Beneath the Mead

In the 17th century, an underground cave was discovered in the depths of the Bristol area. Today, the entrance to the cave, Pen Park Hole, lies adjacent to a housing estate in the northern suburb, Southmead. The site above had plans for residential housing but permission was denied when the hole became a Site of Special Scientific Interest in 2016. The video work, Beneath The Mead: cigar.lend.shave (2020) by Artist Laura Phillips, commissioned by Spike Island, Bristol, channels the curiosity that locals express towards this obscure part of their landscape. In this text, the artist reflects on the making of this work and the relations at play in these narratives of what is known and unknown about the place one calls home.

My film is a speculative portrait of a place in North Bristol called Pen Park Hole. As the name suggests, this place is formed by a void in the landscape. In fact, Pen Park Hole is a 190 million year-old cave that spans 70 meters wide and 60 metres deep. For many years, it was the deepest known cave in Britain.

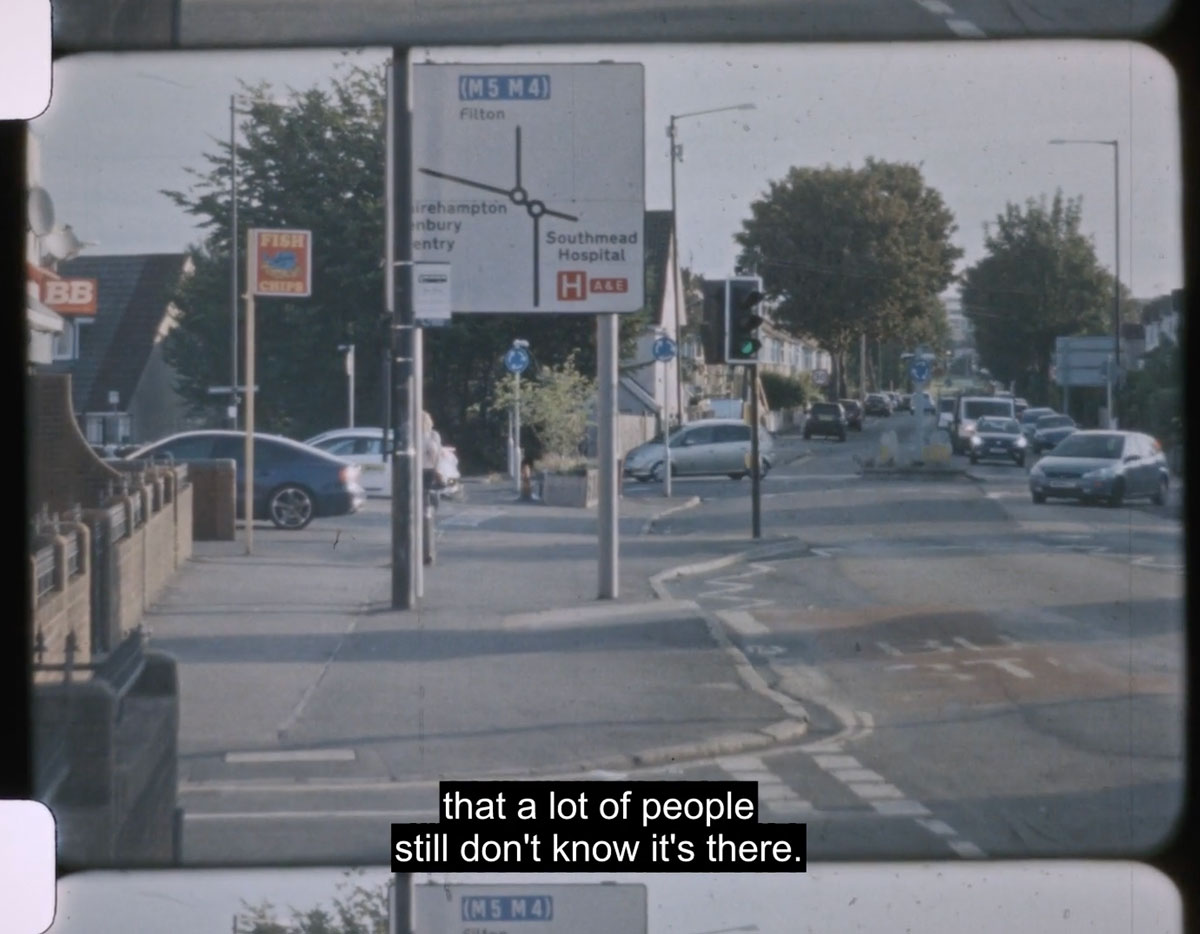

The entrance to the cave is adjacent to a housing estate. The site was subject to planning permission for residential homes, but this was thwarted in August 2016 when the geological origins of the cave, as well as its invertebrate community (including the cave shrimp Niphargus) led to its designation as a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

It was the evening of 22nd June 2016, when my interest in Pen Park Hole and Southmead began.

During this time, I had moved back to my parents’ house in Southmead, a northern suburb of Bristol, the South West of England. It’s a place I know very well, a childhood home, with most of my family not living very far outside of the BS10 postcode. Since moving away, the horizon line has changed significantly, especially with the construction of large hospital buildings of the North Bristol NHS Trust.

In the morning I awoke to the news, ‘Britain to leave Europe’, initially disappointed but not surprised. The area in which I was living had voted by a slight majority to leave. These voters, aka ‘Leavers’, include some of my closest family members. Yet, to many of my middle-class peers and colleagues at the University in Bristol it was a big surprise. To them, to vote ‘Leave’ was a marker of the far-right anti-immigration rhetoric of parties such as the UK Independence Party. For me it signified I had moved into a new zone within an increasingly divided Britain.

Dwellings

The Southmead housing estate next to the cave started as a large-scale development of the area in 1931, when the Bristol Corporation built 1,500 houses to the north of Southmead Road – partly to house families cleared from the rundown dwellings of central Bristol, partly to address the housing shortage at the time. A further 1,100 houses were built after the Second World War. Since the War, reference has often been made by the local community, to the ‘pre-war estate’ of Southmead and the ‘post-war estate’, with locals also referring to them as ‘the old estate’ and ‘the new estate’. It wasn’t until 2014 that the last of the prefab bungalows, originally intended as short-term solutions to the housing crisis after World War II, were removed from the estate. These buildings had a project life span of 10 years, but their use lasted a full 60 years.

Within the media there is a crass stereotype of the area, as most famously portrayed in the early 2000’s by the television show ‘Little Britain’ as a character called Vicky Pollard. Within local vernacular there is also a name for teenage residents’ – ‘Meaders’ – described by the urban dictionary as a person who:

Wears nothing but sports clothes such as Kappa, but only ever runs when nicking cheap cider. Also recognisable by their huge “gold” earrings. Past-times Meaders enjoy include: listening to rap groups with more members than brain cells (such as, So Solid Crew), drinking cheap cider nickin’ things, becoming pregnant at age 8, gelling their hair flat. A Bristol term that originates from the name of the Bristol area, Southmead.1

These derogatory terms pathologise the community so as to avoid addressing the complexity of social problems of the area, often involving intersectional and wider structural issues. It contributes to the trivialising of crime, violence and racism which happens in the area.

The book, Searching for Community: Representation, Power and Action on an Urban Estate by the late Jeremy Brent, charts the author’s thirty-year involvement as a youth worker in Southmead in the 90’s and presents a variety of perspectives to challenge the ways in which areas of poverty and disrepute are represented. It examines ways to understand and engage with the troublesome concept of ‘community’, vividly describing the collective actions of young people and adults to show the way community is enacted as a combination of dreams, actions and materiality.

Both Brent’s book and a feeling of alienation inspired me to think more about the area of Southmead and its community, providing the backdrop and the impetus to my film. In this way, Pen Park Hole epitomises the experience of a place that I know but don’t know.

The hole is the McGuffin in the story or the process of making this film. I have never managed to go down the hole, but it informs the talking point and structure to the film as a way to re-engage in the ‘local’ landscape, to hear voices from the neighbourhood and to expose these findings within the context of my own practice. To dig deeper into what constitutes a neighbourhood; its geology, community. And so I began with the neighbourhood on my very doorstep. I set about a closer inspection on the banality of a street in BS10 called Pen Park Road; a road I have travelled many times and on which the Hole is situated.

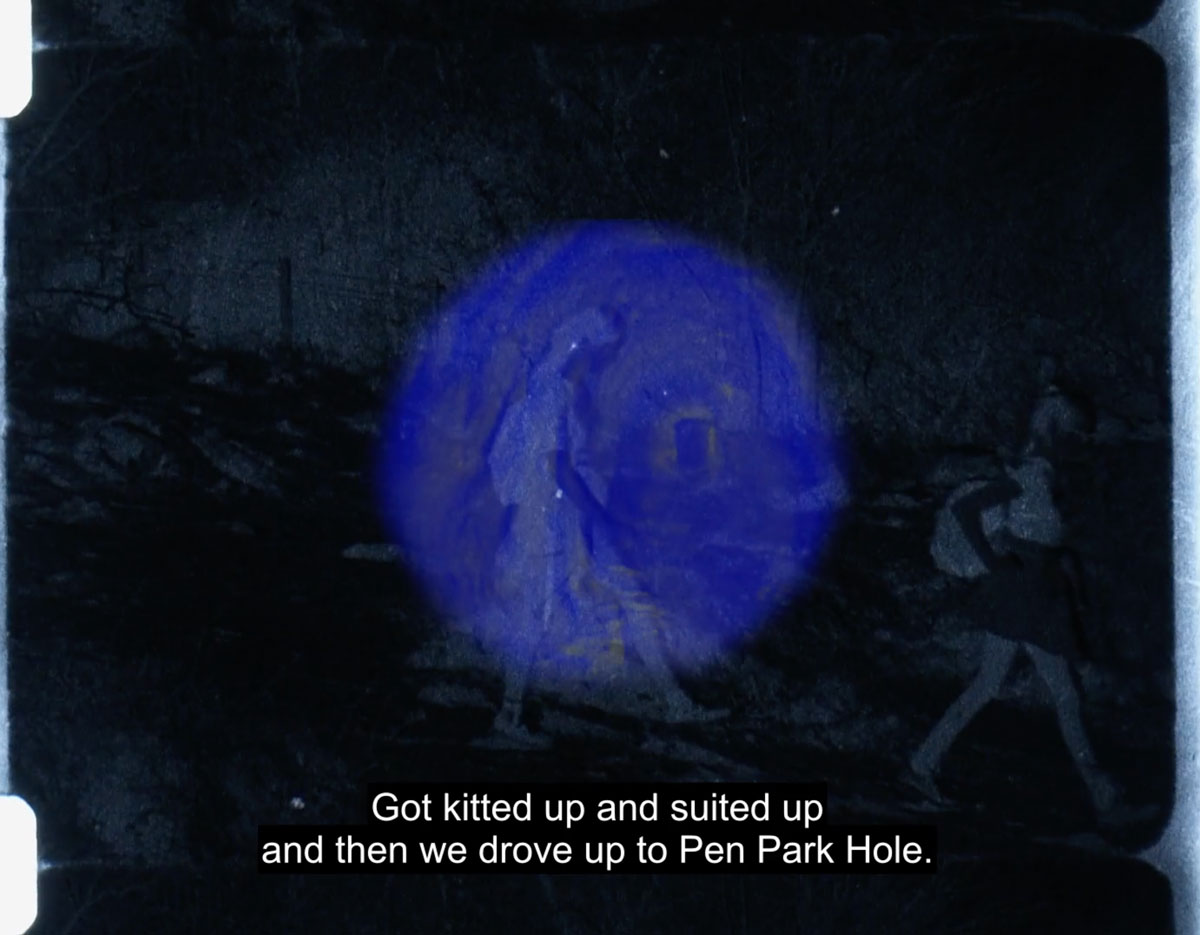

In late 2019, I carried out a series of interviews which had taken place at Southmead Library, and at a meeting with the Southmead Local History Group. The intention was to gather stories about the hole then collage it into a soundtrack as the beginning structure to the film; akin to cave exploration, sound and touch acts as the primary senses that navigate our path. Rather than address the sticky problem of representation of an area, I am more interested in the haptic memory and lucidity of time that experimental films can present. Like the lyric or poetic works of avant-garde filmmakers such as Chick Strand, Sandra Lahire or Margaret Tait; conversation drifts within a kaleidoscope of images, to conjure a fleeting sense of embodied experience. I often think great films are like those rare occasions where one has a deep meaning conversation with a stranger on a bus. Most interesting is the transmission of local knowledge about Pen Park Hole, and how these ideas are mediated within the community that lives on site – akin to an aural survey of what is commonly known or local folklore. What is understood is more important than the facts. In my encounters, I speak to only one woman who had explored the hole. The sound track is a snapshot of the current cultural memory and understanding of the place.

The imagery of the film was made just before and during lockdown: shrubs, fences, litter, trees, post boxes, signs, buses, dog walkers, vandalism, houses, cars. I film alone, as a process that invites conversation to those that travel into shot. As I am alone, and holding a curious object of a Ukraine 16mm Kiev camera, I am frequently stopped by people wanting to know what it is in my hands, what it is I am filming or sometimes just conversation about what used to be on site. In a naive way I hope to open up conversation and speculation, to question and wonder what lies beneath the Mead?

Ways of Seeing

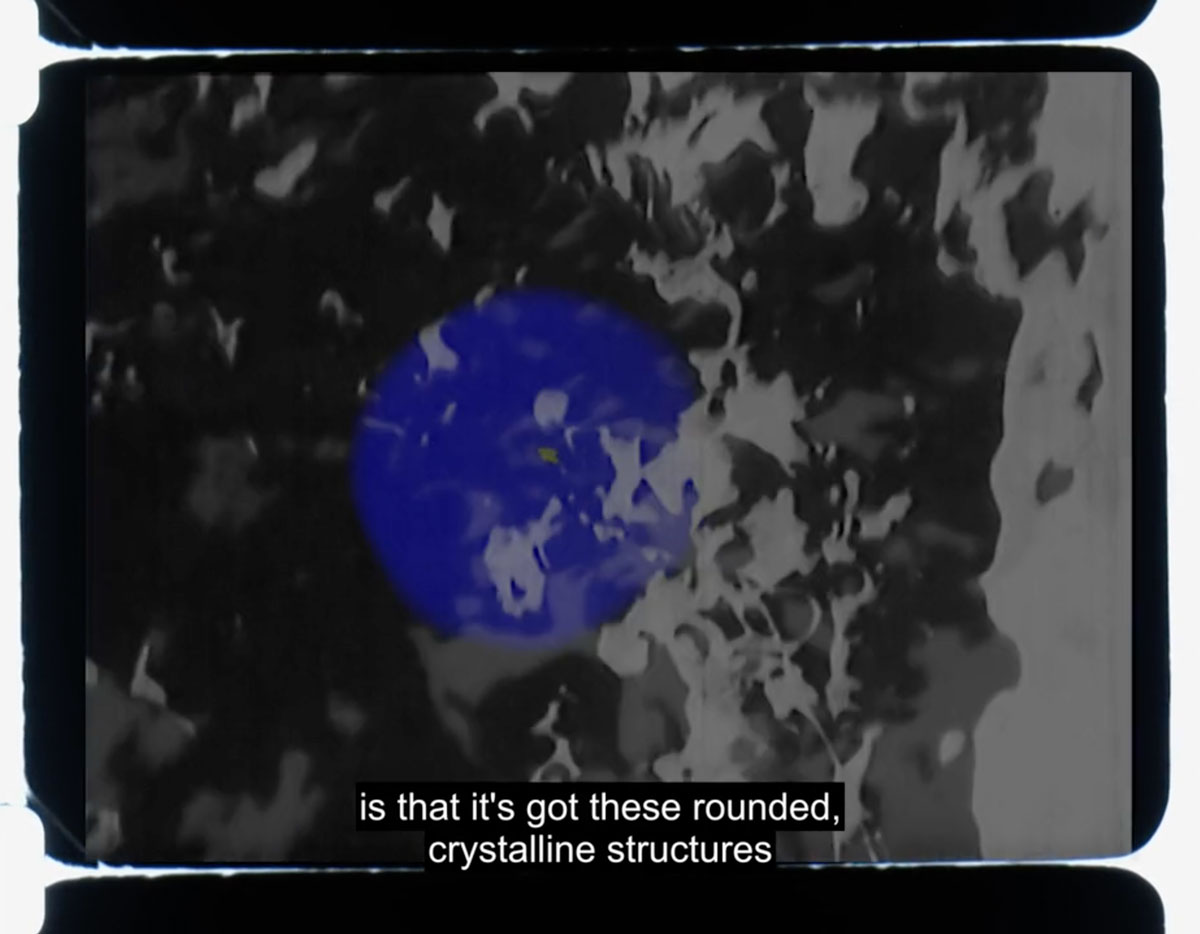

Caves are environments of extremities and liminality. Our senses shift and all that we used to rely on becomes obstructed by overwhelming darkness. Species evolve and adapt to dark environments, losing their sight all together over the ages. This is the case for the cave shrimp niphargus kochianus, found in Pen Park Hole. The site is the only place where both this species and a similar one, niphargus fontanus, are known to exist. This is a key reason why Pen Park Hole is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. These crustaceans are tiny – merely a few millimetres long – white, like blanched prawns, have no eyes and some species of cave shrimp (there are four in Britain altogether) can survive for several months without eating.

I have an affinity with these cave shrimps: their precarity and dark, niche environments, in a weird way, echo my way of working and use of photochemical processes in a digital epoch. The 16mm film was hand processed by myself in a small dark room in Bristol. Self-processing these films I access an autodidacticism on image-making and cherish the serendipitous mishaps of the alchemical process of water, silver, light and chemistry. It is a process you can do alone, with no need to rely on large crews and equipment. Contemporary photochemical filmmakers such as James Holcombe or Karel Doing have transformed sheds and garages into DIY dark rooms for this effect. I have also adapted to using outdated cheaper film socks, old broken cameras, and only making ‘art’ when I am not confined by the process of getting by. My work is disseminated through an ecology of niche environments: screenings of experimental & expanded film, artist-run film labs and improv gigs, that all take place within the dark.

Hence, the returning question of this work: how do we come to know an environment? The multiplicity of sensory inputs/histories (geological, social, economic, personal) and some of those ways of seeing are dependent on how we interface with, or process, a place. My way of processing is through repetition, by printing or repeating frames, as a way to analyse textures and the layering of surfaces. This visual investigation is akin to what experimental film researcher, Kim Knowles, terms ‘aesthetics of contact’:

it is precisely through the attention to surfaces, namely the photochemical substrate that registers the indexical trace of a physical encounter, that materialist film opens up a language of perceptual complexity. This aesthetic of contact […] privileges the unseen through an emphasis on sensation—that which cannot be comprehended through vision alone, but which points to the politics of the encounter, the hand of the artist, the layers of time and the communicative spaces between physical phenomena.2

In Southmead, the cave remains unseen for many, but its presence is deeply felt, perhaps even tangibly so. Its sense of mystery, its pulsating darkness, are as inaccessible and as far away as the misunderstood caricaturised panorama of daily life that unfolds above it. Just as it is primarily touch that one would use to navigate the paths of Pen Park Hole, it is through contact that this film is made, be it physical with the contact printing of photochemical film, or through outreach with the people I encountered. The resulting work is an autoethnographic survey of my neighbourhood as I witnessed its evolution over time. By drawing attention to the hole, it gave me a chance to speak to my neighbours in a way that resonated wider than neighbourhood reputation or small talk and to talk about ideas of place beyond a human-centric view. To make images is a process of learning how to see and to understand how things fit within the world. It’s astounding that Britain’s largest hydrothermal cave is below one of Bristol’s poorest suburbs; both of which are wondrous unseen treasure.

References

[1] Urban Dictionary, 2021, Available at: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=meader [accessed 18/04/2021]

[2] Knowles, K. (2020). Experimental Film and Photochemical Practice, Palgrave Macmillian. p.42

Recent articles

Southern California is many things. Quite infamously, it is known as a landscape defined by the automobile, from the emergence and diffusion of the highway system to fast food burgers, and the suburbanization of the United States. Walking this place then, would seem not only inconvenient, but ill advised. In… Read more »

What is today known as ‘whistleblowing’ could once take the form of interacting with a threatening gaze carved into the city wall. It is the case of the ‘boche de Leon’ or ‘lion’s mouths’ disseminated by the old Venetian Republic throughout its territory to suppress illegal activities. Through a close… Read more »

As he navigates through the recurrent lockdowns of the pandemic, stranded between hitchiking and muggings, job hunting and separations, Fabio Valerio Tibollo rediscovers photography as a powerful coping mechanism. Recording everything that happened around him for one year straight, from attending momentous events to finding curiosity in shots of simple living,… Read more »