invested in a cleaning lady who would iron and clean twice a week. Nobody has ever taught me how to clean and, most importantly, nobody has ever taught me why it should matter. I still don’t get it. Tidying up was only present in the imperative command “Tidy your room up!” as a punishment or as blackmail to keep me under control. I only started to clean in earnest when I moved to Venice to attend the university in 2001.

There were two reasons for this: firstly, there were some house rules to follow, secondly, I felt bad for my roommates if I didn’t do it. They were tidier than I was and I felt guilty. I don’t know if I did it right, but for sure I did my best. Later on, I started to see it as an emancipatory practice because I didn’t want to repeat my parents’ mistakes. But clearly it has never come naturally to me.

What this self-isolation has revealed is that, basically, I clean for others. For my guests at dinner, for the woman I think might sleep-over, for my landlords. It’s never for me. Or, at least, never to fulfil a personal need to see the space around me in order. In fact, I hate order in all its shapes. The only time I stand up and clean for myself is when I feel I’m letting it go too much: it’s usually around the time when I cut my beard or my hair. It’s like a sword stroke to the depression that is trying to get me for good.

Self-isolation has therefore made clear that all the objects that slowly rearrange the aspect of my home, have a life of their own, an organic life, that echoes the progress of my rollercoaster of feelings. Likewise, the silence and honesty of loneliness have revealed the “gardener” routine that accompanies my relationship with mess. Normally, roots are growing around me from Monday to Friday. Saturday morning I cut them and Sunday is the only day of the week where everything stays put. Inevitably, this routine gets suspended every time I fall into the anxiety of my creative process: stuff starts piling up around me until the craft is over since I can’t really think about anything else. So nature returns, reclaiming its space.

It’s been more than 20 days now since I’ve had no guests, no dates, no landlords showing up. Having cut my daily walk out of my routine, along with the movies and coffees with friends, for me living in this basement flat with barred windows feels like rolling about in an empty grave that is slowly filling up. I’m unequivocally “alone”, surrounded by all these footprints of myself that testify to my being alive. Tidying them away will be like severing some natural parts of me, waiting for them to grow again.

Images © Susana Ljuljanovic

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »