In 1964, British engineer Rod Rhys Jones set off to Antartica to conduct work for the British Antarctic Survey. Fifty years later, he found himself back there installing a monument to commemorate those who lost their lives in the pursuit of science within this harsh environment, including three of his own friends and colleagues. In this intimate, autobiographical piece, illustrated by the author’s own paintings, Rhys Jones recalls that year, his impressions of Antarctica and the placing of this remote landmark.

The Antelope

I was sitting in the bar of the Antelope just off Sloane Square in London, 1964, watching the evening beer go down and talking to a college friend about my prospects after my civil engineering degree. I had been offered a job building the M1 motorway in Yorkshire and another – more attractive – building a Hilton Hotel in Tehran. But I was looking for somewhere even more challenging, something that would really test me.

“How about the Antarctic?”, he said. I had studied surveying as part of my degree and he reminded me that my tutor, ‘Steve’ Stephenson, had made maps in the Arctic and the Antarctic. With hazy images of the blackened frost-bitten hands of John Mills in Scott of the Antarctic and the account of The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry Garrard, Antarctica began to beckon me. It was an opportunity to go to the last place on earth marked “unknown” – to fill in the map with the mountains, valleys and hills, waiting to be discovered.

Within a couple of days, I found myself in the small, crowded office of the British Antarctic Survey, BAS, in Gillingham Street, behind Victoria Station. It was filled with stores and equipment, anoraks, large indeterminate boxes, theodolites, sleeping bags, food boxes, skis, sledges and more. A place of bearded men with relentless good humour. A place marker on the path of discovery and exploration. I volunteered to update the map of the city of Stanley, the capital of the Falkland Islands. Leaving London early, I would spend three months there before heading further south to Antarctica. Little did I know that 50 years later I would be back there, installing a memorial ‘to those who lost their lives in Antarctica in pursuit of science to benefit us all’ on that very same waterfront.

The Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are long and low with sandy beaches peppered with penguins backed by sage-grey tussock grass through which sleepy seals roll and throb their gaseous claim to their beds of stinking vegetation. Stanley with its population of a thousand souls was the advance base for the British Antarctic Survey. Here, explorers were kitted out, receiving two large brown canvas bags for their clothes – shirts, sweaters, socks, long johns, anoraks, rough purple tartan shirts, mukluks and for me, size 13 leather boots. Silk gloves for instruments and woollen gloves for warmth, felt and leather mittens for protection. Nothing left out.

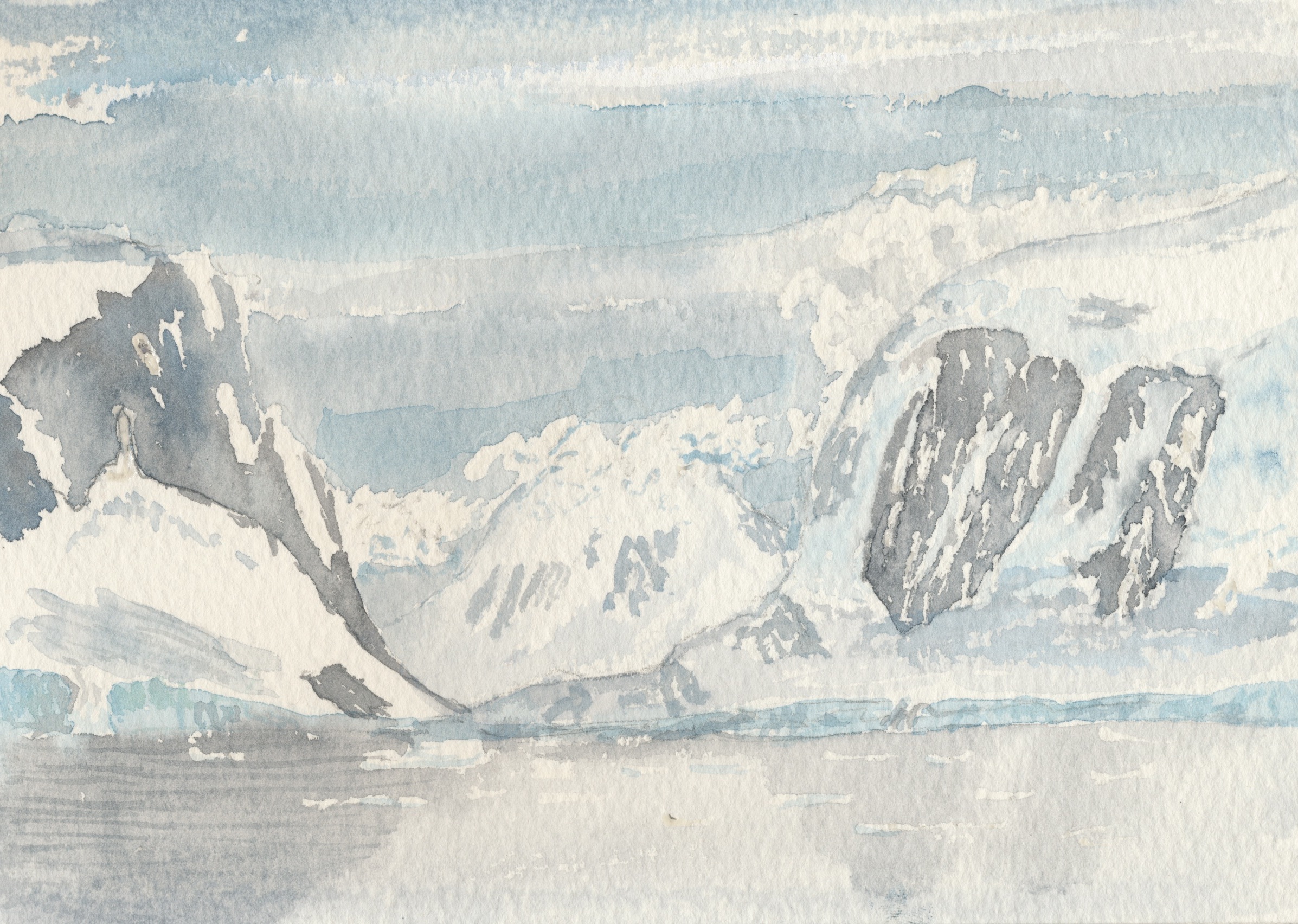

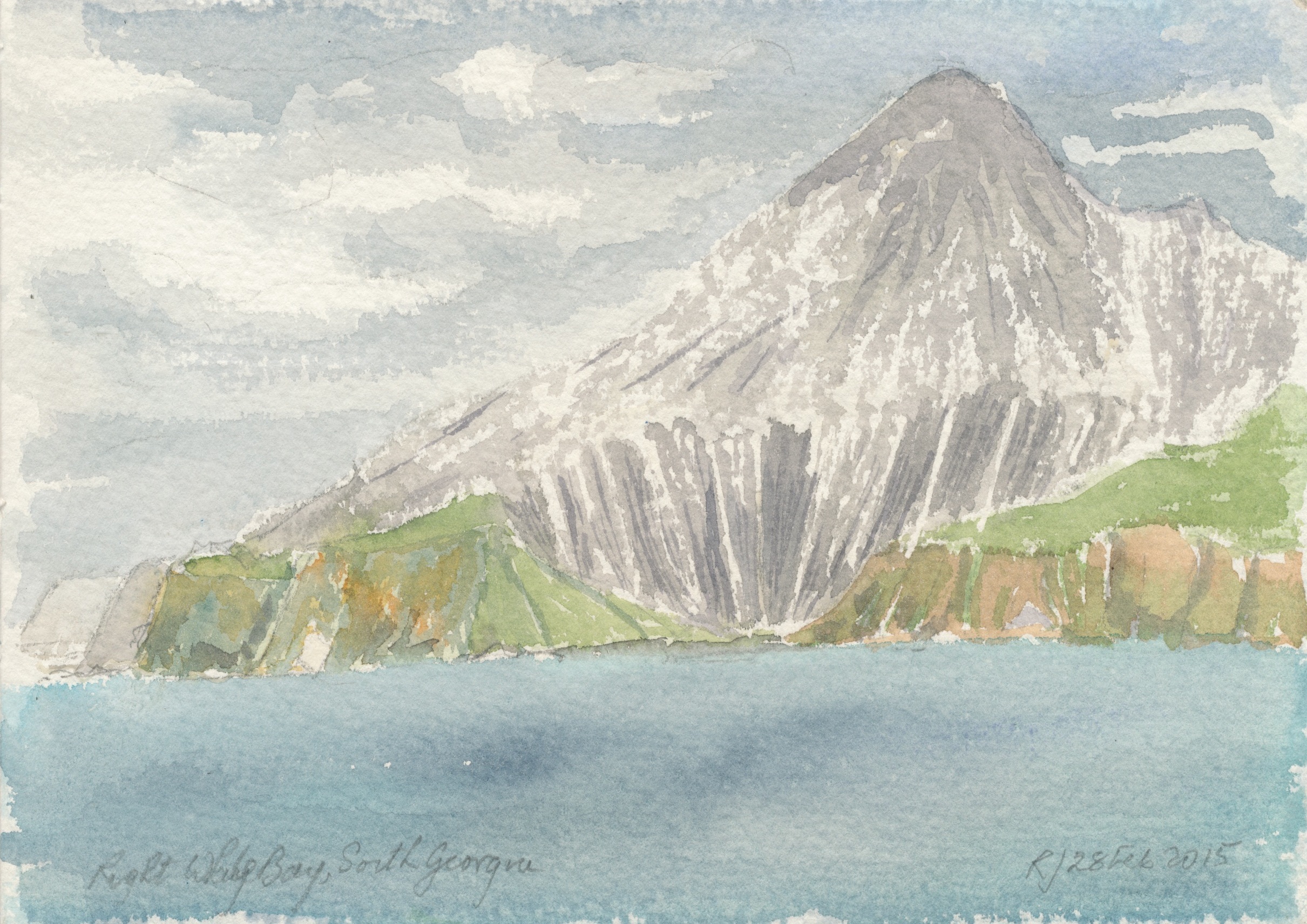

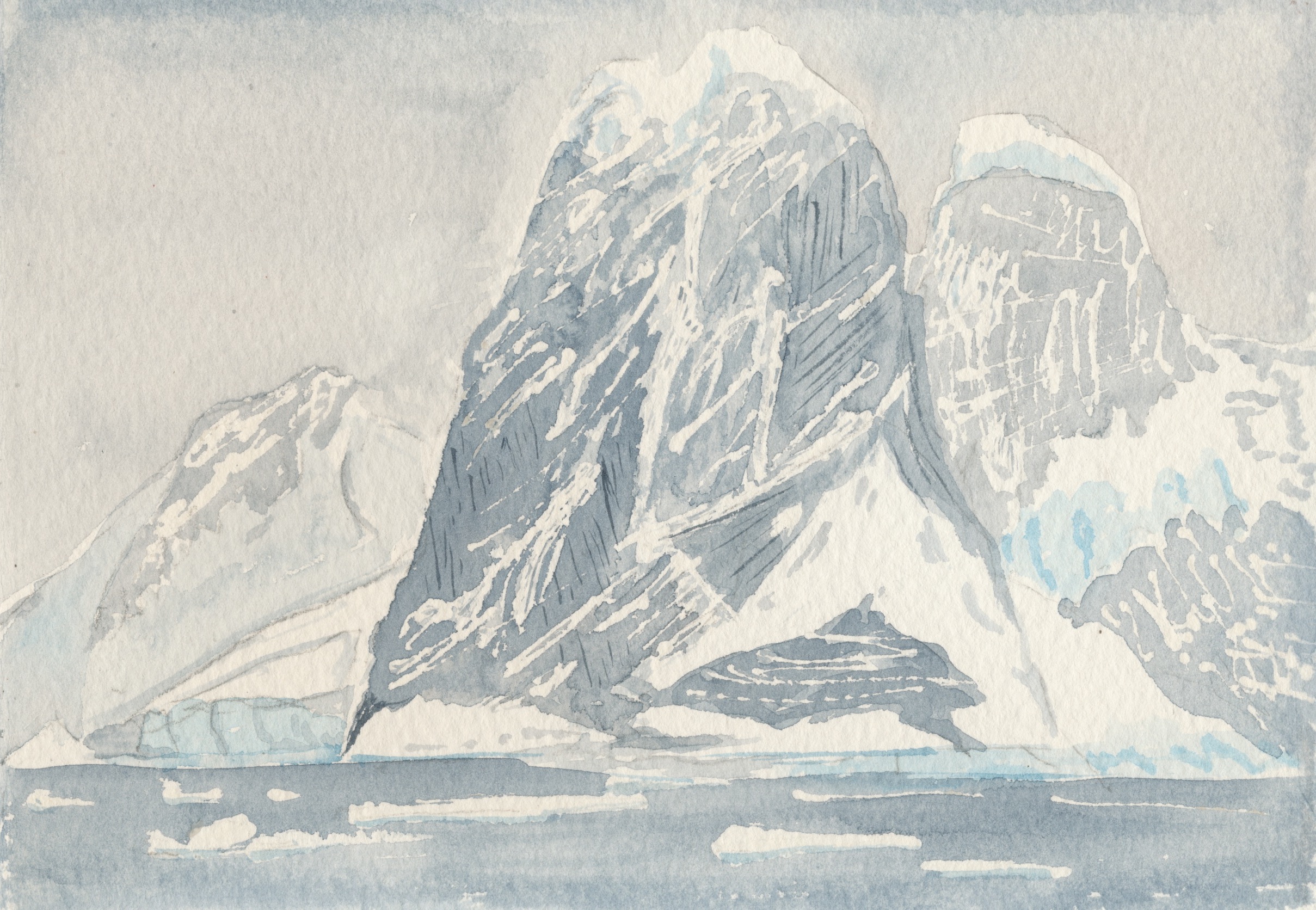

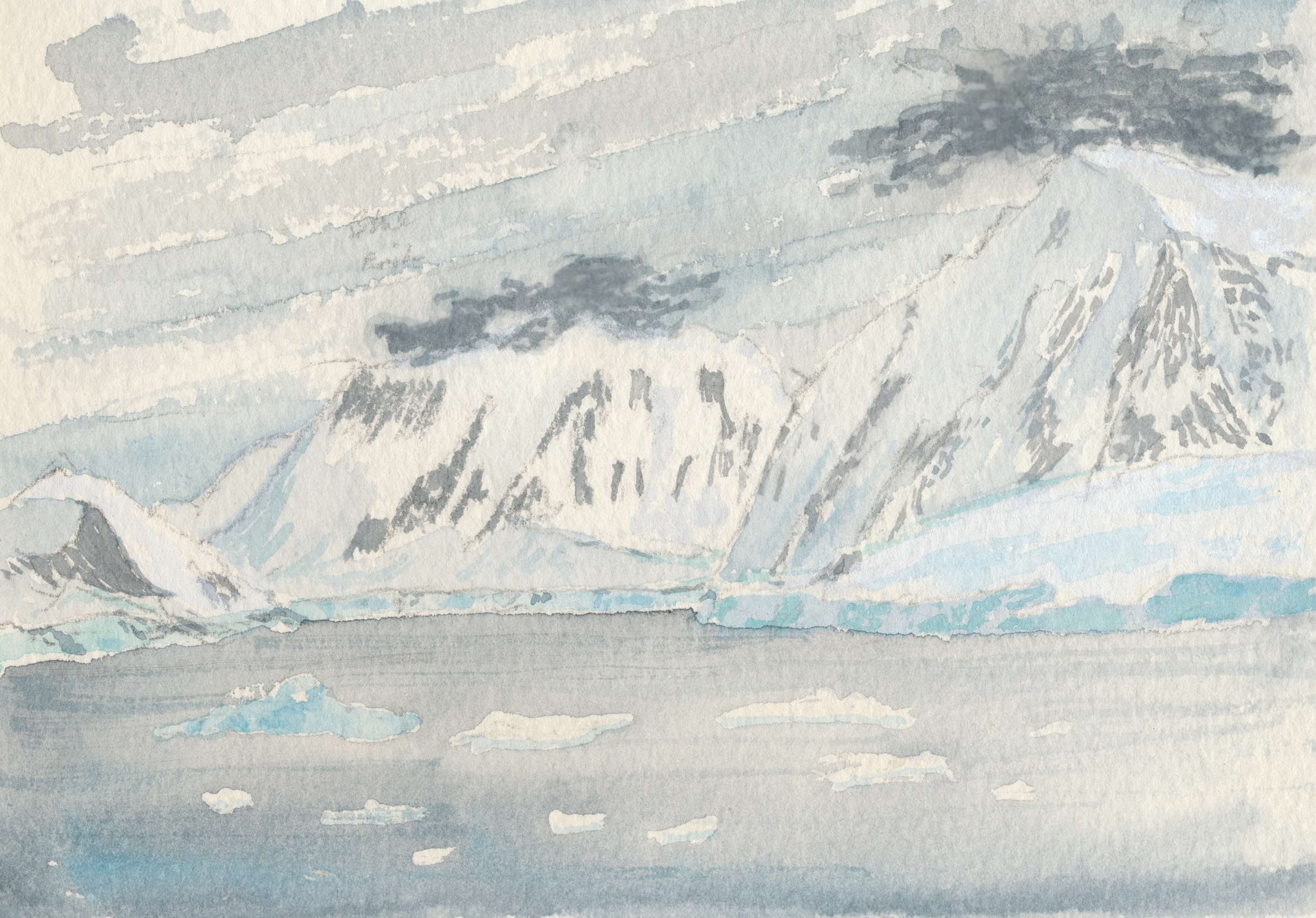

Right Whale Bay, named after the whales that gathered there. Right because they are slow moving and float when killed. A brutal reminder of South Georgia’s whaling past. Top image: Towering cliffs and ice fields appear to be blocking the way south in Errerra Channel – but It is an illusion.

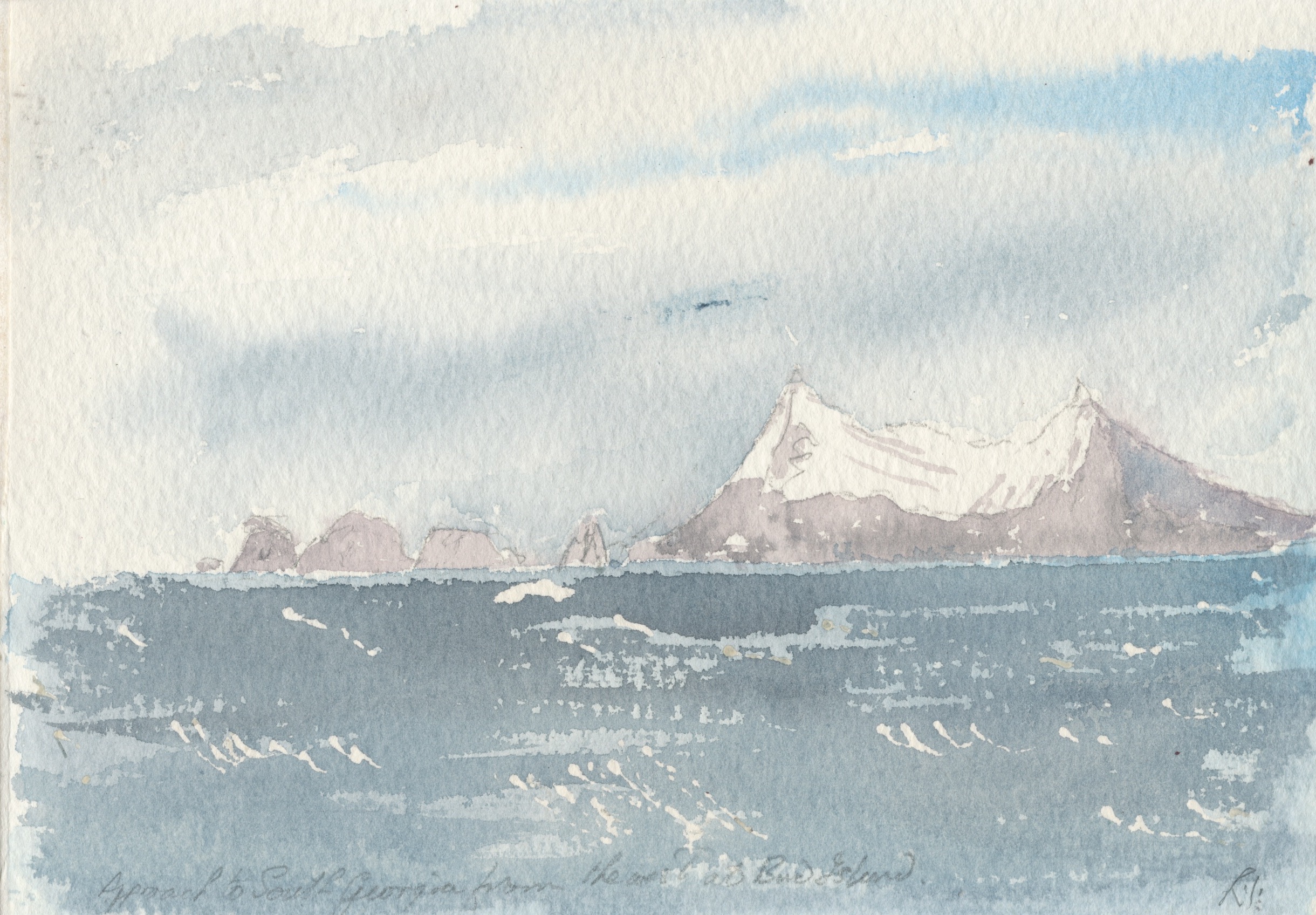

Early in January 1964 the MV Kista Dan, chartered by BAS for the voyage south came into the harbour. I tumbled aboard and found a berth amidships. We headed to the east towards South Georgia. The island, with its towering snow-clad peaks also holds memories. In 1916, after sailing in an open boat from Elephant Island, 800 miles south-west, explorer, Ernest Shackleton crossed these very mountains in a quest for his and his crew’s survival. This followed months living on the ice after his ship, Endurance, was gripped, crushed and sunk by the ice of the Weddell Sea.

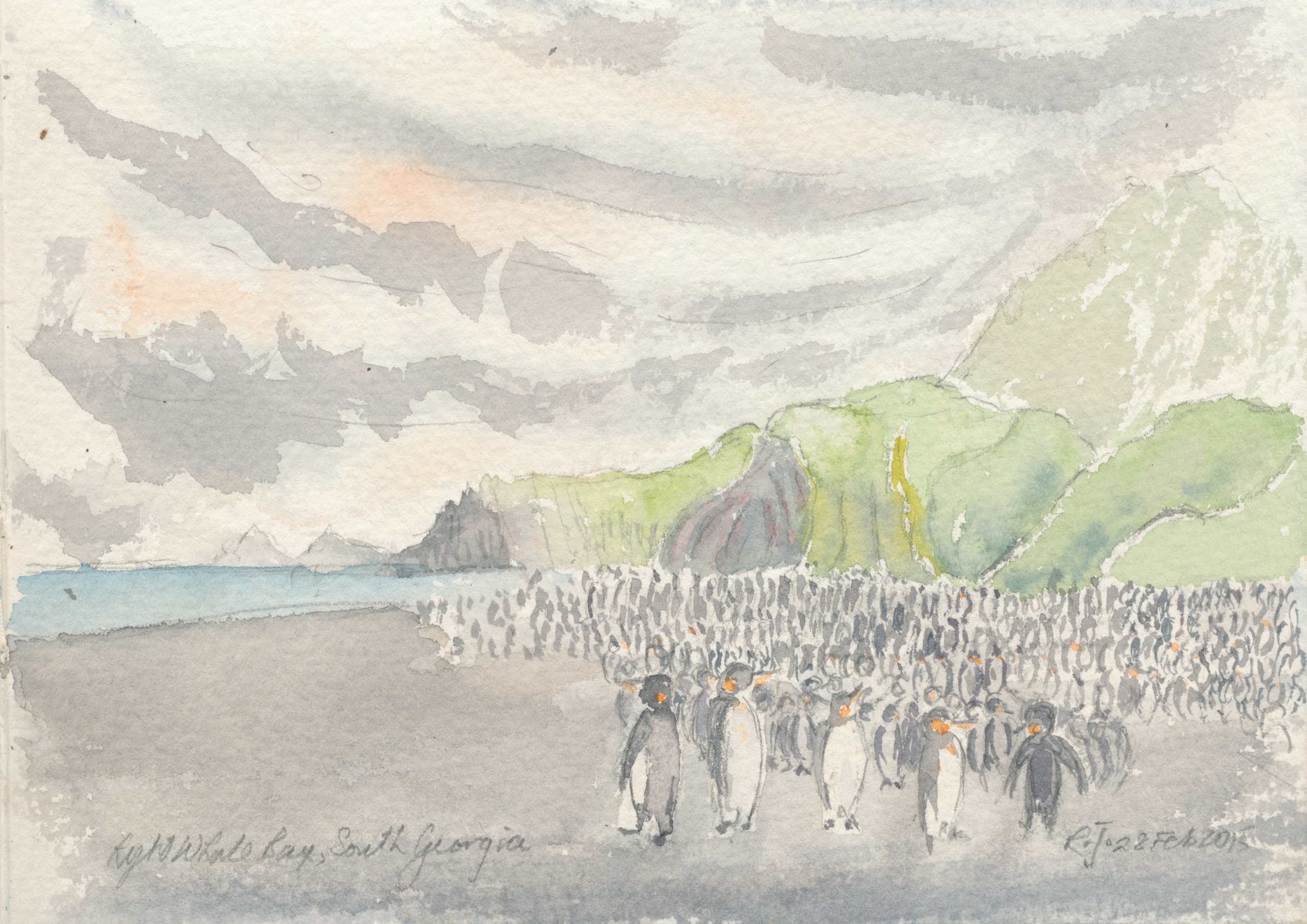

St Andrew’s Bay, South Georgia is home to a now recovering population of 200,000 pairs of king penguins their guano staining the seawater pool pink.

Shackleton is buried here having died of a heart attack on a later expedition. “Let him be buried where he fell,” his widow said. Shackleton’s grave has become a place of pilgrimage. A few years ago, his second in command, Frank Wild, was brought from an obscure cemetery in South Africa and reburied beside Shackleton’s tomb. When I visited the island in 2015, we gathered round their graves and drank a tot of whisky, raising our glasses, “to the Boss.” Somehow South Georgia has become Shackleton’s Island now. A landmark of a human feat in the face of an indifferent nature.

Horseshoe Island provides a sheltered landing for visitors to the base hut from where, in 1958, Stanley Black, David Statham and Geoffrey Stride set out for the Dion Islands and were lost on sea ice.

But back in 1964 at some point during the two-day voyage, we crossed the Antarctic convergence, where the warmer Atlantic waters meet the ice-cold Antarctic currents. Entering this zone, re-categorised only in June 2021 as the fifth ocean, is, in many ways, as significant as a landing on the continent itself. The border is almost invisible but the colour of the water alters and the waves change shape. The air is colder and damper and clutches at the throat – the body senses that you have crossed into Antarctic territory. Birds crowd the air and whales exhale their misty breath. Lost perhaps in a sudden grey storm of sleet and whitening snow is a first sighting of an iceberg, harbinger of the highest, coldest, windiest, driest continent on earth.

Sea ice prevents us from visiting the historic British base at Hope Bay (now Esperanza) where Oliver Bird and Michael C. Green were lost in a catastrophic hut fire in 1948.

Antarctica. It could not be more remote and strange if it were on another planet. Antarctica is a place of deep spiritual resonance. The landscape penetrates and imprints itself not only on all five senses but also a sixth, the imagination. Its sights, sounds, smell, touch and tastes are unique; so is its hold on the mind. As you watch, the light changes constantly glowing or darkening. The clouds shift, throwing shadows of themselves, the water scatters the light this way and that.

My memory of this place is multisensory: the susurrance of snow snickering and sneaking across the surface of the ice. The clatter of splintering ice falling from cliffs onto the sea below and the soft bellow of breath from a breaching whale. The wail of the wind, the clatter of a tent’s incessant, insistent flapping, the call of a dog driver urging his team on and the howl of huskies serenading the moon – sounds not heard elsewhere on earth in such profusion. The sense of smell is cauterised by the deep cold but enlivened by penguin rockeries and seal haunts which smell of guano and dung. Penetrating frost affects the whole body, the nose is first to whiten under frostnip followed by the cheeks, the ears unless enmeshed and covered. Fingers in gloves and mittens several layers deep feel the iron cold too, hardly checked by leather and wool.

The year of the quiet sun

Halley Bay research station is far south, deep in the huge gulf of the Weddell Sea – an area as big as France. The station was built in 1957 on shelf ice that is locked to the seabed hundreds of feet below but is slowly pushed out to sea by the ice cascading in frozen motion down from the continent’s heart.

When we arrived in January 1965, the station accommodation and working spaces had all sunk below the scurrying snow. On the surface, there is a dismal and desolate landscape: the interminable white interrupted by grey steel communication and observation masts. The sun was our only companion, providing light; yet, at the same time, it signalled the coming winter, dropping lower as each day got shorter and each night got longer. Finally, it only peaked above the horizon for a few moments before disappearing for a hundred days, leaving us in perpetual night.

Thousands of king penguins crowd the beach at Right Whale Bay in a checkerboard life amongst the dead whale bones.

In the dark winter, an emperor penguin colony establishes itself on the sea ice in a bay close to the base. The area becomes alive with their prehistoric, searing calls as they waddle eggs across their feet in rotating flocks for warmth. They are oblivious to man, who is perhaps regarded as a rather larger, mostly friendly, penguin.

Two towering basalt buttresses guard the northern entrance to the Lemaire Channel named Una’s Peaks for a former secretary to the Governor of the Falkland Islands.

1965 was dubbed ‘the year of the quiet sun’, seven years after the International Geophysical Year, when solar activities peaked and the world’s scientists were mobilised to study and record the changes in the ionosphere and other geophysical characteristics. There were 32 men on base: physicists, meteorologists, surveyors, geologists with support staff, diesel mechanics, tractor mechanics, cooks, radio operators, radar men, carpenters and a general assistant or two with previous Antarctic experience to keep the wheels of the base running smoothly. Everyone had their allotted job but surveyors and geologists waited anxiously for the spring, since their work is in the mountains, far away from base.

We spent winter in huts deep below the surface, overhauling dog sledges, counting stores, clearing passages and ladders of ice. The hours pass slowly despite the metronomic regime of work and meals. The day is broken into four two-hour work periods interspersed by an hour for lunch and two tea breaks of half-an-hour, morning and afternoon, called ‘smoke-o’ when men come in from their offices and cubby holes or the meteorologists from balloon tracking and the black gang from working on the generators. In the early part of our year on ice, we were working outside in temperatures and wind speeds that made the smoke-o break the more welcome. All was banter, cynicism and laughter.

The Lemaire Channel opens up, a chasm between precipitous cliffs dwarfing MV Plancius threading her way south.

Very occasionally we found time to drive our dogs out to the edge of the shelf ice to where the frozen sea-ice stretched endlessly to the horizon. Two years before we arrived, Neville Mann had been lost with a team of dogs as the sea-ice was swept away from the shelf ice. The thoughts of this lonely, icy death chilled our hearts. But we awaited the return of the sun with psychic passion until, after a hundred days, it peeps above the horizon as if frightened, disappearing in moments leaving a welcome bloody stain in the northern sky. Soon, soon we will be sledging to the far unexplored mountains.

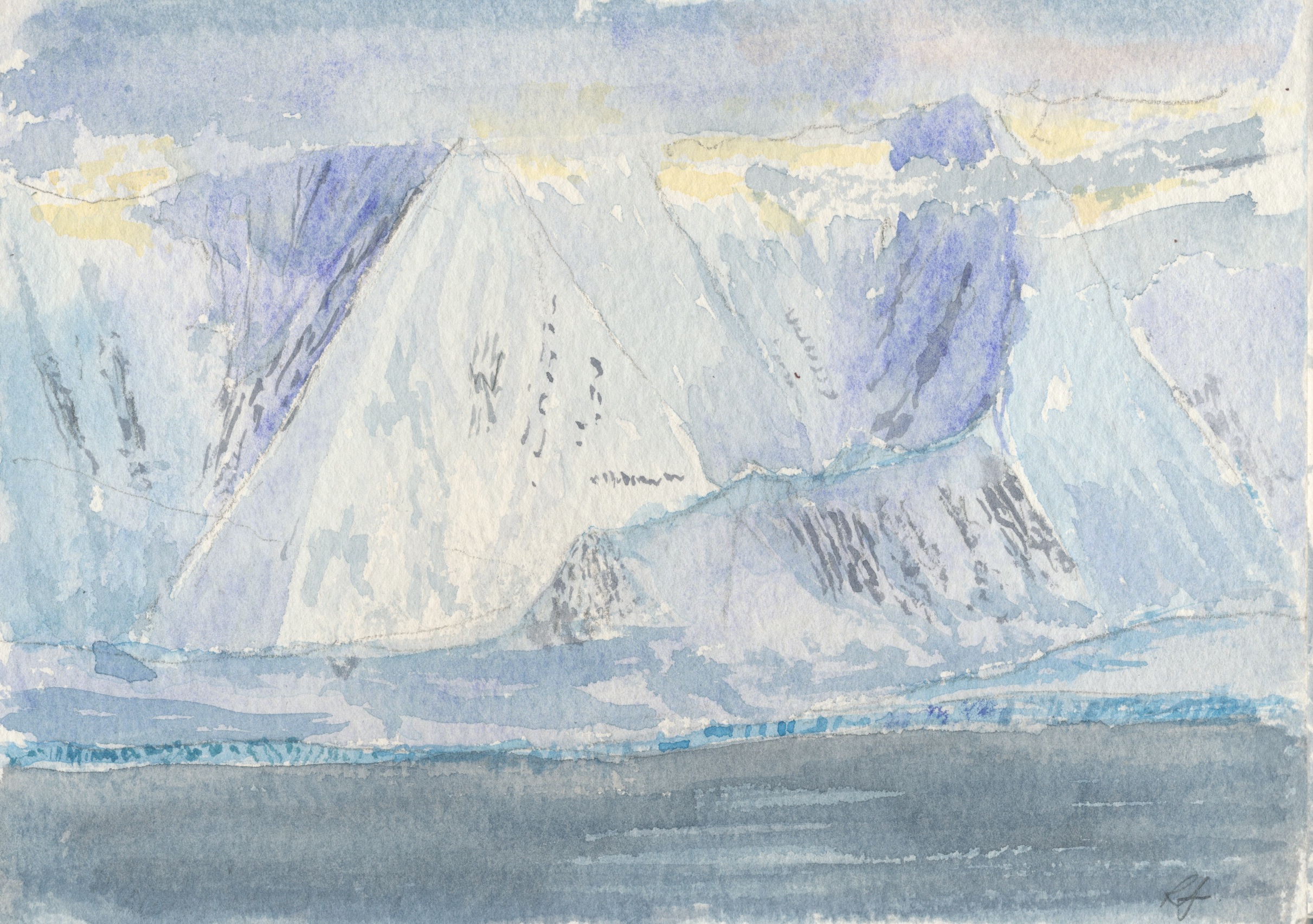

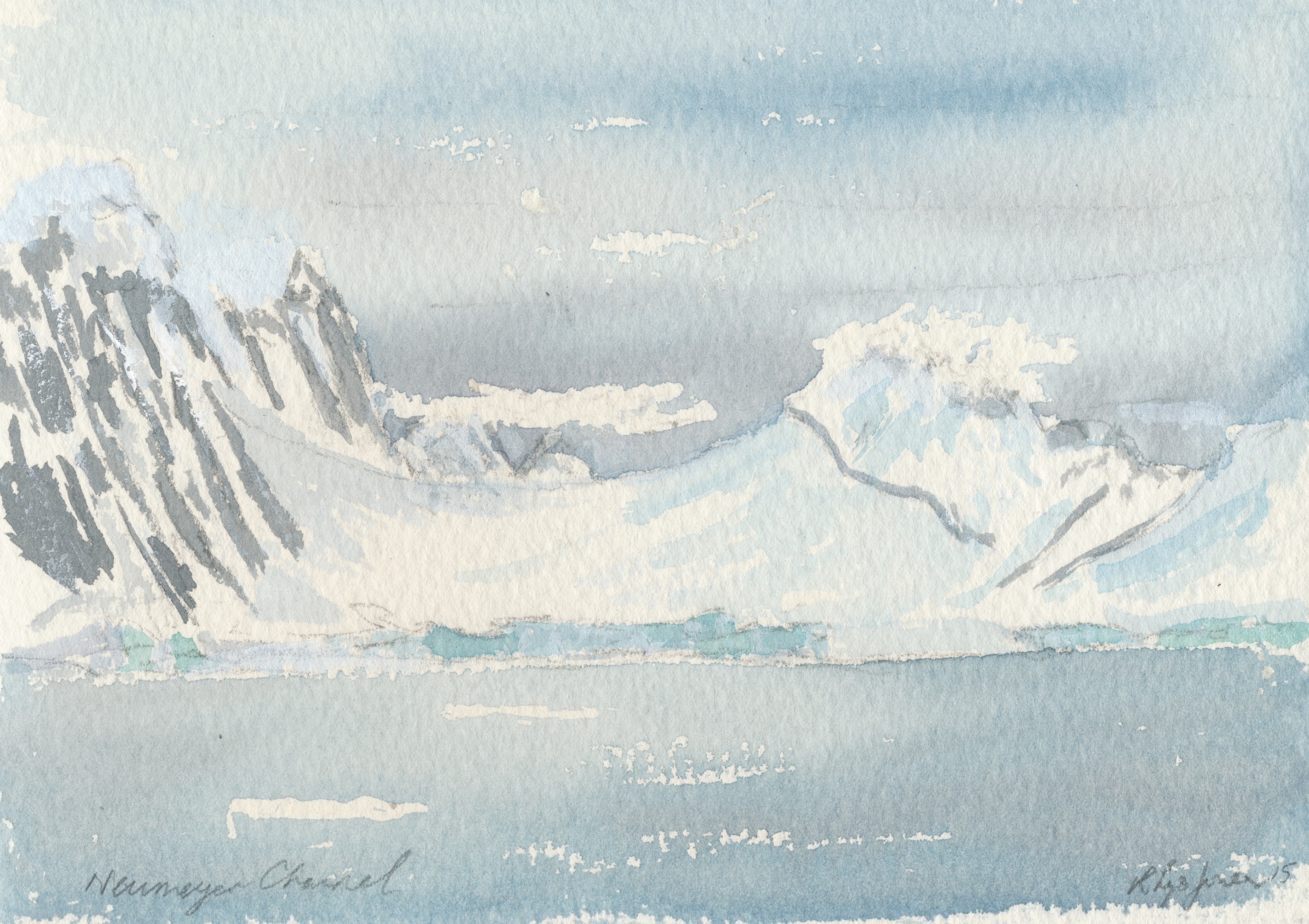

Low sunlight creeps under the clouds that hang over the mountains in the Neumeyer Channel throwing deep shadows of indigo and violet.

The Antarctic Monument

In 2002 I attended the annual meeting of the British Antarctic Survey Club held in Edinburgh. It was the first meeting of veterans I had attended since I left Antarctica 38 years before. After so many years, I had perhaps come to terms with the feelings of anger at the disorganisation and chaos that had led to the death of three of my companions in a crevasse accident – an anger that seeped out whenever I had drunk a wine glass too much and was amongst friends.

As I sat in the meeting, I was drawn back into a memory of a spectacular day in the mountains. I had found beautiful fossils of glossopteris leaves from when Antarctica had been covered in forests of fern-like trees. The geologist I was with, Lewis Juckes, believed we would find fossil beds that would show that this part of Antarctica had been interconnected to Southern Africa in the very remote past, as part of the supercontinent Gondwanaland that also included Australia and India. The finding contributed to the jigsaw of theory of continental drift – no place stays in one place through geological time. I had made a small contribution to discovering this world.

Deceptively smooth snow saddle under a fluff of white clouds in the Neumeyer Channel.

But another scene resurfaced of that spectacular day. That evening I had been lying on my back peddling the generator to provide power to the radio and listening to the crackle and pop of static. There were regular radio schedules with base every couple of days and we could hear PandO, the radio operator at Halley Bay and morse being tapped out. We started to check the letters and, as we did so, PandO cut in, “Do you know what you are sending?”. The Morse continued: dit dit dit da da da dit dit dit and again the same signal, dit dit dit da da da dit dit dit. It was the international distress signal I had read of in fiction, being broadcast for real: an SOS call from our colleagues several hundred miles away through the mountains.

The story dribbled out with PandO translating each line of morse into speech. A tractor had fallen into a crevasse killing three men, Jeremy Bailey, John Wilson and Dai Wild. Travelling late in the evening, they had not picked up the tell-tale sign of a crevasse: a ripple in the surface texture, a slightly deeper blue tone in a line across the path of the tractor. One man, Ian Ross, survived the catastrophe. He had been travelling on the back of one of the sledges overseeing the husky team tied on to a towing cable.

Approaching the Willis Islands and Bird Island on the eastern tip of South Georgia in our voyage from the Falkland Islands.

After some hours he realised his efforts to lower himself into the crevasse would not help any of his dead companions and would seriously endanger himself. Unable to drive dogs, he had led them on foot back to Pyramid Rocks – the main exploration camp in Tottanfjella – where two mechanics were mending broken tractor drive shafts. There, the fateful SOS was sent.

It took Juckes and me three days to get back to Pyramid Rocks and a further three days to reach the scene of the accident. Twelve days after, it was as bleak and lonely a place as ever claimed young lives. We rescued the sledges from the lip of the crevasse with their load of food and fuel. I made a cross from a spare slat of wood for mending sledges. We said a prayer over them, squashed below us in the cab of the tractor. There they will lie until the very last trump on their catafalque of ice.

I was jerked awake, back in Edinburgh, the chairman was reading out some of the names of the dead. I was shocked by their number. Only a few hundred had wintered in Antarctica and 28 Britons had died in the forty years between the first permanent Antarctic base being set up in 1944 at Port Lockroy and 1984. One since: in 2003 Kirsty Brown was attacked by a leopard seal when carrying out research beneath the ice.

I offered to help raise funds. By chance, I met the sculptor Oliver Barratt who had designed a memorial for those killed on Everest – a memorial that is updated each year as the ambition to climb is overcome by weakness and weather. Oliver conceived of an Antarctic monument that is in two parts, the northern part made of two pillars of British oak to be sited in the UK and the other part, a stainless-steel needle made to the shape of the empty space between the two oak pillars to be positioned somewhere in the south. It was symbolic of the separation of the families and the time and space between them, the fortitude, the loss.

Strange lacey black clouds throw a cover across mountain peaks in the Errerra Channel.

I was joined by two Fids: Julian Paren and Dick Harbour. Fids are those veterans who had worked in Antarctica for the Falkland Island Dependencies Survey or its successor, the British Antarctic Survey. Sometime later we were joined by Brian Dorsett-Bailey who had lost his brother Jeremy, the colleague who was one of the three that lost their lives on the 1965 expedition. Together, we set up a charity, the British Antarctic Monument Trust, to commemorate those who had died in British Antarctic Territory ‘in pursuit of science’.

We arranged for the northern monument to be sited outside the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge University itself a memorial to the memory of Captain Scott and his companions. It was unveiled 12 May 2011, a couple of days after we had dedicated the Antarctic memorial in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London. Shortly afterwards we decided that Stanley in the Falkland Islands would provide a suitable site for the southern monument. It was the gateway to the Antarctic through which all British explorers travelled on their way south in those days. We set about the daunting task of raising the money.

