Digital shadows

The seabed of the Venetian lagoon teems with thousands of bygone objects. The search for the legendary third column of St. Mark, which is thought to lie in these murky depths, is an opportunity to return their shadows to the surface.

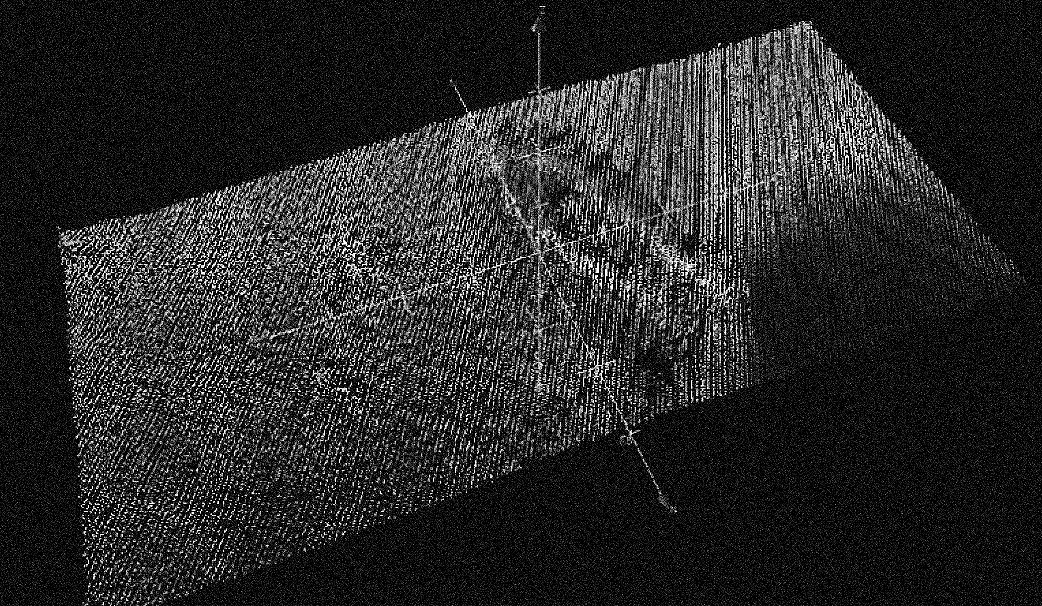

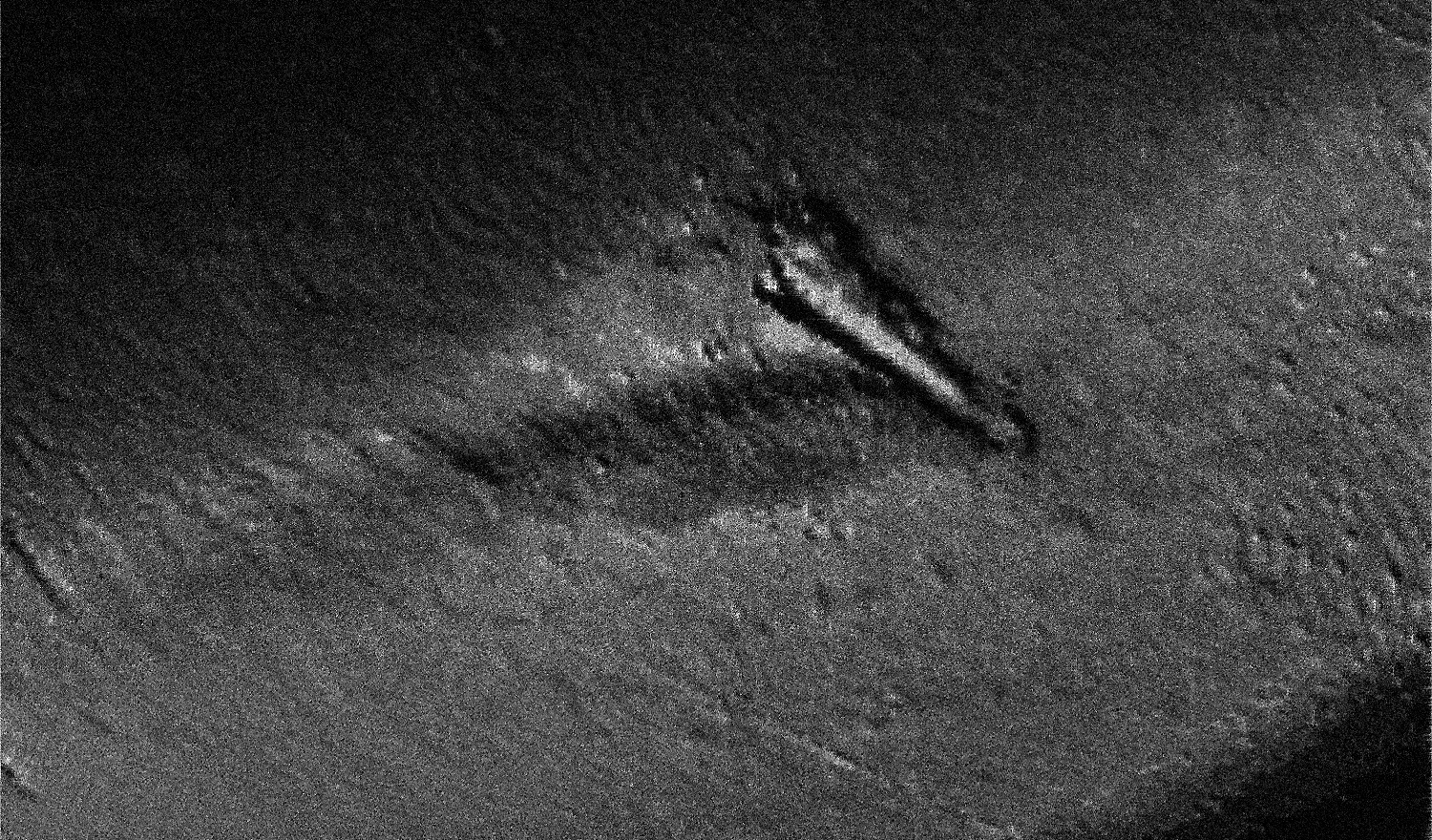

Our equipment normally serves other purposes. By insonifying the seabed of the lagoon, thus giving names to the multitude of forms that populate an otherwise indefinite depth, we aim to bring to the surface its origins, the geological structure and archaeological mysteries of this ancient breathing mass. As the multibeam echosounder proceeds, unexpected images are carved out from the terrain, blazing on screen after having remained dormant for years. These are the digital shadows of any sort of wreckage and rubbish, silently coexisting with the abundant subaquatic life, protected by the dark membrane of the Venetian muddy waters.

It is by looking at this rich submerged archive that we came to the decision to try and use the technology to search for the third column of St. Mark. Certainly, we are not the first to undertake this endeavour. Centuries ago already, as humanist writer Francesco Sansovino tells us, a “good man” volunteered to locate the absent monument by exploring the waters next to Ponte della Paglia.1

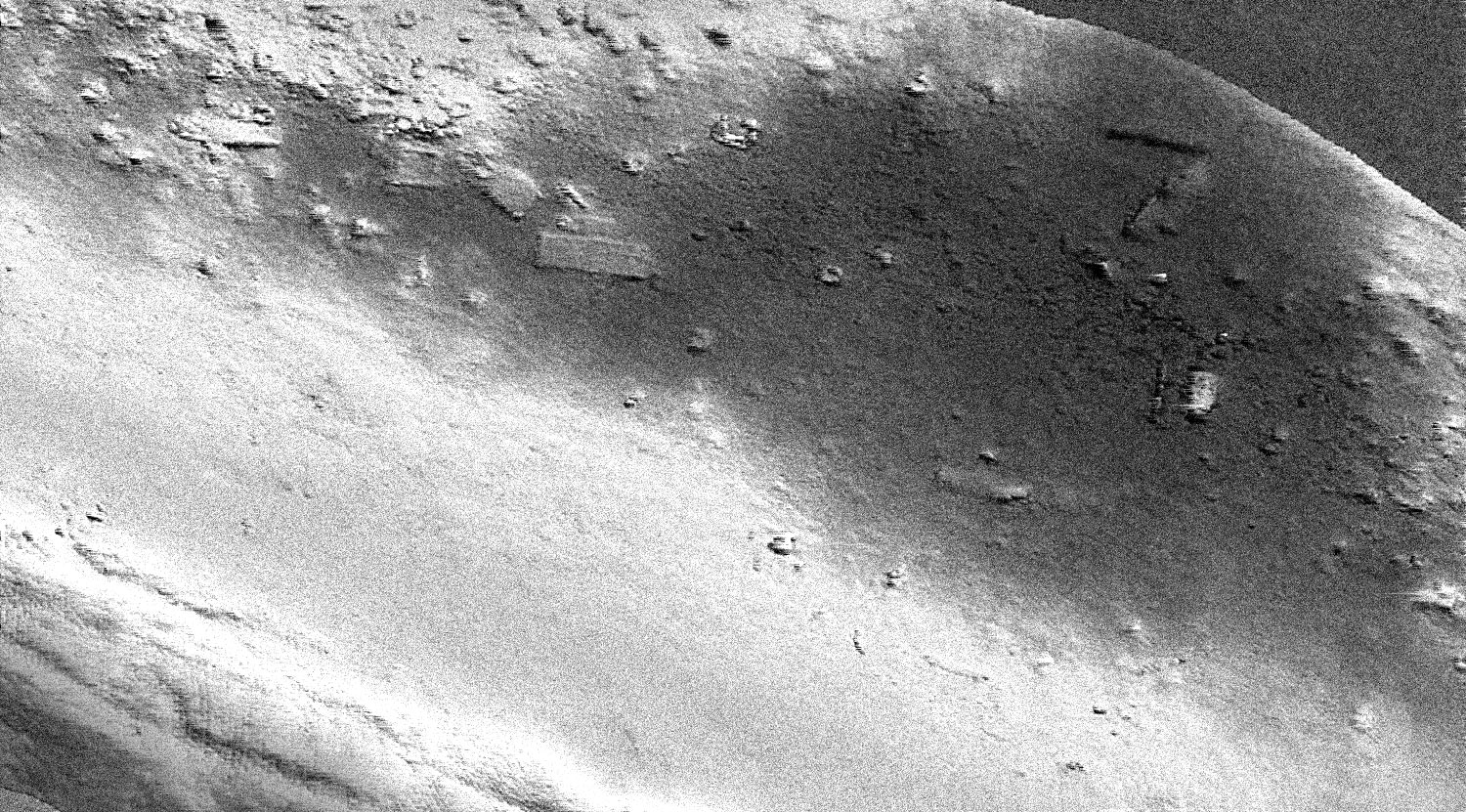

Who knows if this man, who could only fathom the obscure depths with the use of a long iron bar, had to himself face a similar plethora of unexpected hints. For the difficulty of our hunt lies precisely in this: not in that we are searching for something that may have disappeared forever, but rather, in the fact that we are uncovering too much. We have to deal with the city’s unavoidable tendency to conserve everything: once underneath, the lagoon is a vast chamber of things, constantly transformed by the sonar into a spectacle of visible echos and noises, the bulging score of an undefined symphony.

Above the surface, life proceeds as usual. In Piazza San Marco, multitudes of tourists gather to admire the ancient wonders of Venice. As one strolls through the crowd, it is difficult to imagine how a fundamental part of this landscape – the two majestic columns that dominate the Piazzetta overlooking the waterfront, next to the famous basilica – may be lacking its completing element. Yet, as the chronicles claim, three were the pilasters that captain Jacopo Orseolo Falier brought to Venice after the first crusade. It was a grand gift for the Doge of the Republic, brought by a fleet coming back from Costantinoples. The Lord of Venice, however, could not enjoy the offering in its entire splendour: one of the columns, the one creating the unnoticed void, was dropped in the sea during the landing operations.2

It is interesting how this absence has helped to define the physical and imaginative space of the cityscape since. For decades, the two columns represented the spatial frame within which many important events of the city’s life would unfold. Even today, the pillars have not ceased to give the impression of that grandiose entrance to the city that they once represented. Made out of granite, with bases of Istrian stone, the structures are topped by two fundamental figures that are part of Venetian identity. The one on the right (as seen from the island of San Giorgio) hosts St. Mark in the form a winged lion. As Sansovino remarks, the fact that the lion looks towards the Levant may indicate the powerful influence that Venice held over vast areas of the East.3

On the other column is a sculpted image of St. Theodore, the first protector of the Republic. Holding a shield in his right hand (the hand “normally meant to offend”), the statue may have epitomised the politics of a city willing to resort to war only when it needed to defend itself.4

In the shade of the columns, the convicted were sent to justice,5 making this space an area charged with such meaning that, still today, some locals prefer not to walk between them. Not by chance, the Venetian saying “To be between Mark and Theodore” describes the state of being in a situation that is very difficult to resolve. The space between the columns was also the only area of the city where gambling was allowed: the privilege was granted to Nicolò Barattiero (literally “the blackleg”) – the Lumbard engineer who first succeeded in raising the pilasters after years of laying on the bank.6 We do not know with precision where the third column was originally supposed to be placed. Should its positioning be in line with the other two, the idea of a city gate would probably feel contradictory, and the space between the columns might have become the backdrop for other types of events. Of course, it is impossible to say.

But rather than trying to grasp the imaginative prerogatives of the missing relic, it is in the search for it that we may today find its fundamental symbolic reach. Looking for the column has indeed an important resonance. In the recent years, the public has demonstrated a growing interest in our project, with interviews, press releases and documentaries warmly accompanying the search. This is far from being a trivial curiosity. In fact, the search for the relic suggests the existence of a different city. It reveals a tradition of studies and scholars whose contribution fights the risk of Venice fossilising into a beautiful and untouchable crystal. In unraveling the secrets of the seabed, we hope that projects like ours can bear witness to a different type of city-shaping, that goes beyond the prevalent touristic dynamics. The type of data that we gather, opens up another dimension, allowing novel views and stories to reach the surface.

Just look at the maps yourself: hundreds of objects, where car tyres and entire boats are the only things that are most recognisable. In the depths of the lagoon, these objects settle for centuries, if not for millennia. When facing a city that is losing its inhabitants, as whistle-stop visitors take their place, the images that we unexpectedly find are the opportunity to establish a geography of continuity, to compose a biological growth of the city that feeds of its own debris, contradicting the frozen fruition that is happening on the ground.

As for the column, the search continues. We have recently started to use even more sophisticated instrumentation, penetrating the muddy terrain. Of course, this is not enough yet, and we need to decode what the image is trying to tell us. Objects have become stratified: shapes have merged into each other, their nature has become one with the ground. So, whilst at first there is remote sensing, in which the image is seen and interpreted on screen, then afterwards, someone has to go down there, verifying in person the truthfulness of the digital image. This is the language that is spoken by an unexpected world, in which the legend becomes one with the leftovers of daily life. What will be found down there? Whilst above the surface everything proceeds as normal, the lagoon swallows the centuries, patiently collecting the flow of its own life.

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »