Weaving as embodied place. Reflections from enskillment in the Mariana Islands

Drawing on first-hand experiences from weaving workshops, interviews, collages and excerpts from raw fieldnotes recorded during a fieldwork on the island of Guam in the north Pacific, this contribution reflects on the physical practice of weaving and how each material embodies a unique place in CHamoru society. Author Alba Ferrándiz Gaudens moves beyond the definition of place as merely a physical space, instead considering how enskillment and embodiment function as places of cultural production: spaces for full-body engagement in practice and the fostering of community.

The world of our experience is, indeed, continually and endlessly coming into being around us as we weave.

If it has a surface, it is like the surface of the basket: it has no ‘inside’ or ‘outside.’

Mind is not above, nor nature below; rather, if we ask where mind is, it is in the weave of the surface itself.

And it is within this weave that our projects of making, whatever they may be, are formulated and come to fruition.

Only if we are capable of weaving, only then can we make

– Tim Ingold1

In 2024, I spent six months doing ethnographic research on the beautiful island of Guam in the Marianas archipelago in the north Pacific. This was part of my PhD research investigating the display, agency and circulation of objects, people and knowledge from the Mariana Islands to Spain.

While most of my research involved collections-based and archival research, I also wanted to experience what it would feel like to make some of the objects I researched in my own skin.

Soon after arriving in Guam in the month of November, I met CHamoru weaver and multidisciplinary artist Roquin Siongco at a local party in Mangilao, one of Guam’s northeastern villages that overlooks the white limestone cliffs that cover that side of the island. I had followed Roquin’s work for years and soon ventured to ask if it would be ok if I signed up to some of their weaving workshops. Like many CHamoru artists, they were absent from Guam for months, navigating the continual pull between the island and mainland US.

Finally, in March, I joined two of Roquin’s weaving workshops at Guam Green Growth Circular Economy Makerspace, a community-led workshop and shop in Chamorro Village, a cultural space in Hagåtña, the capital of Guam. Initially, my plan was to document my weaving process through photography and detailed fieldnotes that highlighted technique.

However, as I engaged in the craft, I decided to also record personal reflections on my own experience: now looking back at those notes, I’d like to share my insights into that journey and the lessons I learned about the deeper connections between practice and place. Moving beyond the conventional definition of place as a merely bounded, physical location, I suggest reconceptualising place as a dynamic field of cultural production, shaped not only by spatial coordinates but by the lived, embodied experiences of those who inhabit and move through it.

Tinifok CHamoru, or the art of weaving, has been integral to life in the Mariana Islands for centuries. CHamoru weavers have long used leaves to create items of vital importance for the sustainability of the community – an importance that is deeply connected to the inhabitants’ identity, as I will explore in this piece. During my time in Guam, I experimented with niyok (coconut), åkgak (pandanus) and nipa, three local materials that have been at the core of the CHamoru weaving practice for long before the arrival of Europeans. Each of these materials has a specific set of uses.

Nipa is primarily used for roof thatching. Niyok and åkgak, on the other hand, are highly versatile materials. Traditionally, niyok was used to weave baskets, atupat (slings), gueha (fans used to keep fires alive), corona (plaited crowns), tali’i (rope) and katupat (pouches used to contain the boiling rice). Åkgak was utilised in the production of guafak (mats), layak (canoe sails) and hats, among others. Today, both materials are woven into all sorts of decorations, jewelry and even clothing. In the words of Roquin: ‘innovation is the tradition itself.’

The first thing anyone needs to do before one can start weaving is harvest the leaves one will use. Sourcing leaves requires deep knowledge of the landscape to identify the unique places of Guam where each species – niyok, åkgak, and nipa – grows. Niyok and nipa are available around beach and jungle areas which often blend into each other. Guam’s shoreline is mostly formed of coral landscapes that mix with white sand, dotted with tall coconut and nipa trees.

Thick jungle vegetation that includes palm, ifit, breadfruit and pandanus trees, as well as tangled vines and tall swordgrass, emerges the moment one steps past the first row of coconut trees beyond the beach. Even though these areas cover most of the surface of the island, the growing presence of the rhino beetle – a bug that targets palm trees – in the island has greatly decimated the presence of plant species typically used for weaving.

In fact, weavers always complain about how sourcing coconut leaves is the hardest part of weaving, as one needs to navigate the depth of the jungle to get to the shore, and as finding good leaves that are not damaged by the beetle’s presence is hard nowadays.

In contrast, åkgak is a domesticated species that, according to Roquin and other weavers, only grows in people’s backyards and in lanchos or ranches, vast areas of carefully cultivated landscape where fruit trees mingle with open pasture, alive with the rhythms of planting, harvesting, and care passed down between families. Together, these species map a living connection between weaving and the diverse environments of the island, a map that is mentally stored in the minds of every weaver.

Two landscapes of Guam: the beach and the jungle. From the white sand shores lined with coconut trees to the dense, green limestone forests and tangled vines, Guam unfolds in two distinct yet intertwined landscapes. Together, they hold stories of CHamoru life, deeply interconnected to the practice of weaving as a means of sustenance and belonging.

CHamoru weavers cultivate a profound attachment to the leaves, approaching them with care, affection, and reverence. The hour-long labour that goes into harvesting, followed by the preparation of the leaves before any weaving begins, adds to the whole process, which overall can take from two weeks to a month.

Preparing åkgak, for example, is time-consuming and often makes children disregard this material. During one of the weaving workshops run by Roquin, they told us that, whereas with niyok you can pretty much weave straight away using fresh leaves, åkgak needs to be de-thorned, peeled, straightened, flattened, cut into pieces, dried and, if you want, dyed.

Learning how to weave also involves a connection between material, skill and place – understood as a place where culture is created and passed on. While knowledge is transmitted from the instructor verbally and visually, it is ultimately up to you to make. The process can be tedious at first and takes time to learn. Two days after arriving in Guam, I met weaver Maria ‘Lia’ Barcinas at a planning meeting for Guam’s delegation to the Festival of Pacific Arts (FestPac).

I told her I was interested in weaving and she told me that, on that same day, a weaving class would be happening at the University of Guam in Mangilao. While that weaving class was my first experience engaging with the practice, the drive to the university campus was the beginning of a longer-term relationship that resulted in my involvement in a series of weaving workshops organised by Lia.

During one of those, Lia mentioned that the initial attempts to weave are often slow and challenging. It is all about consistent practice: becoming familiar with the leaves, how they twist, and making sure the spine always faces upward. This is reflected in the following excerpt written immediately after that workshop, where we were learning how to weave a niyok basket:

You start weaving the leaves in pairs of two (so two leaves weave into the next two leaves). You pick the first leaf and put it under the first leaf of the second pair. Then the second leaf goes over the first leaves and under the second leave. You then pull but don’t want to make it very tight because you’re going to continue weaving (Guam Green Growth, Hagåtña. 7 March 2024).

The labour that goes into working with each individual material represents a unique place in CHamoru society, as different techniques, sets of skills and technologies of embodiment need to be deployed to complete different woven objects. The form of each weaving arises from the materialisation of people’s imagined ‘finished product’ through skilled and mechanical repetitions of patterns. This rhythm of production holds a cultural place in people’s minds, a cultural place that connects tradition and innovation simultaneously.

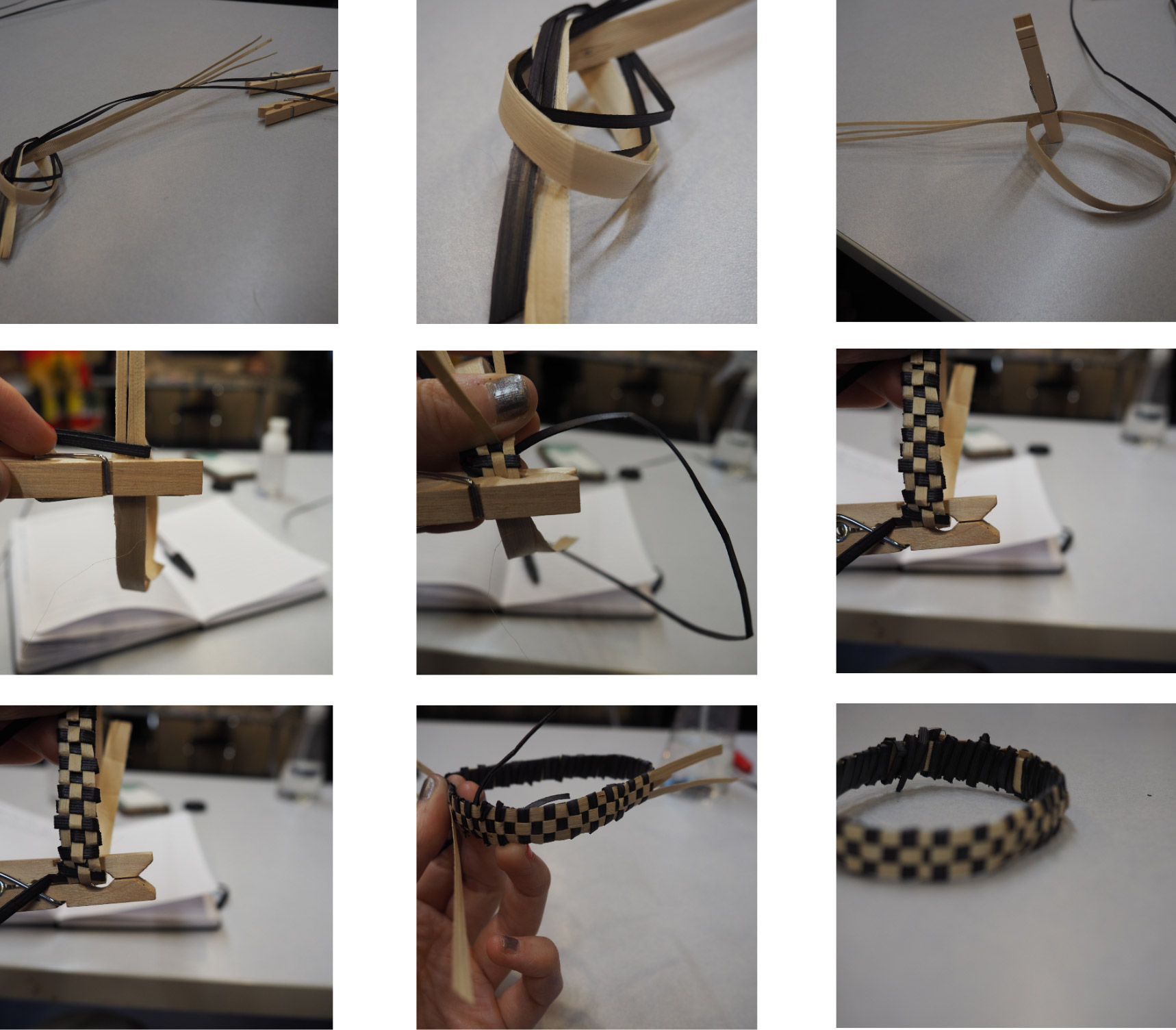

Collage documenting the process of creating a niyok (coconut) woven basket, including the final step of freezing the leaves to stop the excess moisture damaging the object. These photographs were taken during a workshop I attended on the island of Guam in March 2024.

Weaving with åkgak holds a different place in CHamoru society. While niyok weaving is widely extended in the islands, åkgak weaving is rare and many of the techniques used in the past have been lost. Not many åkgak teachers remain, and people like Roquin, who are invested in actively working to revive and transmit the practice of CHamoru weaving as a means to reclaim their Indigenous identity, have had to learn on their own through trial and error and by trying to reproduce woven objects kept in museums around the world. In my experience during Roquin’s åkgak weaving workshops, I learned that the best way to become skillful is by means of physically engaging with the material:

Although this weaving was technically more challenging and I certainly struggled with the start and finish, once I got the middle part it felt like a piece of cake. I just needed to concentrate to know which side I had to do next. The more I did it the easier it became, the faster I could do it, and the less I needed to think about it (weaving workshop, Guam Green Growth, Hagåtña. 21 March 2024).

Collage documenting the process of creating an åkgak (pandanus) woven pair of earrings. These photographs were taken during a workshop I attended on the island of Guam in March 2024.

But perhaps the most important part of learning to weave is doing it within a community of practice. Knowledge is transmitted orally, so being talked through and talking about the process is an essential part of the enskillment process. This was especially evident when I was taught how to weave a nipa roof thatch for the traditional seafaring class at the University of Guam.

The class takes place at the Pedro Santos Park in Piti, just south of Hagåtña, where the Master Navigator and teacher of the class Larry Raigetal was at the time leading the construction of a traditional Micronesian canoe house, built from wood, bamboo and nipa thatches, large enough to house a medium-sized outrigger canoe. To get to the canoe house, one needs to walk a narrow, man-made path along the jungle and next to the fence that marks the beginning of the Guam Power Plant.

The path emerges into a clearing that overlooks the ocean where the canoe house is located. Alternatively, one can cross the small river that separates Pedro Santos Park from the canoe house by walking over a fallen wood log that acts as a bridge. A few months before I arrived in the island, Typhoon Mawar – one of the strongest tropical disturbances that has hit the island in the last few years – destroyed the roof of the canoe house where the class is taught.

Mawar had a significant impact on the island’s landscape and livelihood, toppling countless trees that caused months-long power outages, tearing roofs off homes, damaging infrastructure and inflicting severe harm on reef areas due to intense flooding. Micronesian navigation is a way of knowing that brings together many interconnected skills and understandings, all of which must be learned before it can be applied successfully. In fact, Larry writes that ‘at the start, one must learn how to build a canoe house, which is fundamental aspect for passing on the rest of the knowledge’.2

The instructors of the traditional seafaring class wanted to honour this tradition given that the canoe house had lost its roof completely. In fact, when I first visited the canoe house, several men were in the process of assembling and tying wooden poles to reconstruct the internal structure of the roof.

The site felt empty and vast; the absence of the canoe house was deeply felt in the configuration of the landscape. All of the thatching had flown away from the previous roof, but some of the old thatches had fallen around the site and could be recovered and reused. As the class started, I immediately joined some of the students in making nipa thatches. They had more experience than me, and so they were teaching me, guiding me and chatting with me as we were practicing:

My thatch definitely looked a bit rough at first – the leaves were loose at the ends and the rope wasn’t always tight enough. I also misjudged how many leaves I’d need, so I had to pause to collect more, and later Melissa [one of the instructors] brought me additional ones. Mine didn’t look as tight or neat as some of the others, but as Vanessa pointed out, “That’s what it’s going to look like soon anyway,” gesturing toward the ones already on the roof – faded yellow and brown, soon to be covered by new thatching (Island Wisdom, Pedro Santos Park, Piti. 17 February 2024).

Photograph of my first finished nipa thatch. This was woven during the reconstruction of the canoe house at Pedro Santos Park in Piti, Guam in February 2024.

The process of weaving goes beyond the purely physical act of twisting, turning and tightening plant fibres. It is also used to signify the creation and strengthening of relationships – weaving relationships – and to refer to the stories that are shared between people as they partake in the act of weaving – weaving stories. In the following statement, Roquin reflects on this: “our ancestors wove sails that enabled them to cross oceans and settle the Mariana Islands around 3,500 years ago.

They also wove thatching for shelters and created mats for dreaming” (Interview, Sagan Kotturan CHamoru Cultural Center, Ypao, Guam. 26 March 2024). While the products of weaving serve essential roles in sustaining island life, the act of weaving itself is equally vital as it is often performed and narrated within communal settings. This intimate relationship between material, landscape, culture, community and skill creates a unique, flexible space that is embodied in the cultural practice of weaving. This is evident in CHamoru poet Arielle Taitano Lowe’s following verses:

Weaving Day (extract)

I look up between the leaves of the dokdok tree,

spaces between, silvers of sky.

Kahaukani [the wind of Mānoa Valley near Honolulu] rocks the branches

to an ebb and flow,

as I sit beside the Mānoa stream.

Holding the coconut fronds,

I observe the health of each leaf:

matured and bright yellow nuhot [stem of the coconut leaf],

deep, luscious, forest green.

I count,

Two…

four…

sixteen…

hold the knife and cut

into the base of the frond,

peel back the strip of leaves,

away from the stalk,

rest it on my lap.

Gather and roll the stripped base

into the brim of a hat.

Tie and tug.

I fold, and weave, and tug, each row.

Over, under, over, under.

I tighten, I fasten,

Until the hat is complete.

In the verses by Arielle Taitano, writing from the CHamoru diaspora in Hawai’i, is reflected the idea that place – and particularly the cultural place of being CHamoru– is made through the practice of weaving. Wherever they – or we – may go, this practice is carried within us. The muscle memory that is required to weave, which is acquired through physical and cultural enskillment, is deeply connected to people’s engagement with their island’s ecosystems and cultural ethos.

Cultural anthropologist Tim Ingold defines this as a taskscape: ‘just as the landscape is an array of related features, so – by analogy – the taskscape is an array of related activities… the taskscape is to labour what the landscape is to land’ he writes.3 In this view, place becomes not only where culture happens, but how it happens – through the full-body, embodied involvement of people in meaningful, sociocultural activity.

The experience of weaving in the Mariana Islands encapsulates this concept. The weavers’ (and my) embodied form of engagement with niyok, åkgak and nipa generated relational environments in which learning, doing and becoming are intertwined. Place, in this sense, is not understood as a static location, but somewhere –or something – that is continually made and remade through the rhythms of CHamoru community life, where skills are transmitted, identities are negotiated and belonging is cultivated.

‘Weaving,’ Roquin said at the beginning of every workshop and when I interviewed them, ‘is a conversation between people and their environment. Sometimes environments change and things change, but at the end of the day a lot of people go under-over-under, right? That really allowed me to home in on that.’

Roquin, who grew up in the diaspora in Tacoma, Washington, where many CHamorus live, knows very well what it means to carry the practice of weaving with them and use their own body as a medium between places and objects as they navigate the tensions between living in the diaspora and their homeland.

While there are technical steps to follow when weaving a specific item, it is ultimately the weaver’s sensitivity, emotion, and embodied skill that shape the outcome. Weaving is deeply rooted in feeling – not just as an emotion, but as a kind of place one enters. In a way, it becomes a practice of affect where emotional connection to the materials is essential, and where the weaver is part of a broader network of actors that go into the making of a woven object.

A weaver must feel for the leaves, care for them, touch them with intention and love – a phrase often repeated by CHamoru weavers. This emotional relationship creates a space – a felt place – where the weaver and the leaves meet, a place that could take place anywhere. I would like to end this reflection by bringing in one more quote from my fieldnotes:

Throughout the whole workshop they [Roquin] also repeated multiple times that weaving is in part experiential/emotional. “Don’t think, just weave,” they would say. Furthermore, weaving is a full body experience – you can do it outdoors, you can do it sitting down, standing. You can even use your thighs to hold the materials that you are going to be using later on. The location doesn’t matter, what really matters is the practice (14 March 2024).

Footnotes & references

[1] Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. New York: Routledge. p 348.

[2] Raigetal, L. (2022). ‘Revitalizing ‘Traditional’ Navigation Systems in the Contemporary Pacific’ in R. Tucker Jones and M. K. Matsuda (Eds.) The Cambridge History of the Pacific Ocean Volume 1: The Pacific Ocean to 1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 255

[3] Ingold, T. p 195.

Further reading:

Taitano Lowe, A. (2024). Ocean Mother. Mangilao, Guam: University of Guam Press.