Memorials on the ice

In March 2015 some two hundred people were sheltering from the incessant wind on the waterfront at Stanley, Falkland Islands, beside the Antarctic monument cloaked in rippling crimson fabric. There was an audible gasp as it was pulled away revealing the shining needle. I spoke about the need for the recognition of the sacrifice of these explorers. The Bishop of the South Atlantic said a prayer of dedication and the Governor of the Falklands spoke about the importance of the links between the islands and Antarctic exploration. Rupert Summerson, who had lost companions years before, played a moving lament on a Japanese Shakuhachi before we all retired to the Museum for welcome refreshments. We sailed south that night.

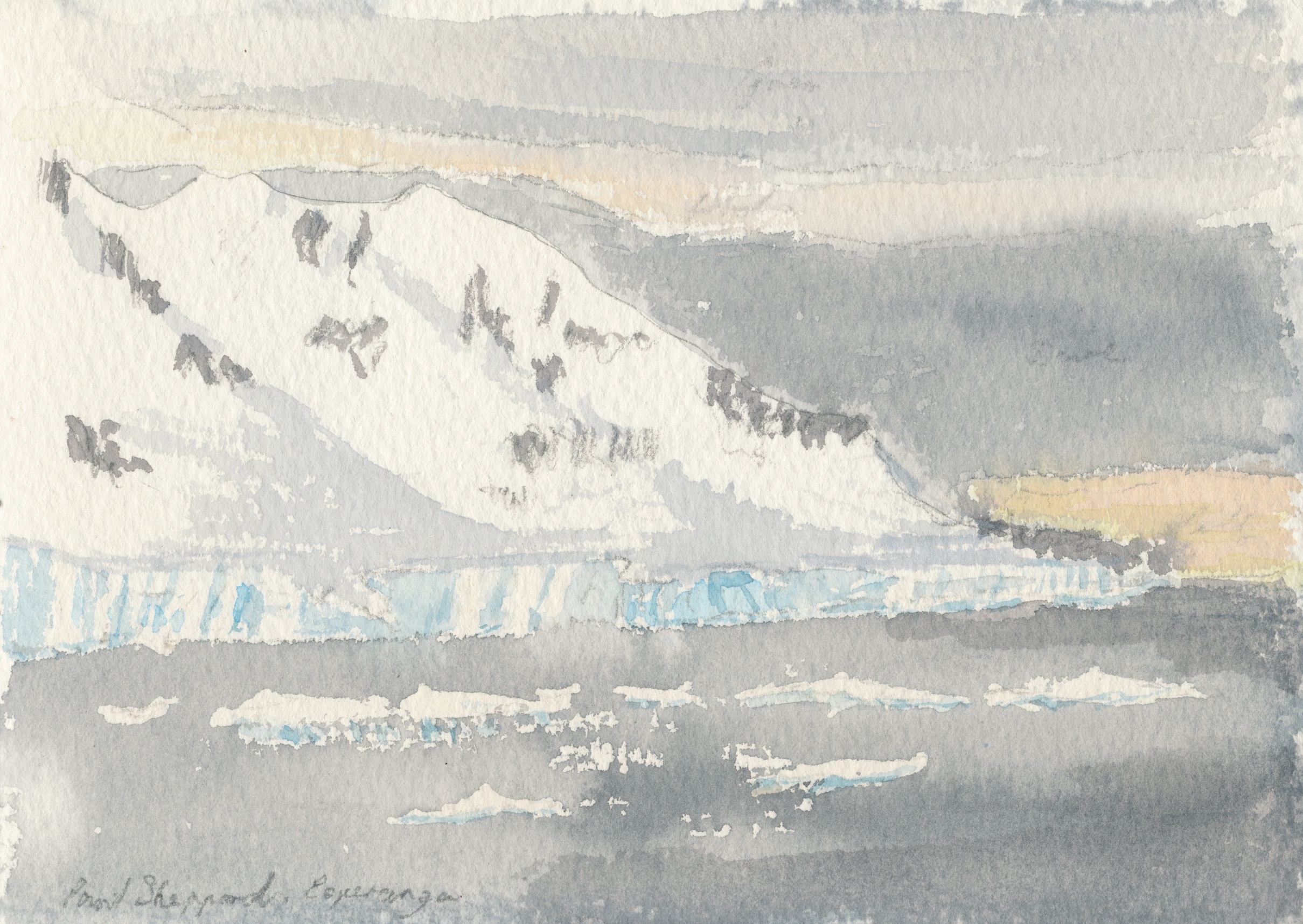

Point Sheppard at the entrance to Hope Bay was named for the Captain of the charter ship Eagle that established a British base there in 1945 – the first permanent base on the mainland of the continent.

The itinerary of our three-week voyage aboard MV Ushuaia included many stops: at Signy Island, Hope Bay, Argentine Islands, Faraday station, Horseshoe Island, Rothera Bay, Marguerite Bay, Stonington Island, Paradise Bay and Deception Island. Each place safeguarded a fatal story of young lives lost in the pursuit of science. Drifting sea-ice or bad weather sometimes prevented us from docking, yet, as best we could, we visited those sites and paid homage to the lives they had claimed.

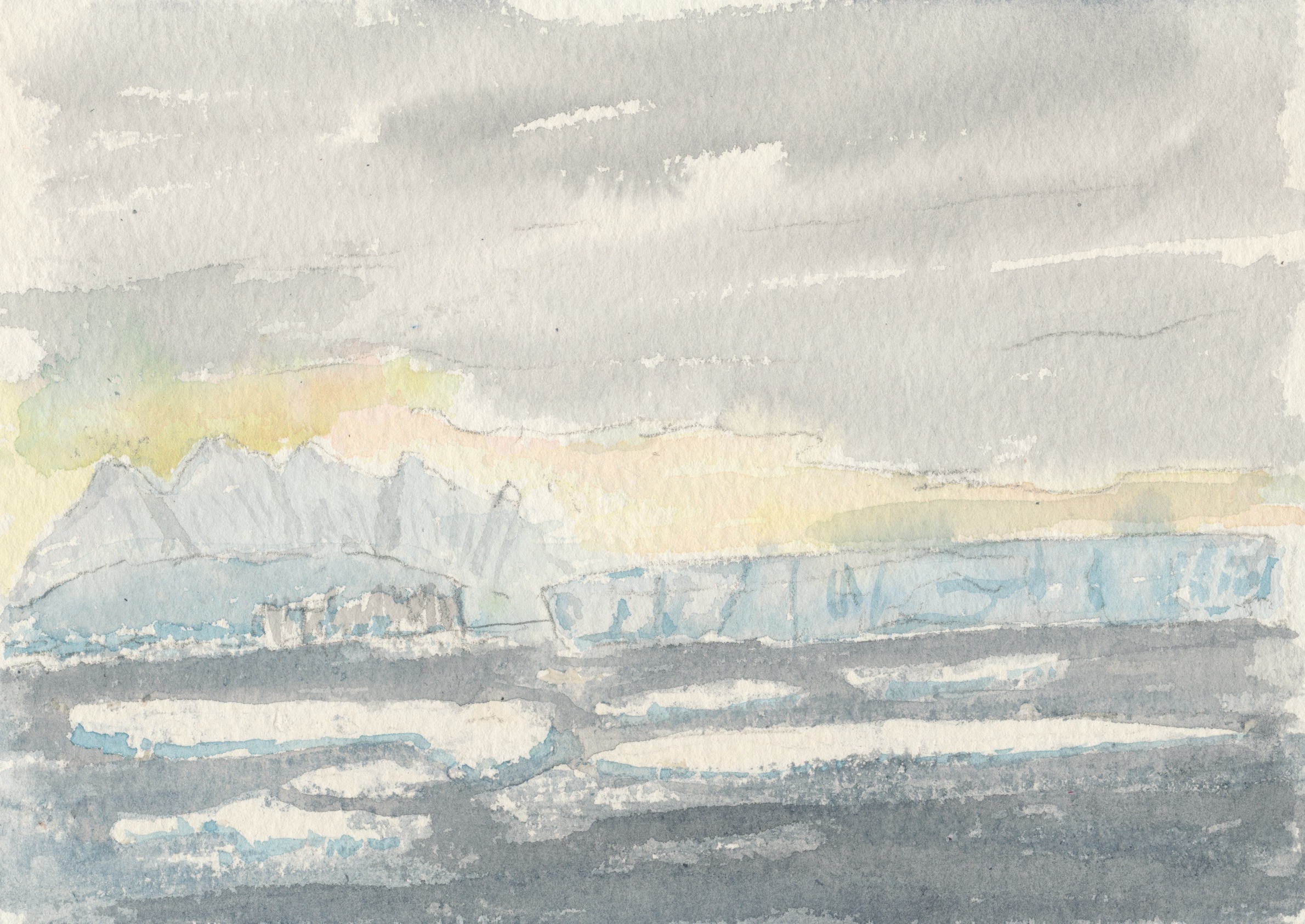

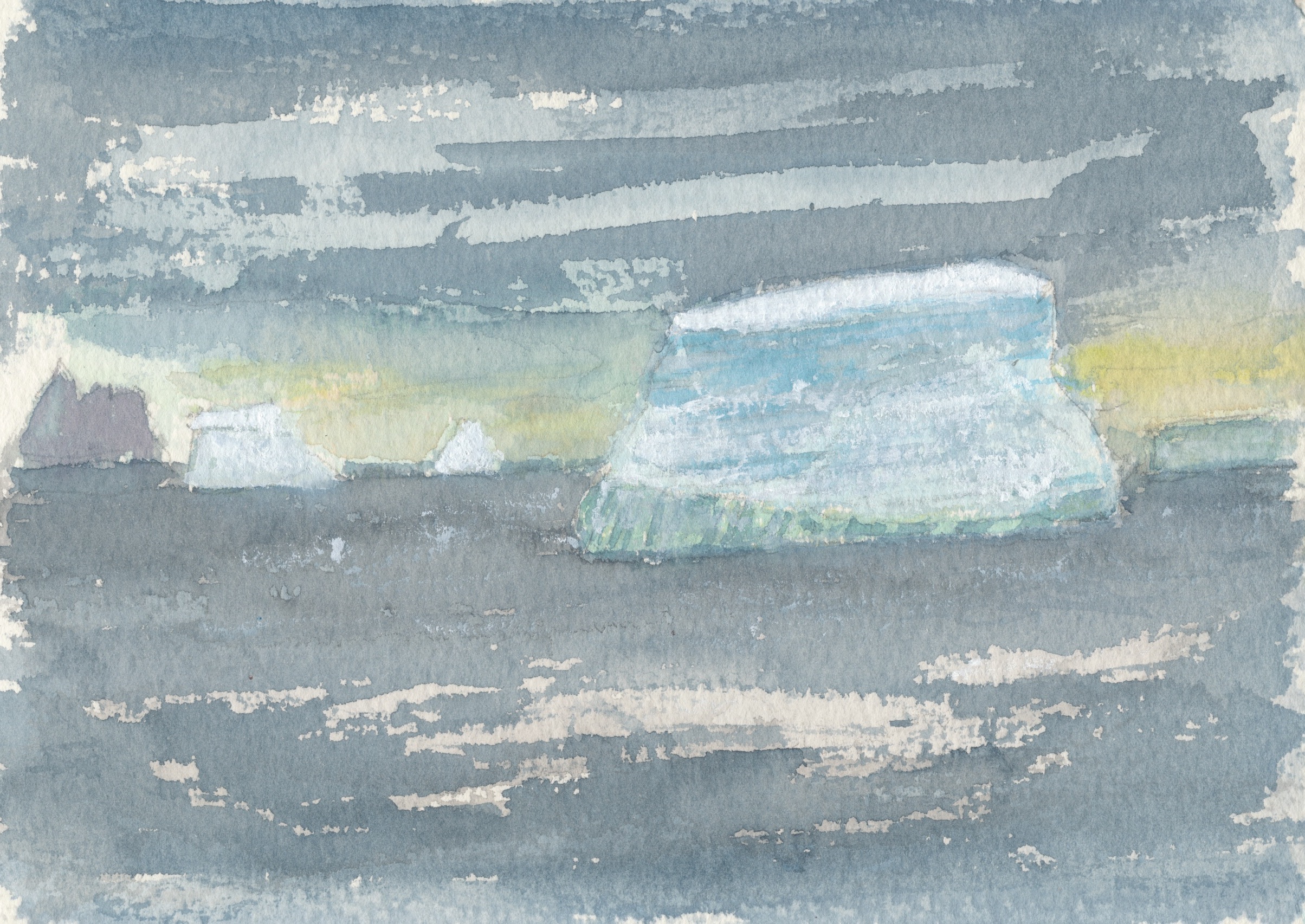

Icebergs of all colours blue scour the slate grey seas around South Georgia.

Bad weather prevented us too from visiting our final stop: King George Island, now the Brazilian research station, Commandate Ferraz. Here, crosses mark the loss of four Fids at Admiralty Bay: Eric Platt who suffered a heart attack in 1948, Ronald Napier who was drowned in 1956, Alan Sharman who slipped and fell down a snow slope and Dennis ‘Tink’ Bell who died in a crevasse in 1959. At noon everyone gathered in the saloon of the boat to hear about them.

David Bell spoke movingly of his big brother ‘Tink’ who died a few days after his 25th birthday in July 1959. “He was a very funny chap, good company, clever,” David said, “This trip makes a final closure for me and perhaps for many others.” Fergus O’Gorman who came south with ‘Tink’ and Alan Sharman on the RRS Shackleton in 1957 said, “it seems a long time ago and yet it is very fresh in my memory.”

He went on, “surviving anywhere is difficult. In the Antarctic it is particularly difficult. Alan was out walking with one other Fid and a husky and they went over a ten-foot ice cliff and Alan hit his head on a rock and died… Only a little more than a month later Tink died at Admiralty Bay…” Fergus’ voice had fallen to a whisper and there was utter silence in the saloon.

Alan Cheshire, who had worked in Antartica for several seasons and lost colleagues, walked forward and without preamble read a poem he had written during the voyage:

“All Fids leave part of themselves in the Antarctic when it’s time to go home.

So in a very real sense, the souls of those who rest here for eternity are never, ever truly alone.

They are an integral part of who we are today.

And whilst we may grow old and memories fade, they remain forever young, and forever in our hearts.”

Members of the 1965 expedition to the Tottanfjella – the author is on the far left.

Notes

The text is illustrated with watercolour sketches that the author painted on site whilst revisiting the Antarctic in 2015 on a voyage along the Antarctic Peninsula he organised to remember “those who lost their lives in Antarctica in pursuit of science to benefit us all.” The breathtaking changing scenery of ice, snow, rock, sky clouds and shadows was an inspirational change from the flat monotony of the shelf ice of his earlier visit fifty years earlier.

All images by Rod Rhys Jones

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »