Access

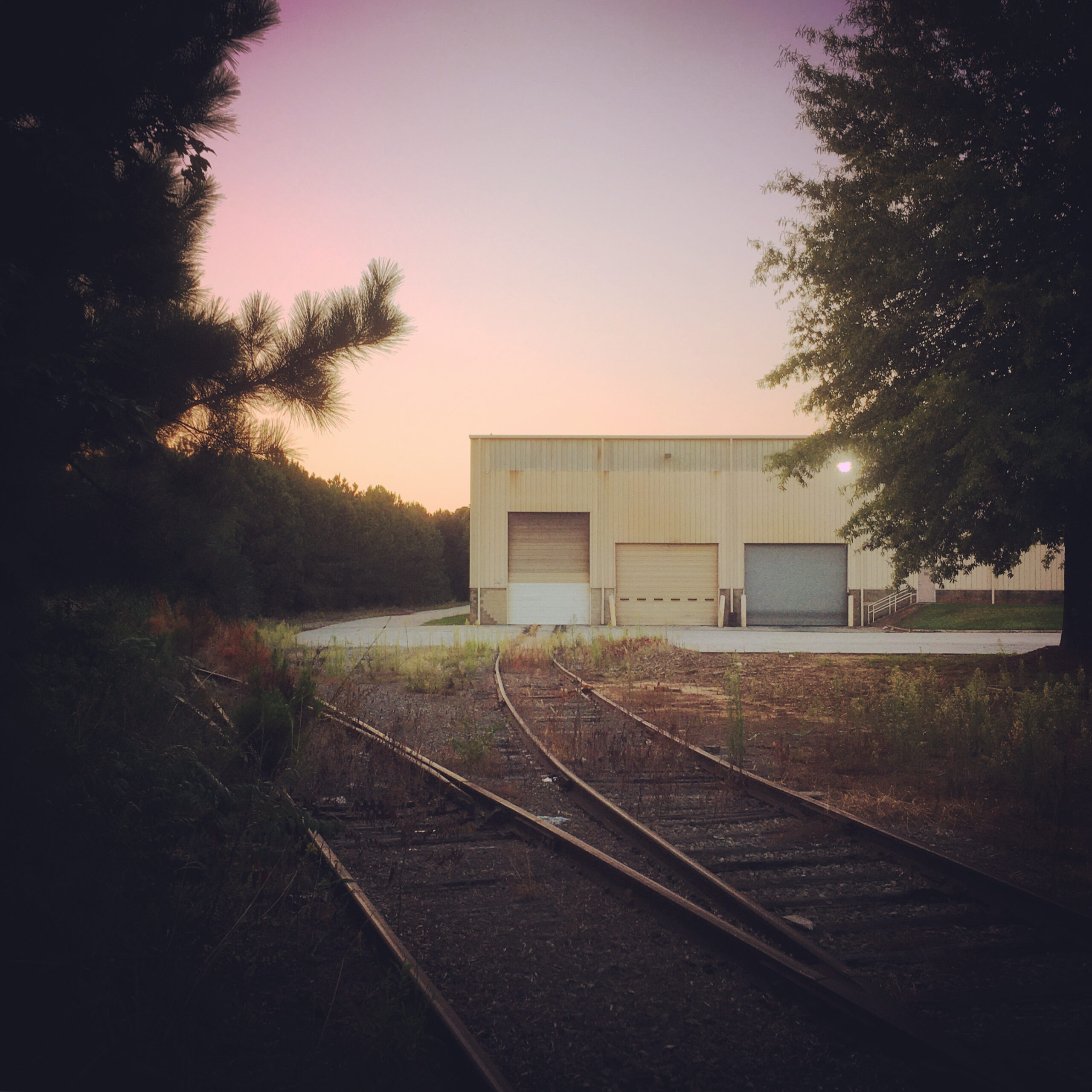

Spaces can work like archives, where access to information is granted or protected depending on the institutional frameworks at play. Resulting from the author’s runs in lockdown Atlanta with only a phone at hand, this photo essay by Ryland Johnson gives us glimpses of shut-down corporate areas and warehouses which he came across serendipitously, and that prompted new reflections on our daily reading of spaces.

Native Lands Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the traditional and unceded territories of the Cherokee, Creek, and other Indigenous peoples in the Metro Atlanta area, and also the many Indigenous peoples of Northwest Louisiana, including the Caddo Nation and the Choctaw Nation. These lands have been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years and continue to hold great cultural, spiritual, and ecological significance.

These Nations, as well as others, were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in the early 19th century through policies like the Indian Removal Act, a federal law that aimed to relocate Native American tribes to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. This forced relocation is known as the Trail of Tears, where thousands of Native Americans died.

I also acknowledge and pay respect to the Indigenous peoples who continue to live, work, and care for these lands today. We are grateful for the opportunity to share their stories and to learn from their perspectives.

As I present this photo-essay, which was composed on these lands, I hope to contribute to a broader understanding and appreciation of the rich history, culture, and contributions of Indigenous peoples.

Access

‘Access’ is a concept of particular importance to librarianship, so much so that it functions as one of the modern library’s core values: ensure access for all. In librarianship, the broad concept of access refers to the ability of users to freely locate and obtain objects of information. This includes both physical access to ‘real’ objects of information and electronic access to digital resources.

Traditionally, these objects of information are housed in a library or an archive, within some controlled, interior space, to which access is granted. Yet it isn’t difficult to imagine the definition of an informational object more grandly and more comprehensively, as being something unconstrained, or something existing beyond the confines of library walls. Already there is the notion that services of public benefit fall squarely within the mission of the modern library, and that these services are in their own way informational objects to which the people have a right to access.

I was living alone then. I have diaphanous memories – on one hand, there is a yawning absence, an untraceable emptiness of being without content. I know that time passed; but, it has spun out of my reach. So much of the lockdown – what I did, what was done – is inaccessible to me, lost from my memories. On the other hand, there are so many clear moments, disconnected images of the discrete details of doings and activities: sewing masks from canvas bags and old jeans, social media, obsessive sanitation rituals, news, games, organisation, computer work, virtual conferences, and relentless exercise. All of it, done on my own.

My modest one-bedroom became fortress and prison, sanctuary and jail. I would escape in the evening when the light began to change and the air cooled, running for miles in any direction, changing my route as much as I could, chasing novelty in my solitude: a new street, a new passage, a new place. My daily run was an ascetic origami of emergent pathways.

When someone came running toward me, I would cross to the other side of the road. I preferred to run away from the peopled spaces. The public parks were overfull, and while I appreciate looping paths and simulated nature, at that time it was anxiety-inducing to run amongst so many humans. Neither did I much enjoy running in the neighbourhoods. It was too upsetting to my class sensibilities. I remember the sharp question of how it was possible for anyone to afford so much space echoing in my mind. I could barely afford an apartment in the community I served, a tiny box stacked among innumerable identical boxes.

Here were lawns and garages, homes as large as my whole block. Here were threatening signs, fences and gates, pathways blocked, routes closed, vast spaces into which no one ought dare go where all that lived was grass. Here was an altogether restrictive world, made uncomfortable and inaccessible by the power of private property to create boundaries, insiders and outsiders, haves and have-nots. I remember one night in particular. I ran to a lake and saw upon it in the distance a throng of wealthy boaters. I could hear their laughter echo across the water beneath the crackle of their fireworks, so flagrantly rapt in their masque of the red death.

Access to library materials may be restricted for a variety of reasons, such as copyright, preservation, or security. Librarians and other information professionals work to ensure that patrons have access to the information resources they need, whether that be through traditional means such as catalogues and reference services, or through information and media technologies like online databases, e-book lending, apps, and so on.

While reasonable restrictions on particular objects of information may exist in necessary cases, such restrictions are often mere exceptions to a more fundamental rule: ensure access for all. Access conduces the library’s welcoming posture towards the other. The library welcomes the other in. Its collection is not its property, nor its space, or its chairs and tables, its cooling system, its heat, its bathrooms. The library is for all of us spatially, wholly, not just a collection of informational objects, but as a place, a touchstone, and a foundation for community.

I found myself running the highways and the big streets. They were deserted at first. For a short time, I could run down the middle of the road for miles.

I ventured into the industrial parks and corporate villages surrounding the highway. There I found a vastness of a different sort, a paradoxical safe wilderness of empty places. I found impressions left by an absent humanity in these utterly useless workspaces – stark loading bays and enormous parking lots, and ridiculous picnic benches that no one ever used anyway.

There were anonymous offices with black, mirrored ribbon windows. Massive warehouses with enormous bays open to the wind. Topiaries and utilities. Strange shrines inexplicably placed. Parking decks of sloping concrete. Loading docks. Ornamental trees blooming for no one. Security cameras recording nothing. Stillness. Free air. Open quiet.

In librarianship, the concept of finding refers to the process of locating and retrieving objects of information. Finding can take place with or without the help of information professionals. It can include searching for books, journals, articles, and other materials in a library’s catalogue or online databases, as well as navigating the library’s collection in the real world using intimate knowledge and classification systems like the Dewey Decimal System. That an object of information is findable is primary to its existence; if an object of information cannot be found, it does not exist informationally.

Serendipitous finding is a special kind of finding that only ever happens when one is on one’s own. It is characterised by the spontaneous discovery of objects of information as a result of free flow and wandering through a collection, and by the emergent and unexpected usefulness of the found informational objects. Serendipitous finding is both embodied and environmental, magical and mundane. It reminds us that the unpredictable and the unexpected emerge even in the most rigorous academic confines, and that research resists control. It also suggests, almost as in a conjuration, that positive outcomes are produced by the library itself, and that the collection is writing itself.

I let myself flow through the empty places, attuned to the unexpected, welcoming the fortunate, drifting further into the hinterworld, in search of images, places, and feelings.

These banal office parks and sterile industrial zones were not built for this. They were not built to encourage serendipity. They are the predictable products of capitalist urban planning, designed to control and manipulate worker behaviour, placed for maximal connectivity and profitability, and responsible for the inevitable feelings of alienation, boredom, and apathy. Yet, exorcised of the ghosts of work, they were welcoming to me, and, in a way, each park was its own collection, each one organised, orderly.

All the docks were numbered, as were the entrances, the buildings, the parking spaces. The warehouse facades were a catalogue of minute, bespoke variations. All the sitting areas and utility meters seemed arranged in such a way as to produce hidden meanings in particular organisations, in a hedge or a tree, or a wall of glass, or a sign, or a door. Balanced and unbalanced compositions. Symbols without words. Like closed books, their contents obscure, once opened unfold a profound transformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on librarianship and the way that libraries operate. During the lockdown period, nearly all libraries underwent some sort of reorganisation to comply with social distancing measures and other public health guidelines. One lasting benefit of this is that libraries are more prepared and mindful of ways to provide virtual access to their collections, as well as access to services for users who are unable to physically visit the library. Overall, the pandemic accelerated a shift towards a more expansive view of the library in today’s world, a view of the library without walls.

The typical iteration of “a library without walls” has been with us since the 1970’s. It is merely an analogue for digitised text, and it carries with it all the original optimism and insanity that the internet as a new technology brought. It is the dream of a total digital archive, complete and filled with everything. Like classic science fiction, imagine all the world’s knowledge in the palm of your hand. There is something that is indeed aspirational here; but, unfortunately, access in this mode must still conform to traditional power relations à la, an on/off switch and a paywall. It is access that is easily denied or withheld. It is static and subject to authority control.

The more challenging aspect of the library without walls is to consider the world as its emergent collection. Here we glimpse wild access. Here, access is a potential for the disruption of normal patterns of behaviour and perception. Wild access allows us to engage with our environment to create a more livable and authentic spatial reality. It illuminates how the natural and built world leads our experiences toward certain ends, but also reveals how we might transform those ends. It reveals that the world itself is informational and worthy both of finding and of preservation.

Beyond providing access to informational objects that are not traditionally considered part of the library’s collection, beyond zines and seed banks, tools and beekeeping supplies, beyond indigenous languages, oral histories, underground records, and secret knowledge – beyond all these manifestly good things, things which each vitally and creatively expand the library as a true public good, wild access reminds us that places ought to be free too – free too to exist.

It was strange, but the thought often came to me when I was searching these spaces: what would I say if the police came? I spent a lot of time in those empty zones imagining what I would say to the police, but there were never any police. It was just me, alone.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »